During Josef Stalin’s time as the leader of the Soviet Union, from 1928 -1953, there were many “internal exiles”. These exiles created camps known as forced settlements across Siberia. People would be deported to uninhabited land in Siberia based on their social class, nationality, and sometimes to clear up some space in prisons and gulags.

These forced settlements sounded better than gulag labor camps; people could live with families once deported and move about the settlement more freely than in a gulag. However, the people deported were seen as second-class citizens and were barred from working in certain professions.

They were not permitted to return to where they were from or attend any of the prestigious universities in Russia. The environments these forced settlements were established in were brutal, and the conditions of the Siberian taiga made survival difficult.

One of these forced settlements was established on a deserted island in northwestern Siberia and collapsed into chaos shortly after the settlers were dropped off. More than just the freezing temperatures, the lack of preparation and extremely isolation doomed the deportees almost as soon as they were dropped off on Nazino Island.

A lack of resources resulted in the formation of violent gangs, murders, widespread illness, deaths, and, in the desperation of the men and women trapped there, cannibalism. How did it come to pass that in only 13 weeks, Nazino Island became known as Death Island or Cannibal Island and saw the deaths of thousands of people?

The Plan

In February 1933, the head of the Soviet secret police, Genrikh Yagoda, and the head of the GULAG system, Matvei Berman, approached Josef Stalin with a proposal for a new labor camp. The proposal was for two million people to be deported to Siberia to form “special settlements”.

These settlements were created to bring more than one million hectares (2,500,000 acres) of unsettled “virgin land” into self-sufficient, productive towns that could contribute to the Soviet Union. This two-year predicted timeline for self-sufficiency came from results from the dekulakization effort three years earlier.

A kulak was a peasant who was wealthy enough to own farmland and hire workers, but the Soviet Union chose to collectivize the kulak’s farms and deport them to remote areas of Siberia. After two years, the deportees had become self-sufficient, which was a surprising success, and Yagoda and Berman expected the same to occur in their plan.

This wasn’t surprising if we consider the kulaks and their employees operated farms and knew how to cultivate the land and build shelters. The Soviet authorities thought the kulaks were too stupid to be able to survive in the middle of Siberia.

- Was There Cannibalism in the Donner Party?

- Cold Hearted: Why Did Empress Anna Ivanovna Build An Ice Palace?

Stalin approved the plan even though a famine in the Russian countryside limited supplies for this new settlement. Stalin also decreased the number of deportees from two million to one million, but he still sent a lot of people into the frozen north to die.

Nazino Island

After passing through and dropping off a large number of deportees in transit camps along the way, many deportees from urban areas like Moscow and Leningrad (present-day St. Petersburg) were sent to Nazino Island (остров Назино). Nazino Island is a river island on the Ob River 500 miles (800km) to the north of the city of Tomsk.

The island itself is a 1.9 mile (3km) long and only 660 yards (600m) wide, a swampy and desolate piece of land. This area of Western Siberia was sparsely populated, and only a few groups of indigenous Ostyak peoples lived in the area.

The people sent to Nazino were prisoners, criminals, city residents, and what were called lumpenproletariat (people of such a low social class that they lacked class consciousness). They were sent there to be as far away as possible: in effect, they were sent there to die.

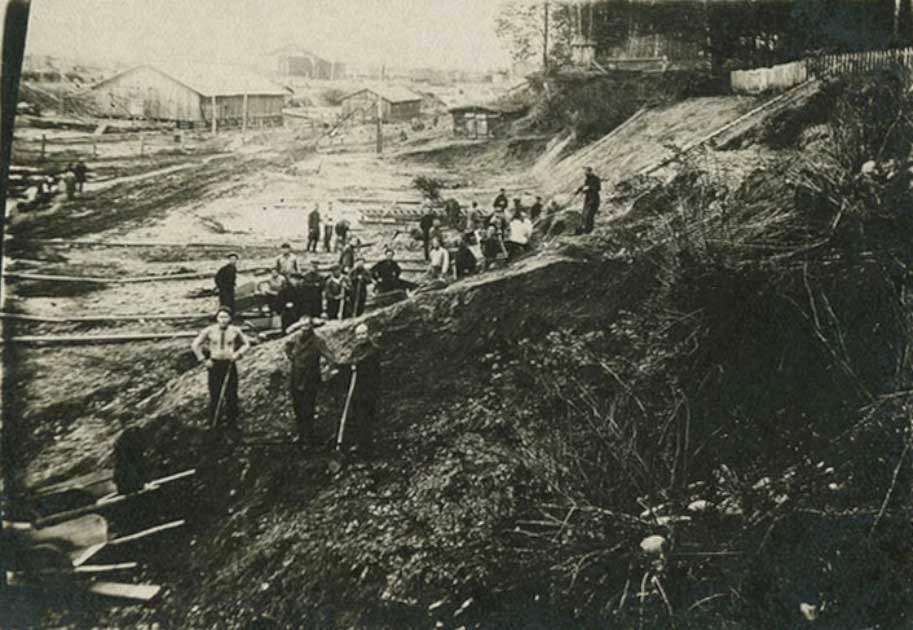

On May 18, 1933, the first group of deportees (around 322 women and 4,556 men) arrived on the island. By the time the barges arrived at the island, 27 people had already died in transit and over a third of the deportees were unable to stand due to weakness.

