By far our greatest resource for understanding our past is what has been written about it. Information from archaeology, while a vital facet of piecing together human history, gives us only dead places and dead people, and records, documents and language are needed to breathe life into it.

In this we are lucky. The two great languages of history in the western world, Latin and Greek, have been preserved through near constant (if increasingly archaic) usage, and we can trace a near unbroken line from the use of these languages today through those who spoke them for the first time.

Other great languages enjoy a similar link, such as the dialects of China, India, or Arabic. But not all empires survived, and not all texts from history can be read today. What secrets could these mysterious artifacts contain, awaiting only a moment of academic brilliance or their Rosetta Stone to unlock them?

Here are ten examples from history of texts we cannot decipher.

1. Ancient Minoan

The island of Crete is the largest of the Greek islands and in antiquity was home to the Minoans, possibly the only true thalassocracy (a civilization led by seafarers) in history. Magnificent ruins dot the island, not least the great palace at Knossos, likely the original for the Greek myth of the Minotaur.

Happily, the Minoans left examples of their early language, most famously in the form of the Phaistos Disc, a pottery circle with a spiral of the pictographic script. Other less decorative examples of the Minoan script, known as Linear A, also survive. This language, despite all the examples which we have and despite occasional claims of a solution, has never been deciphered.

We know the Minoans moved to using Linear B around 1,500 BC, a proto-Greek language that is trivial to understand by comparison. But, without this first and entirely mysterious script being translated, almost everything about this great and strange civilization remains entirely unknown.

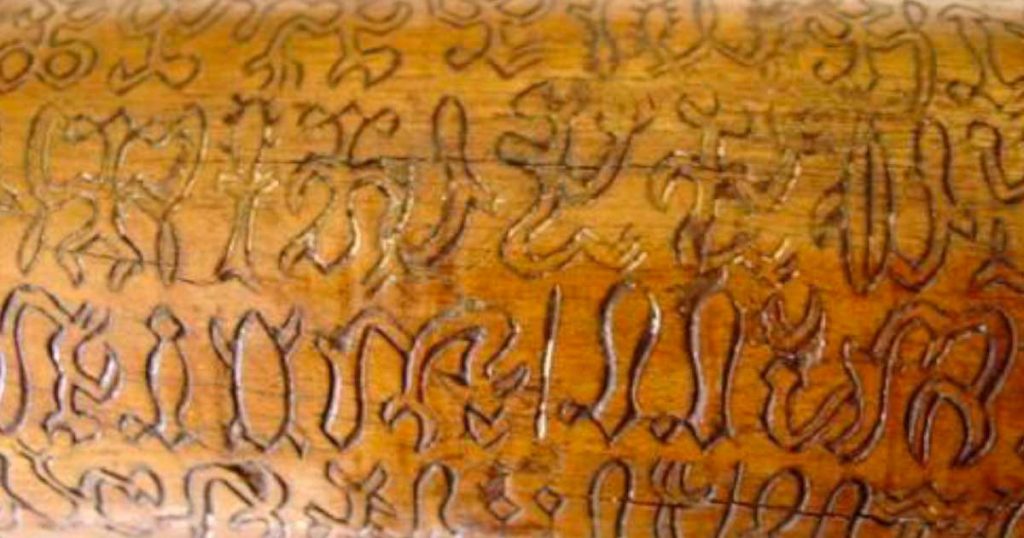

2. The Rongo Rongo script

In 1864, a Spaniard named Eugène Eyraud reported the existence of a strange pictographic script on Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island. The script, written on pieces of wood, was called “Rongo Rongo” which in the native language means “to chant”.

By this point, Rapa Nui was a shell of its former self, colonized by the Spanish in 1770 and devastated by European diseases. By the 1860s only about 3,000 people remained on the island, and fully half were then kidnapped by Peruvian slavers in 1862.

This dramatic loss of life meant that many things about the island were lost, not least its history. And with nobody alive who can remember how to read the ancient scripts, and too few examples surviving to attempt a reconstruction, it seems that the traditional history of Rapa Nui has been lost forever.

3. Sawgoek

Sawgoek literally translated to “root script” and it is well named, being referenced in the creation mythology of the Chinese Zhuang. The primeval creator god Baeu Ro gave the text, consisting of 4,000 symbols, to his people along with other useful gifts like fire. Sadly he did not provide instructions.

When the Zhuang people tried to use fire in their homes, they burned them down and lost the Sawgoek script as well. The story would seem to end there, a life lesson in adequate fireproofing and the need for backups, except that some examples of sawgoek appear to have survived.

This descendent language, properly called Sawveh, consists of some 140 known symbols dating back to the Neolithic. Some doubt whether these symbols together even constitute an entire language, but it is probable that we will never know.

4. Harappan

The Harrapans of the Indus Valley on the Pakistan/India border are probably the greatest ancient civilization you have never heard of. From 3,300 BC these builders, administrators and lovers of lapis lazuli built their sophisticated cities, mined in the mountains and traded what they found, and communicated with each other in a language which seemingly differs from every other.

Much of what survives of the Harappan language speaks to their practical nature. The pictographs are generally found on seals and were likely used to label goods or other items, and were therefore a solution to an existing problem rather than a creative medium.

This also makes deciphering the text very problematic, as almost all Harappan writing survives as very brief snatches of text, without context. However much progress has been made in attempting to understand Harappan text, and it is hoped that one day soon we may learn more about the culture of these ancient peoples.

5. The Text of the Rohonc Codex

The Rohonc Codex came to light in the city of Rohonc in Hungary in the 19th century, and immediately caused a storm. This small, leather bound book was crammed with strange diagrams and spidery notes, all in an entirely unknown language.

What can be pieced together about the text is fascinating. Depictions of Christians, Hindus, Muslims and pagans exist alongside each other, and the paper it was written on dates back to around the 16th century.

Some debate whether the text is even a script at all, citing the large number of symbols and lack of repetition, and some suspect that the Codex may be nothing more than an 18th century forgery. But what the Codex says and who was supposed to read it, are a complete mystery.

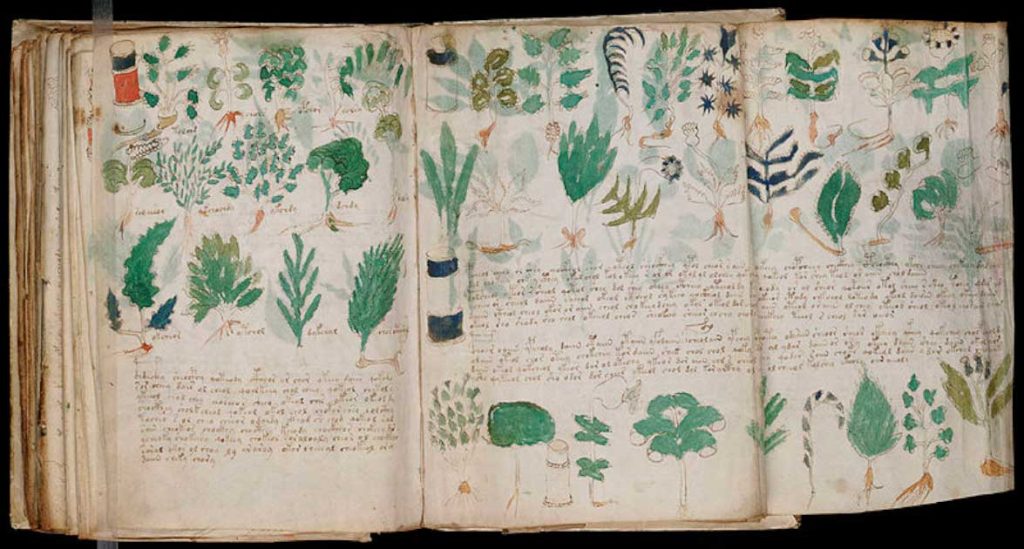

6. The Text of the Voynich Manuscript

Another crazy text, the Voynich Manuscript defies almost all rational explanation. Firmly dated to the early 15th century, this large codex written on vellum apparently comes from the early Italian Renaissance.

Its pages are covered in lines of a written text which defies all attempts at translation. Further, the diagrams which cover its pages are similarly confusing, depicting objects and scenes at once greatly detailed and utterly baffling. Groups of people dance naked with stars, or sit trapped in what appear to be fruit.

Frustratingly, modern language analysis of the script suggests that there may be a real language to decipher here, although as with the Rohonc Codex many doubt whether the Voynich Manuscript is a real text rather than a joke of some kind. But the best guess so far, that the text is some kind of guide to herbal medicine, is all we have.

7. The Starving of Saqqara

Ancient Egypt is very ancient indeed, and if you are looking at history from before the first Egyptian dynasty then you are truly looking at the dawn of civilization. Therefore when a statue of such as age covered in a script came to light in the early 20th century it caused a storm.

The Starving of Saqqara (a modern name referring to the necropolis at Memphis for unknown reasons) depicts two naked figures with strange proportions, facing each other with an odd script carved into their backs. If this predates the rise of dynastic Egypt, it is at least 5,000 years old.

In truth, we know more about what this script is not that what it is. The text has been analyzed against known ancient languages, and it bears no relation to ancient Aramaic, Demotic, Hebrew, Syriac or any later Egyptian text. Whoever created this statue, they were using a sxcript completely unknown to us.

