This is the story of one of the most audacious projects ever undertaken in the Cold War. The rival superpowers of the US and the USSR faced off against each other by land, air and sea.

In such a conflict knowledge was the ultimate weapon. Knowledge of the enemy’s plans, knowledge of their capabilities and their weapons, would grant an advantage. Espionage was a key component in warfare, but rarely was either side offered the chance to spy on the enemy as great as was presented to the United States in 1968.

Six years in the making and still to this day officially classed as a failure, Project Azorian was nothing short of breathtaking in its ambition. The CIA, the United States Central Intelligence Agency, set their sights on nothing less than recovering an entire Soviet submarine from the sea, intact.

Such a vessel would be a treasure trove of intelligence information. Neither side ever conceived of a realistic possibility where the enemy would have access to one of their submarines, and the value of being able to tear apart one of these vessels to discover its secrets was immense.

But stealing an $800 million submarine with its payload of nuclear ballistic missiles in plain sight was no small feat. The CIA needed a cover story, and a front man to distract the attention of the world while they retrieved the submarine. They needed a man who had ambition, wealth, and expertise in engineering, wrapped up in an eccentric public personality.

They needed Howard Hughes.

A Missing Submarine

The precipitating point for this grand plan was March 1968. The Soviet ballistic missile submarine K-129 had departed on her third patrol in the Pacific Ocean. The submarine carried three R21 “Serb” nuclear missiles, which could be launched while submerged and which had a range of up to 1,600 nautical miles (2,950 km).

Sometime in the first days of March, something happened on the submarine. Her captain stopped the regular reports to Soviet submarine command, and by the third week of March she was officially declared missing.

Given the length of time since K-129 had last reported in, and the vastness of the Pacific, the Soviets did not know where the submarine was. The post-Cuban Missile Crisis era, where both Soviet and American submarines were silently patrolling the seas with nuclear weapons on high alert, showed how ready both the countries were for any sort of potential war.

Some reports suggested that the sinking of K-129 could be due to some form of mechanical error within the missile engine ignition section. But the Soviets, at that time, suspected the possibility of foul play by the Americans.

The Soviet search was comprehensive, but ultimately fruitless. After two months spent searching for K-129 by the USSR, they abandoned the effort, writing off the boat and her crew as lost. Wherever K-129 was and whatever happened to her would have to remain unexplained.

However, the US had sophisticated listening systems in the Pacific and their analysis of the acoustic data found an anomaly. They had picked up the sound of an implosion on 8 March 1968, and they knew exactly where the explosion had occurred. Unlike the Soviets, they knew where K-129 was.

Project Azorian

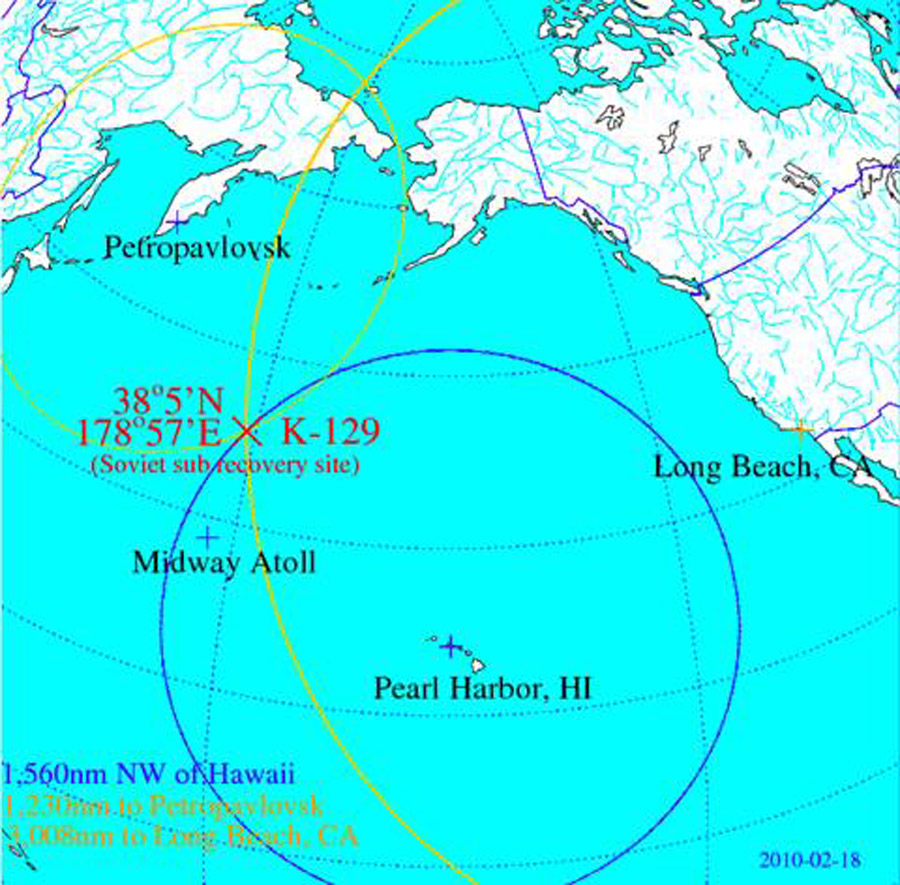

K-129 had gone down around 1,500 miles (2,400 km) northwest of the island of Hawaii. The sea bed was at a depth of 16,500 feet (5,000 m), and no country had ever succeeded in recovering such a heavy and big object from such deep waters.

