The great tales of ancient Greece are some of the finest and most enduring ever told. The imagery of great warriors clashing and fighting to the death in epics such as the Iliad have resonated down the millennia, and much energy has been expended in finding the true world behind these myths.

Royal tombs have been unearthed at ancient Mycenae, and Troy was excavated, and partially destroyed in the process, in western Turkey. But what of the fighters, what of these larger-than-life central figures who power the narrative and fascinate the author. Did they really exist as well?

It seems they did.

Tomb of the Great Warrior

The Griffin Warrior Tomb is a Bronze Age shaft tomb near Pylos, Greece, that dates from circa 1450 BC. A study team led by husband-and-wife archaeologists Jack L. Davis and Sharon Stocker, supported by the University of Cincinnati, uncovered the grave only recently.

From May to October 2015, the tomb site was explored. The study team discovered a complete adult male skeleton and almost 1,500 artifacts, including weapons, gems, armor, and silver and gold artifacts, during the initial six-month excavation.

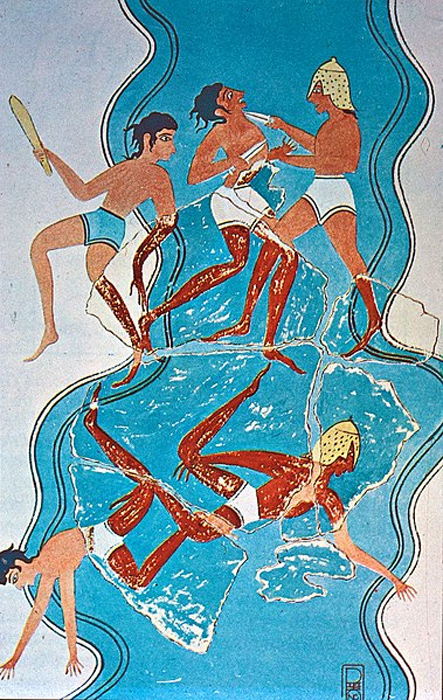

Since 2015, the site has given up approximately 3,500 artifacts in total, including what is known as the Pylos Combat Agate, a stunningly beautiful Minoan sealstone depicting warriors fighting. A further four signet gold rings were also uncovered with detailed depictions from Minoan mythology.

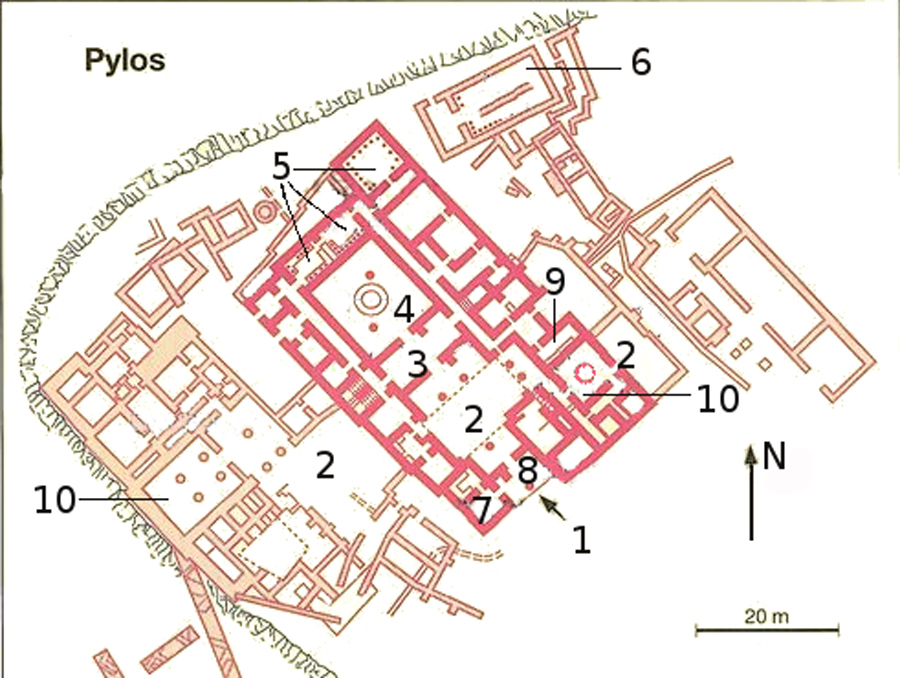

The tomb was unearthed in an olive grove near the ancient Palace of Nestor in Pylos, in southwest Greece. Nestor is a peripheral figure in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and his Bronze Age palace is one of the few locations in those epic tales which has been pinpointed with any confidence.