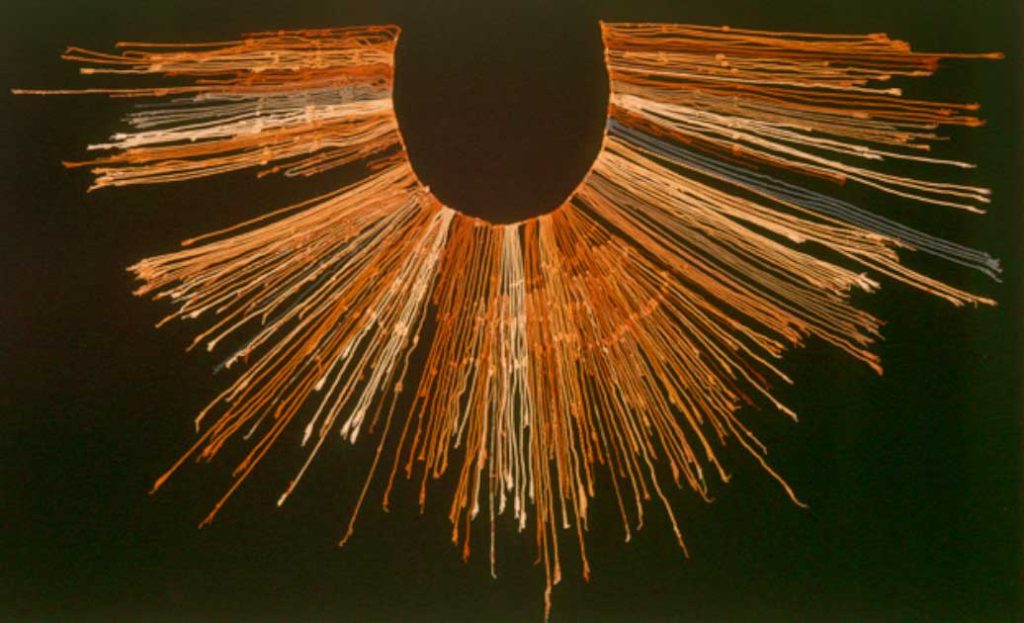

8. Quipu

The Inca, the last great pre-Columbian civilization of the Andes, had a recorded language based on knots and string. Different colors and lengths of string would combine with different patterns of knots, primarily to keep records of business transactions of store levels at the omnipresent storehouses that knit the empire together.

Pizarro and the Spanish conquistadors, untrusting of a communication system they could not read and fearful that the native population might use it to plot against them, had huge numbers of Quipa records destroyed and suppressed its use as a writing system. The intricate knotwork fell into disuse and was eventually forgotten.

Nowadays we can say the Inca counted in base ten, like we do, but very little else besides. A project is actively underway to understand and decode Quipu, and to find out as some hope whether there is a hidden Inca mythology somewhere in the knots and strigs that remain.

9. The language of the Ikom Monoliths

In Cross River State in southern Nigeria, around 300 stone monoliths can be found arranged in circles across the landscape. Made from volcanic stone, and carved between the 16th and early 20th centuries they stand between one and six feet high (0.3 to 1.8 m).

What makes these stones unique are the carvings found across them. These carvings, consisting of repeating patterns, stylized faces and inscriptions have fascinated archaeologists almost as much as they have baffled them.

But time may be running out to unlock the secret of the stones. The Alok Ikom monoliths are threatened by exposure to heavy rainfall, which erodes the patterns carved on them.

In addition, the high humidity and extreme heat in Cross River State damaged the delicate outer surface of the stones, and falling trees have led to further damage. Vandalism and theft of the valuable stones also threatens them

10. Olmec

The Olmec Civilization is one of the least understood and most mysterious in the ancient world. Known for their colossal stone head sculptures, they first emerged in the Gulf of Mexico near present-day Tabasco and Veracruz in 1600 BC. They subsequently became a dominant agricultural and trading power.

In the early 1990s, construction workers building a road in Veracruz discovered an ancient serpentinite tablet called the Cascajal Block. It contains the earliest known example of Olmec writing. Carved around 900 BCE, the Cascajal Block contains 62 glyphs in 28 different patterns. Although researchers believe the block follows grammar and syntax rules, they cannot yet decipher these glyphs. However, they theorize that the tablet could have had legal, commercial, or religious use.

Barring any breakthrough discoveries, this ancient Mesoamerican culture will remain a tantalizing mystery.

Top Image: Detail from the Phaistos Disc: the Minoan language of Linear A remains undeciphered, and are apparently related to the pictographs on the disc. Source: User Asb / CC BY-SA 3.0.

By Joseph Green