The crusades were a masterstroke for the Catholic Church. When Pope Urban II proclaimed in 1095 that mortal sin could be erased by a religious campaign to recover the Holy Land and Jerusalem, he cemented his authority and started a movement which would change the face of the world forever.

The opportunists, the ambitious and the truly devout took the cross in their tens of thousands, carving a bloody swathe into the Muslim kingdoms for centuries. But not all crusades were against this obvious foe, and as the years passed, more creative proclamations from subsequent Popes led to other targets being found.

In the end, you could become a crusader having travelled no further than southern France. The Albigensian Crusade was called by Pope Innocent III against the Cathari, gnostic Christians also known as the Cathars. From the first hostilities in 1209, it led to twenty years of war.

This crusade was much more divisive than the original concept of war against a distant, alien enemy. Now, the staunch Catholic nobles in northern France fought those found in the south of France who tolerated and supported the Cathars.

The crusade itself did not eliminate Catharism but allowed the French king to establish his authority over the south. In the process however this crusade set a dangerous precedent for attacking fellow Christians. But where do the origins lie and how did the crusade end?

Origins

By the middle of the 12th-century, control of Jerusalem and the Holy Land was no longer the sole goal of the crusaders. Crusading had become a special class of war called by the Pope against those that were designated enemies of the faith. The crusaders targeted pagans and Muslims continuously, but also began to aim for heretics in Christendom.

During the late 12th century and early 13th century, the most powerful and vibrant heresy in Europe was Catharism. Centered around the Languedoc region and the city of Albi in southern France, the religious movement was tolerated by the local aristocracy and allowed to thrive.

The Roman Catholic Church, wary of a center of Christian teaching over which they had limited control, had attempted for years to cut out the heresy from southern France. in this they were often thwarted by the Barons of the area such as Raymond VI of Toulouse. Things came to a head in 1208, when the Pope called a crusade against Raymond and the Cathars.

The Heresy of Mysticism

Catharism held that the universe was a battleground between good, which was spirit, and evil, which was matter. Human beings were believed to be spirits trapped in physical bodies. Their leaders lived with great austerity, remained chaste, and were vegetarian, avoiding all foods that came from sexual union.

- Joan of Arc: Divinely Inspired or Mentally Ill?

- Asherah: did the God of the Hebrew Bible have a Wife?

This abstinence was of no concern for the Catholic Church, but the teachings were more problematic. Cathar doctrines of creation had led them to rewrite the biblical story, rejecting the doctrine of the Old Testament.

Cathars believed that Jesus was merely an angel, and his human sufferings and death were an illusion. These beliefs struck at the roots of orthodox Christianity and the political power base of Christendom, and a military response from the Church looked increasingly likely as the movement grew.

The Crusade

Fervor for the initial crusade was immensely popular in northern France. It allowed the pious warriors to win a remission from punishment in the afterlife without risking travel to the dangerous middle east, and they did not have to serve for as long. A huge army was raised and marched into southern France.