Davis and Stocker, the excavation leaders, only found the tomb by chance, having initially intended to dig downhill from the Palace. They were unable to obtain a permit for their intended site due and were instead permitted to excavate in a neighboring olive grove. Here they literally struck gold.

The Palace of Nestor

The so-called Palace of Nestor, near Pylos, is the most entirely preserved of all Bronze Age palaces on the Greek mainland. In 1939, archaeologist Carl Blegen, a professor of classical archaeology at the University of Cincinnati, undertook an excavation to find the palace of the legendary ruler, with the help of Greek archaeologist Konstantinos Kourouniotis.

Blegen chose Epano Englianos, a hilltop site in Messenia in the far southwest of Greece, as a suitable location for the ancient ruins. The excavation discovered the ruins of several structures, tombs, and the first traces of the ancient Greek writing known as Linear B.

The site, even if not the Palace of Nestor, was still a large and very important Greek city built around a richly decorated central complex. Here were traders and merchants, priests and rulers of a large population. And here, too, were warriors.

Who was the Griffin Warrior?

The Griffin Warrior Tomb is one of the most intriguing archaeological discoveries since it appears to connect the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations. The tomb shares features of both civilizations and offers an insight into the link between the Mycenaeans on the Greek mainland, and the mysterious Minoans of Crete.

The grave itself dates from the Mycenaean Civilization, which lasted from 1750 BC to 1050 BC. However, several of the artifacts discovered appear to be from the much older Minoan Civilization, which lasted from 3500 BC to 1100 BC. The Mycenaeans had reached most of the eastern Mediterranean, including ancient Egypt, the city-states of the Near East (today’s Turkey), and the Mediterranean islands, according to archaeological evidence.

The strongest link revealed, however, is with the Minoan Civilization on the Greek island of Crete. Named in modernity after the mythological King Minos, the islanders’ civilization differed greatly from that of mainland Greece, and little is known of this civilization.

The dig began near three stones that looked to form a corner of a structure. After initial excavations a shaft measuring two meters by one meter (6 by 3 feet) was unearthed. A stone-lined compartment contained a wooden coffin inside the shaft.

Inside the chamber and on top of the coffin, the tomb was littered with offerings such as jewelry, seal stones, carved ivories, combs, gold and silver goblets. Bronze weapons were also found in the tomb: this could only be the resting place of a great warrior.

- The Secret Gods of the Greek Pantheon: Who Were the Cabeiri?

- Where is the Tomb of Alexander the Great?

A gold box-weave chain with sacral ivy, a meter-long sword with a gold-coated hilt, a gold-hilted dagger, and various gold and silver cups were among the relics. Carnelian, amethyst, amber, and gold beads, four gold rings, and a plethora of miniature carved seals were also found, depicting fighting, goddesses, reeds, altars, lions, and men leaping over bulls, a Minoan tradition.

A bronze mirror with an ivory handle, thin bands of bronze from the warrior’s armor, boar tusks, possibly from the warrior’s helmet, and other items include an ivory plaque depicting a griffon in a rocky landscape, a bronze mirror with an ivory handle, thin bands of bronze from the warrior’s armor, were also found. This man had been buried with the finest armor and weaponry available.

Could He Be A Figure From Legend?

Could the man buried in this tomb be someone we have already heard of, perhaps a figure from the Iliad? The skeleton’s analysis revealed that the man was in his 30s, stood roughly 5 feet tall, and had long hair, implying that he was a wealthy, important member of society.

He was clearly both rich and powerful, dying in his prime and buried with artifacts created with a level of artistry and precision not known until much later. The Combat Agate in particular continues t fascinate, with the human figures depicted with a level of detail and musculature not seen until the classical period of Greek art, some 1,000 years later.

Sadly, there is nothing in the tomb to conclusively link the warrior to a known figure from myth. While there are several candidates, nothing can be proven with certainty and it can only, at this point, be said that here lies a great warrior.

Davis and others argue that the burial offers a more important lesson, given the rise of nationalism and xenophobia in areas of Europe and the United States. Greek culture has not been genetically transferred from generation to generation since the dawn of time, Davis asserts.

Mycenaeans, he claims, almost from the first were accretive in their growth, absorbing surrounding traditions and incorporating them into the whole of what it meant to be “Mycenaean”. With its untouched treasures and intact skeleton, the Pylos grave provides a practically unprecedented insight into this period. And what it exposes is challenging the most basic notions about the origins of Western civilization.

Top Image: What can the Griffin Warrior tell us about the ancient Mycenaeans and Minoans? Source: Breakermaximus / Adobe Stock.