Around the 8th century BCE, the Euboean Greeks founded the settlement of Cumae close to Lake Avernus just west of Naples, Italy. The lake is an extinct crater that sits in an enormous caldera called the Phlegraean Fields. Abundant fumaroles and geothermal hot springs dot this dramatically volcanic zone and inspired dark religious beliefs. Avernus Lake became an important place of pagan ritual and worship and is famous for its rich mythology describing chthonic gods, oracles, and sacrifices. Virgil made it famous in the Aeneid. But it was really the Greeks who first associated it with infernal elements. For them, it was a doorway to the underworld of Hades where all dead souls dwelled.

About the Lake

Lying close to the Mediterranean coast, Lake Avernus has a circumference of nearly two miles and reaches a depth of 213 feet. Green slopes, once thick with cypress woods, rise from their base up to a height of 360 feet. Views from the rim of the volcano include the Tyrrhenian sea with its islands of Capri and Ischia. The name Avernus (Latin) stems from Aornos, meaning without birds in Greek, for the belief that toxic gases rose from the lake and kept all the birds away.

Lake Avernus Mythology

Ancient Greeks and Romans associated all of nature with their pantheons of gods. Thunder and lightning meant that Zeus was on a rampage. Rough, deadly seas and earthquakes resulted from an angry Poseidon. Therefore, it seems natural that a region with fumaroles and hellish gas emissions from the hot ground could be interpreted as a portal to Hades.

In fact, the word inferno — the Italian word for underworld or hell — is related to Averno, the Italian form of Avernus. At one time, people living around the lake believed that it was bottomless and called it the Styx (Tesoriero:221). Running between Earth and the Underworld, the Styx carried the departed to Hades. So strong was this belief, that residents refused to drink from the stream nearby that ran underground out to the sea.

What were the various versions of the Narcissus myth?

Many people believe that Homer (c. 850 BCE) wrote about Lake Avernus. Although he did not name the exact place, his geographic descriptions in the Odyssey have some similarities to the area. In the story, Odysseus holds a meeting with the ghosts of the dead at a temple on the shores of a lake at the entrance to Hades. Homer also wrote about the Cimmerians who dwell in the subterranean caves around a lake and never see the light of day. (Strabo).

Virgil Immortalizes Avernus

Like Homer, the author and poet Virgil blended Greek mythology with real geographical areas in Aeneas’ adventures in the Aeneid. However, unlike the former poet, Virgil specifically names Avernus. The plot involves Aeneas who flees the war in Troy and conquers the Latins to found Rome on the Italian Peninsula. Avernus enters in Book Six when Aeneas seeks out the prophetess sibyl at the Greek settlement of Cumae for her help. Aeneas wishes to descend into the underworld to speak to his father who died on the sea voyage from Troy. In an ecstatic trance, the sibyl channels the god Apollo to foretell Aeneas’ great future and gives him tasks that he must accomplish before he can enter Hades.

Did the Trojan War really happen?

One of the tasks requires Aeneas to collect a golden leaf in the woods of Avernus to offer as a gift to Proserpina, the queen of Hades. After finding the leaf, the Sibyl leads Aeneas to a deep cave with a wide entrance near the lake where they sacrifice four young bulls. The blood is collected in bowls, and the entrails are placed on the fire at the altar built in honor of Pluto (god of the dead). After a night of intense witchcraft, invocations of gods, and more sacrifices, they enter into the wide cave to descend into Hades.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Virgil”]“Straightway they find a cave profound, of entrance gaping wide,

O’erhung with rock, in gloom of sheltering grove,

Near the dark waters of a lake, whereby

No bird might ever pass with scathless wing,

So dire an exhalation is breathed out

From that dark deep of death to upper air:—

Hence, in the Grecian tongue, Aornos called.”[/blockquote]

The Oracle of the Cumaean Sibyl

Aside from the stuff of poems and epic tales, seer-healers and divination were very real aspects of early Greek, pre-Roman, and Roman societies. In fact, this is true of most early cultures. Thus, oracles were common and undoubtedly existed around Lake Avernus. The term oracle usually refers to a seer or a place where a seer prophecies. The Cumaean Sibyl was one such oracle who was probably a real priestess living in Cumae at one time. However, there were many seers around the ancient world, the most famous of which was Pythia at Delphi, Greece.

History of the World Renown Oracle of Delphi

Known for their intoxicated trances and sometimes wild prophetic frenzies, prophetesses served as intermediaries between humans and the gods. The Cumaean Sibyl, for example, channeled the voice and will of Apollo, the god of prophecy and sunlight.

Where is Sibyl’s Cave?

The actual temple or cave where the priestess lived is still uncertain. However, in 1932 the Italian archaeologist Amadeo Maiuri excavated a tunnel in the hillside at Cumae. He believed it to be the Sibyl’s Cave with the “Seat of the Sibyl” at the back of a 140 m. long gallery where a chamber opens into three niches. On the left of the chamber, a stone bench lies outside a niche that contains yet three smaller nooks.

Interestingly, the chamber at the end of the cave resonates with amazing acoustics and a circular opening in the roof of the tunnel leads directly up to the floor of the Temple of Apollo. Whether or not this was an original feature or was a later addition is uncertain.

Some experts believe the architecture of the tunnel and chamber niches appear funerary in nature. However, “recent studies attribute to the structure a defensive function” (Iannace) that probably occurred in Augustus’ time. In their paper, The Acoustic of Cumaean Sibyl, Iannace and Berardi speculate that the cave was several things through the years: Sibyl’s Cave during the Greek period, possibly a defensive structure during the Roman occupation, and a Christian graveyard.

The Oracle of the Dead

In addition to the Cumaean Sibyl, old stories of another oracle exist. In his book Geography, Strabo (63 BCE-23 CE) wrote that other writers made claims about an Oracle of the Dead living at Avernus. Some people believe that the site of this oracle is in Baiae, just next to the lake on the coast. In the 1960s, the amateur explorer Dr. Robert Paget was searching for Sibyl’s Cave when he found a sulfuric, hot opening amongst the ruins of the ancient Roman baths.

A complex of narrow but tall tunnels shocked Paget. About 140 feet underground and 600 feet from the entrance of the cave, he found a river with flowing hot water. Some propose that this probably fed the huge Roman thermal bath resort directly above. However, Paget and others believe that this was part of an elaborate ritual in which perhaps a priestess led people on a physical journey down the river Styx to the imagined underworld. (Dash). The Oracle of the Dead could then channel loved ones who had passed on.

Gods and Sacrifice at Lake Avernus

Naturally, any underworld or even any body of water involved the Greek and Roman gods. This meant that Lake Avernus was once a highly sacred place of cult ritual. “Sacrifices were regularly made here to the chthonic deities that lurked beneath the murky surface” (Dunford). Not only did Virgil write a detailed description of sacrifices before Aeneas entered the cave to the underworld. Hannibal actually visited the lake in 214 BCE, where many believe he prayed and made sacrifices and offerings to the gods. He may have been seeking their favor, as he had high hopes for conquering the whole region and, in fact, subsequently attacked Cumae unsuccessfully. (Smith).

[blockquote align=”none” author=”William Smith”]”Avernus was also regarded as a divine being; for Servius speaks of a statue of Avernus, which perspired during the storm after the union of the Avernian and Lucrinian lakes, and to which expiatory sacrifices were offered.”[/blockquote]

Temple and Bathhouse in Ruins

Ruins of a Roman building still stand on the southeast bank. Unfortunately, only the dome is now visible as it lies under much sediment. Most people know this structure as the Temple of Apollo. However, many scholars dispute this. Others say that it was in honor of Proserpina, Pluto, Hecate, or that it was simply a Roman bathhouse and nothing more. Pietro Micheletti who authored History of the Monuments of the Realm of Two Sicilies believes that it was a temple honoring the deity of the lake, also called Avernus.

What explains the hundreds of skeletons in India’s Roopkund Lake?

The circular building came into existence at the time of Agrippa or shortly thereafter, around the end of the first century BCE. It did serve as thermal baths for the increasing population and Roman workers at the lake. However, the gods were always involved in everything, and features at Roman baths were commonly dedicated to certain gods. The real question is, what existed at this spot before the bathhouse? Although some experts speculate that earlier altars probably existed here, no one is certain.