The submarine was undoubtedly about to offer a plethora of information about the Soviet warheads and weapon systems. The value of K-129 was too great to ignore.

And so the CIA got to work, gaming out a scenario in which such an immense undertaking could be successfully carried out. Several ideas were suggested, such as inflating gas balloons under the hull of the vessel to push the submarine up to the surface.

But in the end, they decided upon an idea similar to that of a classic arcade game: the use of a gigantic claw. With the huge claw, the Americans planned upon grasping and pulling the K-129 submarine into the belly of a huge, custom-built ship.

The plan was assessed as having only a 10% success rate. But the real danger lay in the Soviets finding out about the plan. The US authorities were concerned about the potential reaction the Soviets might have if they discovered Project Azorian, and how destabilizing it might be to the fragile peace between the superpowers.

The Cover Story

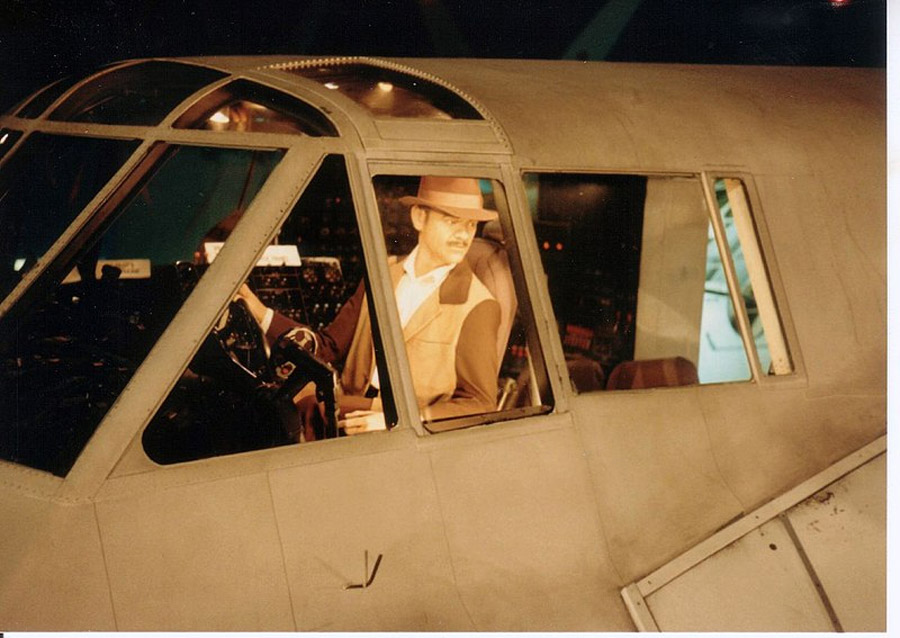

In order to ensure their true plans remained secret, the CIA decided to construct a cover story with the assistance of Howard Hughes. Hughes was an eccentric billionaire and aviator, known for immense construction projects such as the Spruce Goose, the largest wooden plane ever built.

The story put forward was that Howard Hughes was constructing a 618-foot (188 m) long ship, called the Hughes Glomar Explorer. The ship was advertised as a research vessel for deep-sea mining, retrieving manganese nodules from the seabed. For this it was outfitted with a massive moon pool (an opening into the sea at the bottom of the hull of the ship) and a massive claw.

The project was complex and years in the making, but in 1972, the champagne christening celebration was done, and a press excitedly covered the launch of the new ship. The Los Angeles Times described the ship as “shrouded in secrecy” and there was much speculation as to her capabilities.

The news piece also stated that “The Newsmen were not allowed to witness the launch and other details of this ship. The destination and mission of this ship are not yet released.” But this is where the presence of Hughes was beneficial: a famous recluse, the newspapers chalked much of the mystery up to his eccentricities.

The Recovery

By June 1974 all sea tests were done, the claw was installed, and the fully outfitted Glomar Explorer headed to the resting point of K-129. Soviet ships were closely monitoring the vessel and her activates, and it is now known that the USSR had been tipped off about the true nature of the project. Luckily for the CIA, the Soviets had dismissed the story as wildly implausible.

Salvage operations took several weeks of slow progress, and apparently were successful in retrieving part of the submarine from the ocean depths. However, the CIA have maintained that the crucial area of the submarine containing the missiles was lost when one of the claw arms broke during retrieval, sinking back to the sea bed beyond their reach.

Of course, part of any good intelligence agency is the spreading of misinformation, and the CIA would likely never confess to recovering the missiles in any event. Persistent rumors since the project state that the submarine was recovered intact and gave up its secrets, offering the US a significant edge in the cold war.

There is also the unanswered question of what happened on K-129. Some believe that her location was not where the CIA declared, but that instead she was preparing a covert attack on US facilities on Hawaii with her nuclear missiles, when something happened aboard and she sank.

Do the CIA know more than us about the outcome of this project and the events on K-129? Almost certainly. Are they likely to release this information any time soon? That seems as unlikely as Project Azorian itself.

Top Image: The Glomar Explorer. Source: U.S Government / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri