High up on an auspicious hilltop next to Mt. Saraceno, the Italic Samnites built a large rural sanctuary in phases beginning in the fourth or fifth century BCE. Nobody knows with certainty what the Samnites called this sacred location. However, its modern name is Pietrabbondante, which is also the small mountain town in Molise, Italy. Sporadic excavations on the ancient sanctuary started in the 1800s and are ongoing today. With each new discovery, archaeologists are shedding light on the importance of Pietrabbondante, one of the last Samnite sanctuaries in existence.

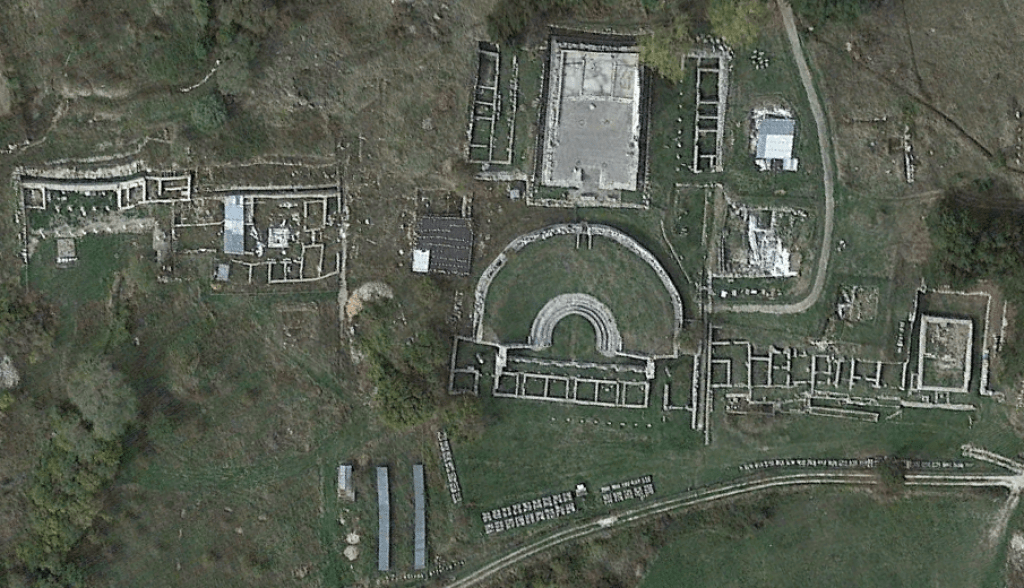

Excavations are still ongoing at the Samnite sanctuary at Pietrabbondante. Image: Google Earth.

Who Were the Samnites?

The Samnites, as the Romans called them, were likely an offshoot of the Sabines, an Indo-European Italic tribe that lived in the mountains of Italy since before the founding of Rome in the eighth century BCE. According to a few inscriptions, including one from Pietrabbondante, the Samnites referred to themselves as Safinim. Oscan was their spoken language, which was closely related to Latin.

Four distinct tribes formed within the Samnites: Pentri, Hirpini, Caudini, and Caraceni (Vigorito). However, during times of war, the groups would unify into a confederation or Samnite League. Toward the end of the last millennium BCE, the Pentri were the dominant tribe when the Samnite Wars with Rome started in 343 BCE. In fact, Pietrabbondante is a Pentri construction.

Pietrabbondante Archaeology

Among the numerous archaeological discoveries at the rural sanctuary are a large, ornate theater, temples, altars, inscriptions, various weapons, helmets, tabernae, and a house (the domus publica) with an elaborate portico.

Neolithic and Bronze Age Settlements of Gricignano

Temple B

Perhaps the most important feature of the sanctuary is a large late second century BCE temple built in conjunction with a Hellenistic theater. Temple B sits on a tall podium, or base, in alignment with the theater and is directly accessible from the theater.

Only the podium of Temple B still stands with two rectangular altars at its base. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

The Importance of Animal Sacrifices

Two massive stone altars rest on a level platform in front of the temple. Because of their location in the open, their presence provokes a sense that something immensely important occurred in front of an audience. On the left of the two blocks, there is another space where there may have been a third altar at one time.

According to Federica Fasano, an expert scholar on Pietrabbondante, priests made their blood sacrifices of animals to the gods on the altars. Because blood was important for the pacification of deities, deliberately cut channels in the rock allowed the blood to drain into the earth. In this ritual, the Samnites propitiated the gods, however, they also received omens by looking at the bowels of the animal (ECHO Molise).

One of the altars in front of Temple B. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

Temple B Architecture and Inscription

The architecture of Temple B reflects a Rome-Latium style with Greek and Etruscan features. In the front of the temple, a Corinthian colonnade held up a large porch. Inside, the area was divided into three sections with white mosaic floors. Two of the areas kept the treasures that worshippers had brought as offerings to their gods.

The Ancient History of Pompeii

Interestingly, an inscription is still visible today on the left wall of the temple podium. It bears the name of the person – G. Staatis L. Klar – who contracted and funded at least part of the building (La Regina). Additionally, the wall in the back of the temple reveals a carving of a phallus. This would have served as a type of talisman for good luck and fertility.

Look closely to see the inscription on Temple B. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

Hellenistic Theater

Just down the steps from Temple B, commoners could enter the upper section of the theater characterized by wooden seating. Today, all that is visible in this upper section is grass, however, post holes evidenced the ancient seating arrangement. In contrast, upper-class elites sat in the lower area closest to the stage on stone seats.

This Hellenistic theater, along with Temple B, was central to all major functions. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

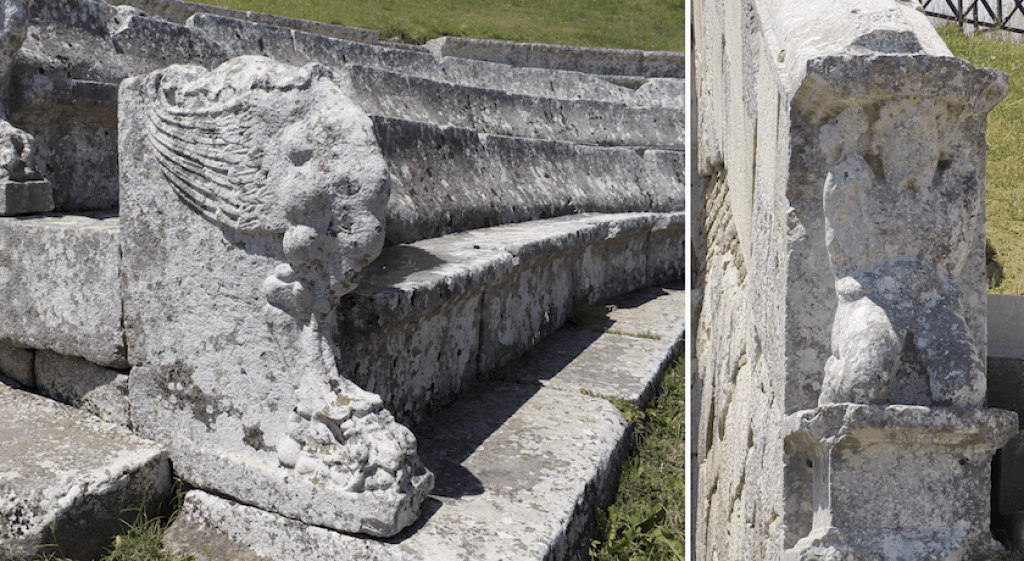

Additionally, chimeric creatures resembling lion-griffins detail the armrests at the end of each stone row, while Telemones or Atlases hold up the walls connecting the arches to the seating.

Catacombs of San Gennaro: Ancient Site of Worship and Burial

Griffins decorate the ends of the stone seating L). Telemon holding up the wall R). Photo: Historic Mysteries.

The theater takes a horse-shoe shape with two main entrances on the sides. Arches originally built without mortar frame the doorways. Behind the stage, a series of stone rooms served as dressing rooms. From the rooms, performers and speakers at assemblies could enter via one of three doors directly onto the stage.

The Temple-Theater Complex

Temple B and the theater were physically connected by a short walkway. This connection is a reflection of the interconnectedness of the Samnite religion with every aspect of their lives: political, military, and personal. The theater hosted various events, however, perhaps celebrations of seasonal changes also occurred here (Fasano).

Entry to the theater. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

The temple overlooked the political assemblies and events in the theater and, in this way, represents the power the Samnites placed in their gods as overseers of their lives and deliverers of good and bad. Together, Temple B and the theater constitute the most important structural complex to serve out the purpose of the site as a place of cult rituals and political gathering and ceremony.

First Phase of the Sanctuary

Under the theater and temple B complex, archaeologists found evidence of an older temple and sanctuary. This first phase likely dates back to the fourth century BCE, as evidenced by the rich deposits of weapons. The reason for this cache probably pertains to the Samnite Wars with Rome, which began in the fourth century. However, weapon styles were not just Roman. There were weapons from other groups as well.

During this time, it was a common practice for the victors to take the weapons from their conquests. However, this “war booty” served a very important purpose for the Samnites. Apparently, they used the old sanctuary at Pietrabbondante to offer the weapons up as trophies to the goddess Victoria (patron of victory in war). This is based on an Oscan inscription on a votive dedicated to her (La Regina). However, in 217 BCE, the Carthaginian Hannibal sacked the old sanctuary.

Domus Publica and Portico

Archaeologists uncovered an unusual structure connected to the Temple B-theater complex on its south-west side. Apparently, it dates to the same period as the complex. This Domus Publica, as the name suggests, contained living quarters and also a ceremonial hall used for special gatherings and banquets for priests and magistrates.

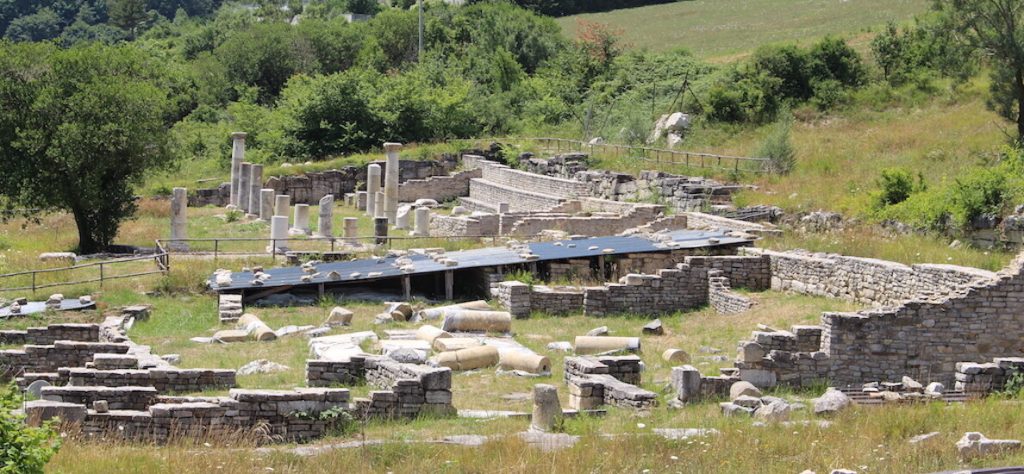

The domus publica is still undergoing archaeological excavations. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

Behind the rooms, a long portico with nine columns at its front contained an altar and housed votive offerings. These came from those in need of a blessing or desiring to give thanks to a god. Especially in times of hardship, offerings played a large role in the religions of ancient Italy. According to Federica Fasano, Samnite votives could take the form of various things but body parts, phalluses, female genitalia, and statues were common. Not vulgar in their meanings, the genitalia were symbols of fertility and fortune.

Also within the portico, researchers discovered an intriguing inscription dedicated to the goddess Ops Consiva, an ancient Sabine deity. She was the mythological wife of Saturn and was a goddess of fertility, abundance, and crops. (Story:368).

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Adriano La Regina”]Inscriptions were found that mention the cult of Honos, the divine personification of military and civil honour. . . . This group of abstract deities, Plenty [Abundance], Honour and Victory provide a picture of the ideological characteristics of the state cult practiced by the Pentrian Samnites in the monumental sanctuary of Pietrabbondante.[/blockquote]

Temple A

A smaller temple sits in the north-east of the sanctuary and dates back to the beginning of the second century BCE. This is one of the oldest archaeological discoveries of the Samnite sanctuary from excavations in the 1800s. Although most of Temple A had crumbled away, scientists have restored the podium that it once sat on to show the original size of the temple.

Not much remains of Temple A. The podium wall is a reconstruction. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

A number of weapons and at least two notable Oscan inscriptions were found here. One of them says safinim sak [araklum,] ‘the cult place of the Safin people,’ (Farney et al. 2017) attesting to the ethnic identification of the site as belonging to the Samnites. Another inscription names its dedicator, Gn. Staiis Stafidins, who was a high ranking politician.

Temple L

The tabernae (shops) in front of Temple A appears to be an older phase of the sanctuary. Additionally, ground surveys revealed an additional older temple, Temple L, about 100 meters east of Temple A. According to La Regina, Temple L probably dates to the third century BCE. During excavations in 2011, scientists found a roof tile dedicated to the Venus Erycina. This possibly suggests that the temple may have been dedicated to her. Additionally, weapons from the fourth century BCE had decorated the temple, attesting to the ritual offering of spoils of war in thanks to the gods. (Fasti).

The Etruscan Pyramid of Bomarzo

Temple L was unlike other Samnite buildings in the Pietrabbondante sanctuary. Although it contained molding that could classify it as an Ionic temple, it did not have the characteristic podium. It was almost completely square and surrounded by walls, except for a doorway in the middle of the building at its front. It also had characteristics of Etruscan architecture with an internal side room or wings (an alae). Regina proposes that Temple L stood as a treasury for the collection of tithes and taxes. Indeed, excavations unearthed a chest of bronze and silver coins sunken into the ground inside the building. Additionally, its architecture is more suggestive of a high-security vault than a temple.

The Last Days of the Samnites

Pietrabbondante rose up in size and stature among the Samnites during the series of wars with Rome. Experts believe the site reflects their ethnic and cultural resilience and ongoing fight. Although their architecture and building plans may have included Hellenistic and Roman styles, some scholars caution us not to believe that the Samnites wanted to become Roman or that they were in any way giving up their ethnic identity. In fact, there is a preponderance of the evidence that suggests otherwise. Ultimately, the site was a sacred place for Samnites to find religious and political fellowship, to boost military morale, to worship together, to celebrate various festivities, and to appeal to and thank the gods and goddesses.

After the Social War from 91-88 BCE, Rome conquered most of the Italian peninsula and sealed the fate of the Samnites. Thus, the Samnites halted all construction in progress at Pietrabbondante, and the people who once called themselves Safinim abandoned their beautiful sanctuary for good and faded away into history.

For more information or to provide much needed financial support for ongoing archaeological excavations at the Samnite sanctuary, please go to their official website INASA.

References:

-ECHO Molise. “Samnites.”

-Farney, Gary D., and Guy Jolyon Bradley. The Peoples of Ancient Italy. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018.

-Fasano, Federica. ME.MO Cantieri Culturali.

–La Regina, Adriano. “Excavations.” Fasti Online.

-Story, John. “Roman Deities.” Scribd.

-Vigorito, Michael. “Ancient Times First Millenium BC.” Vigorito Genealogy History – References.