Whether or not you believe in luck, it is true that some people seem always able to beat the odds. Take for example Violet Jessop, an Argentine woman of Irish heritage who had the useful habit of surviving deadly shipwrecks.

Fondly referred to as the “Queen of Sinking Ships” and “Miss Unsinkable”, Violet not only survived one sinking ship but three. As it turns out, however, her death-defying luck started well before she ever stepped foot on a ship.

Early Life of Violet Jessop

Violet Jessop was born on 2nd October 1887 near Bahia Blanca in Argentina. She was the oldest of William and Katherine Jessop’s nine children. It could be said her luck started early in life as only six of the Jessop’s nine children survived and made it out of childhood.

Violet had an early brush with death as a child when she contracted tuberculosis. Her doctors predicted that her tuberculosis would be fatal, but as would prove to be a habit, Violet survived her first dance with death.

When Violet was sixteen she lost her father due to complications from surgery and what remained of her family decided to move to England. Violet spent her first years in England attending a covenant school and caring for her siblings while her mother went to work at sea as a stewardess.

Eventually, Violet’s mother became ill, forcing Violet to leave school and follow in her mother’s footsteps by applying to be a stewardess. Supposedly, the strikingly attractive Violet had to dress down to get her first job and at age 21 she was hired on as a stewardess with the Royal Mail Line. Her first ship was the Orinoco, which she joined in 1908.

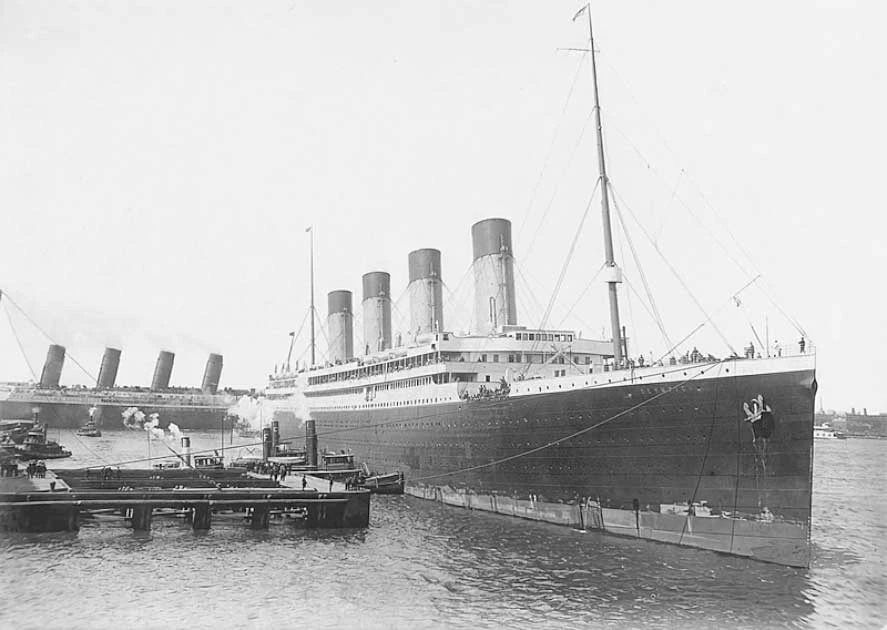

Violet Jessop was good at her job and by 1911 she had signed on with the prestigious White Star Line. Her first ship with them was the RMS Olympic, which at the time was the largest civilian liner in the world.

On the 20th of September 1911, the Olympic collided with the HMS Hawke, a British warship, shortly after leaving Southampton. The collision wasn’t too bad, there were no fatalities and despite fairly severe damage, both ships managed to make it back to port without sinking.

While surely a frightening experience it wasn’t enough to dissuade VIolet from life at sea. She continued working on the Olympic until April 1912. April had proven herself an adept stewardess and as such, she was transferred to the Olympic’s sister ship and the White Star Line’s crown jewel, the Titanic.

Only the Start

It should come as no surprise that Violet’s time on the Titanic was short-lived and didn’t go without incident. She boarded the RMS Titanic on the 10th of April 1912 at the age of 24. Four days later it sank.

On the 14th of April, the ship struck an iceberg as it sailed through the North Atlantic. It sank around two hours and forty minutes later. The story of how it was believed the ship was unsinkable is infamous.

In her memoirs, Violet recalled how after the initial collision she was ordered to go on deck and act as an example of how to behave for the ship’s non-English speaking guests. She was on deck as the crew loaded and lowered the lifeboats (of which there were far too few).

Violet was one of the lucky few who was given a place on a lifeboat. She was ordered into lifeboat 16 and just as it was being lowered one of the ship’s officers handed her a baby to protect.

Violet’s luck held out and the next morning the occupants of her lifeboat were rescued by the RMS Carpathia. They were taken to New York on April 18th. Her time on the Titanic actually has a happy ending. In her memoirs Violet recalls how during her time on the Carpathia she was approached by a woman (hopefully the baby’s mother) who scooped the baby out of Violet’s arms and ran off crying, never uttering a word.

After a brief time in New York Violet was shipped back to Southampton, ready for her next misadventure.

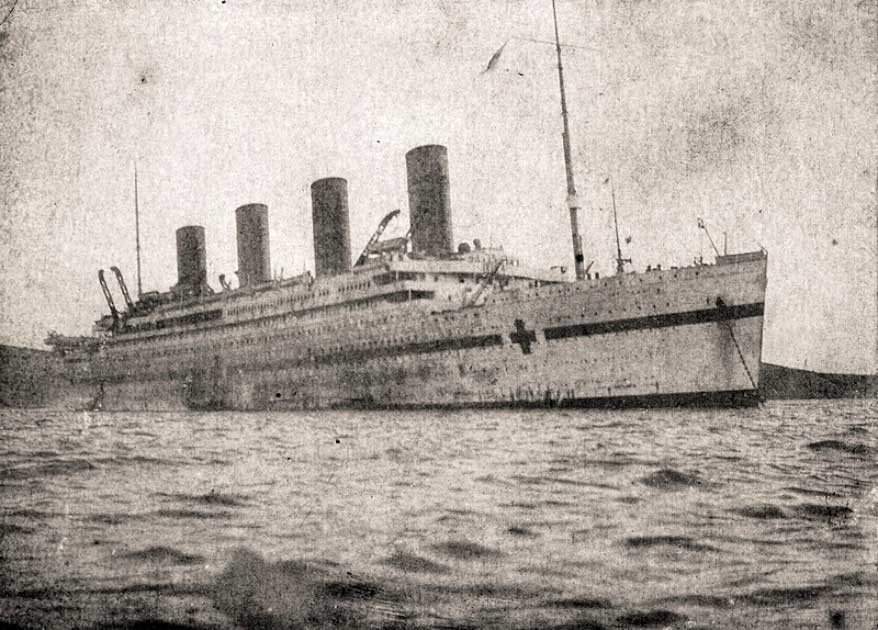

When World War One broke out Violet chose to join the war effort and joined the British Red Cross as a stewardess. This would lead to her third nautical brush with death.

By the 21st of November 1916, she was serving on the HMHS Britannic, the younger sister ship of both the Titanic and Olympic. Like many luxury ships, it had been converted into a hospital ship.

- MV Joyita: The Ghost Ship that Couldn’t Sink

- The Other Titanic? SS Waratah, the Lost Ship Of South Africa

On the morning of the 21st of November, the ship was hit by an unexplained explosion as it sailed through the Aegean Sea. Within 55 minutes it had sunk beneath the waves, killing 32 of the 1066 people onboard at the time.

At the time it was believed the ship was either hit by a German torpedo or a mine. In 2016 a diving expedition showed the latter to be true, the ship had hit a deep sea mine left by the Germans.

The Britannic was perhaps Violet’s most dramatic brush with death. As the ship was sinking Violet and the other survivors were nearly turned into minced meat by the ship’s propellers. She was forced to jump out of her lifeboat as it threatened to be swallowed by the deadly blades, resulting in a traumatic head injury.

Later Life

Happily, Violets survived her head injury and carried on life at sea. In 1920 she went back to work for White Star Line before moving over to Red Star Line and finally the Royal Mail Line. Her good luck held out and she wasn’t involved in any more accidents at sea.

At the age of 36, she married John James Lewis but they divorced a year later. In 1950 she retired and moved to Great Ashfield in Suffolk, England. She ended up living a long life and died in 1971 at the grand age of 83.

Whether it’s lucky to survive three disasters at sea or unlucky to be caught up in three probably depends on whether one is a glass-half-full or glass-half-empty kind of person. Perhaps the greatest miracle here is that Violet chose to work with White Star Line for so long after being on three of their ships when they sank.

But perhaps Violet’s legacy shouldn’t be as the woman who survived three shipwrecks. One stormy night, many years after she had retired Violet received a phone call. The woman on the line asked if Violet had saved a baby the night the Titanic sank.

When Violet said she had the other woman said “I was that baby”, laughed, and hung up. Violet’s friend and biographer, John Maxtone-Graham, told her it was probably a prank. It couldn’t be she said, besides him, she had never told anyone.

The only baby recorded as being on Lifeboat 16 was a baby boy, Assad Thomas who was handed to Edwina Trout. The identity of the baby Violet saved remains a mystery.

Top Image: Violet Jessop is her Voluntary Aid detachment Uniform. Source: Unknown Author / Public Domain.