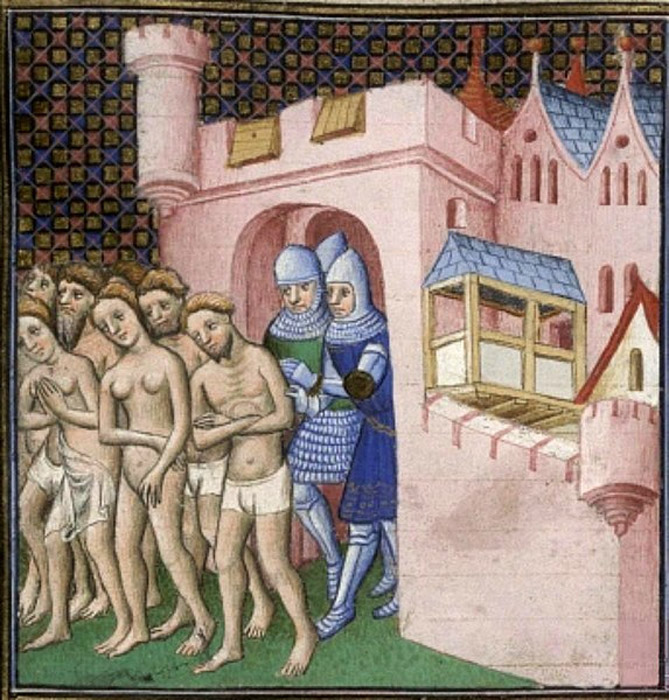

One of the first places to be captured by the Crusaders was Beziers in the heart of the Cathar territory. The religious fury was as extreme as any attack on Jerusalem, and unconcerned about collateral damage: it was said that the papal legate accompanying the Crusading army told them to “kill them all, God will know his own.”

The crusaders duly massacred the entire population of Beziers. From there much of the territory of the Albigensians was surrendered, the exception being the castle city of Carcassonne which held out for a couple more months.

The command of the Crusade passed to Simon de Montfort, a French nobleman who had made a name for himself during the Fourth Crusade between the years 1202-1204. The next battle focused on the area around Lastours and the castle of Cabaret.

The crusaders initially attacked in December 1209 but were repulsed. The fighting then largely stopped as nobles returned home during the winter, being replaced with fresh crusaders eager to earn remit for their sins the following year.

After weeks of siege, Simon slowly began to gain the upper hand, capturing cities and towns around southern France. He spent much of his time attempting to convert Cathars but was ultimately unsuccessful. Those who refused were burned at the stake.

- The Holy Foreskin: Where is the Last Piece of the Body of Christ?

- Why was the Infancy Gospel of Thomas Excluded from the Bible?

The Albigensian Crusade continued for many years, fueled by new recruits replenishing the forces that returned home. New recruits would arrive each spring, returning home at the end of summer leaving Simon with a skeleton force to protect his gains over winter.

The End of the Crusade

By 1215, when the Catholic leaders met at the Fourth Lateran Council, Simon had captured most of the region. Despite Raymond VI’s protests, the council granted all of the lands to Simon, but also rescinded the crusade remit so that they could encourage a new crusade to the east.

Only a few short years later, rebellion against the nobles in northern France formed around Raymond VI and his son Raymond VII. They recaptured much of their lost territory, and Simon de Montfort was killed during the siege of Toulouse. This left a power vacuum at the head of the Catholic forces in northern France. This mantle was taken up by King Louis VIII.

Louis was able to restore northern French control over the south, and by 1226, he had successfully prevented Raymond’s dream for an independent Toulouse. In 1229, Raymond VII was finally brought to the table and accepted a peace treaty in which he forfeited all of his ancestral lands to the monarchy upon his death. The French crown may have been late to the crusade but gained significantly by the time it ended.

Religious Civil War

The Albigensian Crusade had dramatically reduced the power and wealth of the nobility of southern France. It had also reshaped the royal political map of France.

The Cathars, ultimately, were not wiped out, going underground or leaving France, and their churches continued in the region on a much-reduced scale. To combat this continuing heresy, the Catholic Church set up an Inquisition, hoping to convert through argument rather than violence. It was a slower approach but much more successful, and the Cathars had effectively disappeared by the 15th century.

For all of its violence and destruction, the Albigensian Crusade had failed in its stated aim to remove heresy from Southern France. However, it did provide a solid framework of new secular lords willing to work with the church against heretics. It also established a successful and efficient Inquisition system.

Additionally, due to the violence and cost of the crusade, there was little desire to join the subsequent crusades launched by the Church. It increased the power of the French monarchy but perhaps made the Papacy more dependent on it.

Many destructive and evil acts were performed in the name of Holy War. But with this crusade, against neighbors and countrymen, for the first time we see the greed and violence underneath the religious smokescreen. With this crusade, the stage is set for the horrors still to come, in God’s name.

Top Image: The French nobility, hidden in a cloak of piety, massacred the Albigensians. Source: Serhiibobyk / Adobe Stock.

By Kurt Readman