Roman Use of the Crater Lake

An unfortunate end to the mythological beliefs and dark superstitions at Lago d’Averno came in the last century BCE. At this time, Sextus Pompeius was launching attacks of strategic shipping ports in his quest for control of the Mediterranean trade. Thus, defeating him became a huge priority for Augustus.

Mono Lake and its Sea of Natural Mysteries

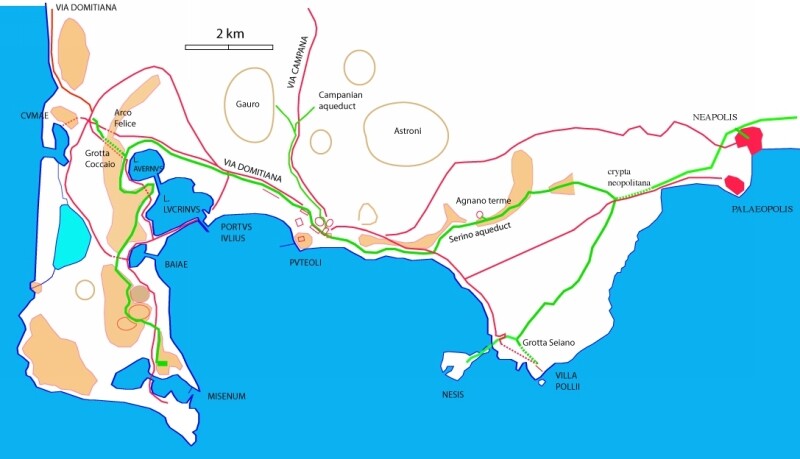

Roman general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa undertook a major engineering project when in 37 BCE he turned Avernus into a hidden naval base. First, he built a discreet man-made canal to connect Avernus to the adjacent Lake Lucrino. Another hidden channel joined Lake Lucrino to the sea. Then in honor of Julius Caesar, they called their new base Portus Julius. (Tesoriero).

At the same time, Agrippa hired Lucius Cocceius Auctus to build a secret tunnel. This gallery cuts through the mountain connecting Lake Avernus to Cumae. Through Cocceio’s Cave, they hauled supplies to the lake for the construction of a fleet of ships that would attack Pompeius by surprise. This arrangement was ingenious, as Avernus was a secure location that could not be seen from the sea.

The End of the Avernian Underworld

After Pompeius’s defeat, the Romans abandoned Portus Julius due to silt deposits that had collected on the lakebed. This made navigation difficult. Even before the construction of Portus Julius, Caesar had already cleared the trees around Avernus turning the land into farms to support the growing Roman resort town of Baiae. This, in addition to the larger naval engineering projects, changed the atmosphere of the lake into a much brighter, happier place free of ghosts and oracles. By then, there were no emissions of toxic gases — at least not from the lake itself — if they ever existed at all. In one fell swoop, the introduction of the Roman Republic into the area displaced all that was mysterious and hellish around what became Lago d’Averno.

Avernus Today

Now life abounds at Lake Avernus as it peacefully lies in the modern town of Pozzuoli. There is no longer any evidence of the dark underworld, aside from occasional wafts of sulfur from the Solfatara crater a few miles away. With plentiful vineyards, orchards, fish, birds, and a few restaurants, the crater lake has become a destination for tourists and locals out for a run or a quiet walk.

Feathered residents include both ducks and geese, and a slew of birds fly overhead, including crows, seagulls, and sometimes small bats that dwell in Cocceio’s Cave. A pleasant footpath encircles the shore of the lake. Pedestrians can walk to the temple ruins on its east end and the Grotta di Cocceio to the north. Though no longer believed to be the entrance to Hades, the stunning beauty of the crater lake makes this place no less magical.

Additional References:

Micheletti, Pietro, and Scipione Volpicella. Storia Dei Monumenti Del Reame Delle Due Sicilie. Napoli: Del Fibreno, 1847.

P. Vergilius Maro, Theodore C. Williams, Ed. P. Vergilius Maro, Aeneid, Book 6, line 183.

William Smith Perseus Tufts