The story of Jesse Harding Pomeroy: a boy convicted of being a murderer at age 14, who at that point had already been conducting his violent behavior for years.

In 1874 in Massachusetts, United States, Jesse Pomeroy became the youngest person ever to be convicted of first-degree murder. He was 14 years old, but his crimes were horrific, violent, vicious, and bloody. He spent the next 58 years in prison before dying in 1932 aged 72.

Jesse grew up as an impoverished youth of Charlestown, Massachusetts. He was born with a birth defect, an eye that was covered in a thick white film. Jesse was bullied heavily in school and was likely beaten at home. This is, however, no excuse for the crimes he would commit and the character he became.

Childhood

Jesse Pomeroy was born to Thomas J. Pomeroy and Ruth Ann Snowman in 1859, the second of two children. His brother was two years older and called Charles Jefferson.

It has been claimed that Jesse’s father Thomas was a veteran of the US civil war. He worked in the Naval Yard and likely beat his two children. Whilst this has been disputed, it is not out of the realms of possibility.

Reportedly, Thomas beat Jesse with a horsewhip regularly and forced him to strip naked. Equally, to add to Jesse’s woes he developed a serious case of pneumonia in 1871, that did not leave him well.

His crimes and misdemeanors started early. At the age of 5, Jesse’s neighbor claimed that Jesse had stabbed a cat to death and threw it in the river. One of his teachers said that throughout his time at school, Jesse was “Peculiar, intractable, not bad, but difficult to understand”.

One of his favorite pastimes was to read frontier life novels and he relished in the savagery of that lifestyle. Due to his birth defect, other children shunned him, and he retreated into isolation.

Criminal Activity

Around 1871, Charlestown newspapers began to circulate stories of children claiming that they had been beaten and sexually assaulted by a larger and older boy. They had been lured down away from main streets with the promise of sweets before being violated.

Some were even disfigured by a knife and pins. The targeted areas were often the face and genitals. The description of this boy was published in the Boston Globe with titles like “The Boy Torturer” and “The Red Devil”.

Jesse’s mother, Ruth, and likely many others in Charlestown began to recognize this description as relating to Jesse. She, quietly, moved the family to south Boston in an attempt to quell the rumors and curb this behavior from Jesse. Unfortunately, this was not successful.

In August 1872, a boy was found tortured and left on a beach. Another was found beaten, raped, and tied to a telephone post. Another victim told the local authorities that he had been assaulted by an older boy with a marbleized eye.

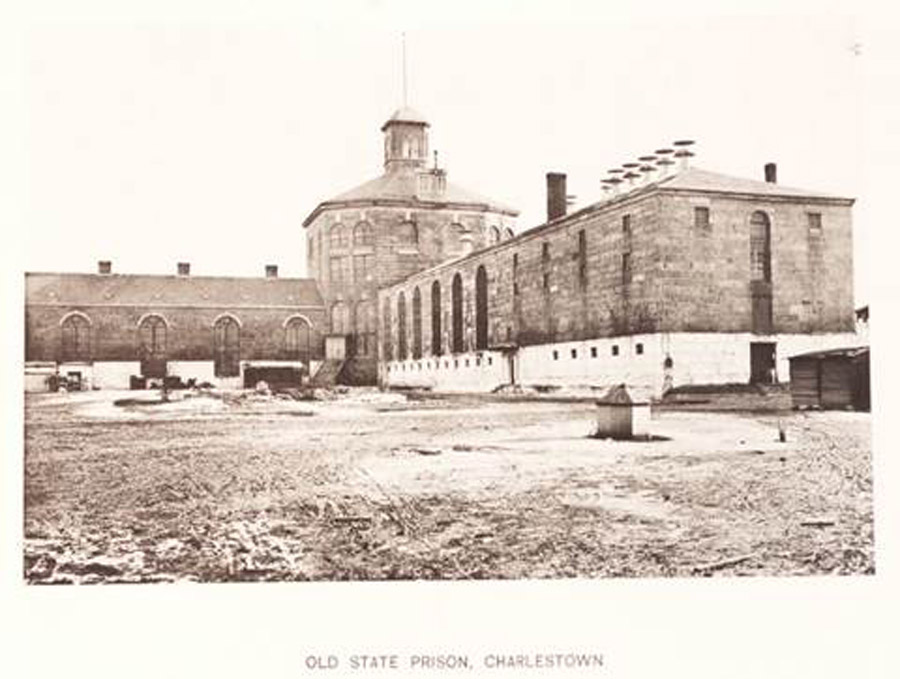

This distinctive feature led the police to the door of Jesse Pomeroy. He was taken to the State Reform School in Westborough. He was supposed to serve six years, though Ruth managed to get him out in a matter of months.