On May 27, 1,200 more deportees arrived along with 20 tons of flour at Nazino Island. Immediately a fight broke out when the flour was dropped off, resulting in guards firing at the starving deportees and relocating the flour to the other side of the island, but all the same the fight continued.

To prevent riots over food, people were chosen to deliver the flour rations to groups of 150 people. That sounds good, but most of these people were criminals who would eat or hoard the flour for themselves.

And it wasn’t just food that was the issue on Nazino, the 6,000 deportees were dropped off with what they were wearing when arrested, and no tools or building materials were given to the new inhabitants of the island. The lack of materials meant no shelter, scant food, and the guards across the river with guns would shoot anyone who tried to swim across the freezing cold Ob River to escape.

All Hell Breaks Loose

Unlike the kulaks from the first deportation experiment years earlier, the deportees on Nazino Island did not know about basic farming, how to clear the land, and how to cultivate the island to make it hospitable. Instead, not long after people arrived on Nazino Island, criminals formed gangs that terrorized other settlers.

The small amounts of flour each person received (four days after arriving on the island) couldn’t be baked because there were no ovens. Instead, people mixed water from the river with flour to make a paste-like “meal.” Unable to boil water to decontaminate it, many people on Nazino Island developed dysentery.

If the people on the island didn’t die from dysentery, they began to die from the spread of typhus or other diseases, or authorities hunting the starving deportees. Murder was rampant and occurred during fights about food, money, and dead bodies with gold fillings and crowns that could be looted.

- Rescuing the Dead: The Frozen Coffins of Svalbard

- Siberian Mystery Ruin: What Was Por-Bazhyn and Why Was it Built?

The people on Nazino Island died in other terrible ways, like starvation, hypothermia/exposure, exhaustion, and some people who had built a fire and fell asleep in front of it would be burnt to death. Not long after the deportees were abandoned on Nazino Island, Stalin rejected the plan, but it took a month to travel to the island to evacuate the deportees. In that month, the conditions on Nazino Island only got worse.

Cannibal Island

The first incident of cannibalism occurred only ten days after the second group of deportees arrived on the island. People were so hungry that they accepted the taboo of eating other humans.

A harrowing account survives from a 13-year-old girl about cannibalism on the island, particularly one incident involving a guard’s girlfriend. The girl said, “When he left, people grabbed the girl, tied her to a tree, and stabbed her to death, eating everything they could. They were hungry and wanted to eat. All over the island, one could see human flesh being ripped, cut, and hung on trees. The clearings were littered with corpses.”

Due to the horrors of murders and cannibalism, the island became known as Cannibal Island or Death Island. A woman in the village of Nazino shared a story about one of the survivors. According to her, “Once, an old woman came from the Death Island… I saw that the old woman’s calves had been chopped off. When I asked her, she said: ‘They were cut off on Death Island and grilled.’ All the flesh on her calves had been cut off.”

Some people on Nazino Island would only eat a person on the brink of death and saw their depravity as a gift to the dying person. They would die then and would not have to suffer for a few more days before succumbing to death.

Others began killing people to eat them regardless of age, gender, or health status. Even after the survivors of Nazino Island were evacuated, they were sent to other Siberian camps and gulags, where they continued to starve to death and die of exposure in cold barracks. The world would have never learned about the tragedy on Nazino Island if it wasn’t for one man, Vasily Velichko.

The Report

Velichko was a member of the Narym district committee of the Communist Party, and he was sent to a labor settlement in July of 1933 to report on “how successful and productive the camp was”. Once Velichko began hearing horror stories about Nazino Island from survivors, he switched from writing a report full of Soviet propaganda and instead started investigating what happened on Nazino Island.

Velichko’s report was based on the testimonies of around a dozen Nazino Island survivors. Once it reached the Kremlin, a special commission was created to investigate what happened more intensively. The special commission found 31 mass graves with 50-70 bodies in each one. The commission also found that out of the estimated 6,000 deportees who arrived at Nazino Island, 4,000 had died or were missing.

As a result of both Velichko’s report and the special commission’s investigation, over 80 deportees and guards were prosecuted by the Kremlin. Twenty-three people received sentences of capital punishment for what was listed as “looting and assault,” and eleven people were charged with cannibalism.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s, just before the collapse of the Soviet Union, that people learned about Nazino Island. Due to Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost policy which pushed for more “openness” and transparency from the government, the Velichko report was able to be read by non-government officials.

Every year (unless deterred by flooding of the Ob River), Tomsk and Nazino village locals will place a wreath on a cross on the island in memory of those who perished on Nazino Island in 1933.

Top Image: The Nazino tragedy led to the location becoming known as Cannibal Island. Source: Nito / Adobe Stock.

By Lauren Dillon