Capture

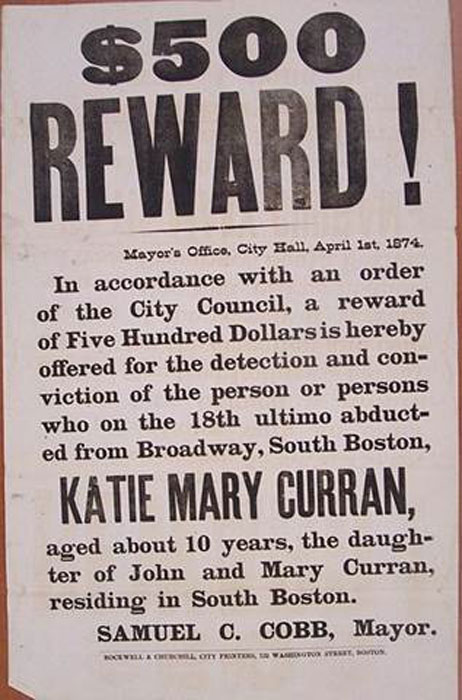

Despite his troubles with the law and having already been caught once before, Jesse remained undeterred from his course of action. He had been released from the State Reform School for only a month when ten-year-old Katie Curran disappeared. She was last seen in Ruth Pomeroy’s shop.

To add to this concern, Jesse was known to work there in his spare time. He was thoroughly questioned, and the shop was searched, but no sign of Katie was found.

Five weeks passed and no evidence was found. That was until the body of Horace Millen, aged four years old, was found on the beach. He was discovered by a couple of boys out collecting for clams on the beach, who stumbled across Horace’s body in a ditch.

- 5 Most Brutal Serial Killers in Recent History

- Papin Sisters: Shocking Housemaids’ Crime That Shook France

His body had been mutilated with his genitals almost entirely cut off. Stab wounds in the shapes of ‘X’s had been cut across his body. The body had also been set on fire.

The police were alerted to Horace’s body and found the footprints of a boy at the site. With their suspicion already aroused, they paid another visit to Jesse Pomeroy. He was found covered in blood and with scratches on his skin, presumed to be Horace’s defense marks. They matched his boots to those found at the scene and uncovered a bloody knife on his person.

Confession

The police immediately brought Jesse in and began to question him. Whilst they had accumulated significant physical evidence, they still required a confession.

In the event this proved easier than they thought. Under questioning, Jesse not only admitted to the murder of Horace, claiming “I suppose I did,” but also to the murder of 27 others. This figure was never confirmed, although the confession did help police find the remains of Katie Curran buried close to his mother’s shop.

Jesse was taken to trial and found guilty of both murders of Horace Millen and Katie Curran. Originally, the sentence was death. However, due to his age, Jesse was shown some leniency and allowed to stay alive but in exchange for life imprisonment. His defense attorney had attempted to push through an insanity plea, but this was rejected.

During this trial moralists tried using this episode as an example of moral standards falling. They blamed the “Dime Novels” that showed garish stories of blood and gore. However, this attempt to create a moral panic was discounted as Jesse had never read the novels.

Death

Jesse’s stint in prison was a long and solitary one, only permitted to eat and exercise on his own. He was allowed reading materials and utilized this luxury. But with little else to occupy him, his mind eventually turned to escape.

Jesse made several escape attempts, including an attempt to dig his way out, and rerouting a gas pipe to explode his cell door. All failed. It was not until 1917, 41 years after his imprisonment that he was allowed to socialize with other inmates.

In 1929, Jesse was taken to Bridgewater prison farm where, elderly and alone, he died three years later.

Top Image: Jesse Pomeroy. Source: Unknown Author / Public Domain.

By Kurt Readman