On 2 May 1982 the British naval submarine the Conqueror, fired upon and sank the Argentine light cruiser, the ARA General Belgrano. It is the only time in history that a submerged submarine has sunk an enemy surface vessel in combat, and of all the controversies surrounding the Falklands war, this would turn out to be the biggest.

In the decades since there has been much international debate on whether the UK had committed a war crime in their attack, or whether they were justified since technically the Argentines had started the war. As is so often true the answer isn’t clear cut and blame can be attributed to both sides. So what is the truth of the sinking of the Belgrano?

What was the Belgrano?

The ARA General Belgrano was an Argentine Navy Light Cruiser. She was an older ship that had been built by the New York Shipbuilding Corporation in Camden New Jersey in 1935. She first served in the US Navy as the USS Phoenix during WW2 before being sold to Argentina in 1951.

Before being sunk by the British during the Falkland war the ship had already survived several brushes with death. She was one of the few lucky American ships to have survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. She fought in the Pacific theater, earning nine battle stars for her service during the war.

After the war ended there was little use for her. The USS Phoenix was put into reserve and eventually decommissioned on 3 July 1946. She sat in Philadelphia for 5 years.

In October 1951 the USS Phoenix was sold to Argentina along with the USS Boise. The USS Phoenix was initially renamed 17 de Octubre, after “People’s Loyalty Day”, an important political symbol for the then-ruling party and its president Juan Peron.

Peron probably regretted the purchase. During the 1955 coup that saw him overthrown the 17 de Octubre was one of the main naval units that fought against him. After the coup, the ship was once again renamed, this time she was called the General Belgrano.

Manuel Belgrano was a lawyer who had founded the Argentine school of navigation, the Escuela de Nautica, in 1799. A national hero, he had also fought for Argentine independence during the war of 1811 to 1819.

Up until her sinking the Belgrano didn’t see much action. She accidentally rammed another Argentine ship, the Nueve de Julia during exercises in 1956, Both ships being only lightly damaged. The aging ship also received a retrofit between 1967 and 1968 during which she was rather ironically outfitted with a British-made missile system.

The Sinking

On 2 April 1982, Argentine forces carried out Operation Rosario, an attempt to invade and seize the Falklands Islands which were held by the British. The operation was the spark that ignited the Falklands war.

Argentina believed the Falklands to be part of their territory historically while the British felt they had ownership since they had held a colony there since 1841. As with so many historical territory disputes each side’s argument has some merit and the issue is still a bone of contention between the two nations 40 years later.

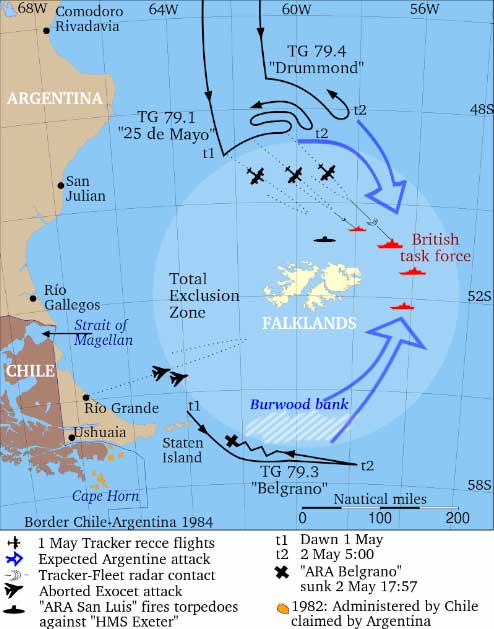

Whether Argentina was justified or not in their invasion is a topic for another piece, however. The important thing today is that Operation Rosario led directly to the sinking of the Belgrano. 10 days after the invasion Britain declared a 200-nautical-mile (370 km) maritime exclusion zone (MEZ) around the Falkland Islands.

The MEZ meant that any Argentinian ship which strayed into this zone might be attacked by British nuclear submarines. Fearing this might not be clear enough, on 23 April the British Government clarified what this meant. A message sent to Buenos Aires command via the Swiss Embassy warned the Argentine leaders that any Argentinian ship or plane thought to be a threat would be attacked on sight.

On April 30th the MEZ was upgraded to a total exclusion zone. This meant any ship or plane from any nation that entered the zone could be fired upon. This was unheard of, the Law of Sea Convention (an international agreement that is the framework for international maritime law) had no provisions for such a declaration. Despite this fact, most nations agreed to respect it.

As tensions rose the Argentine military junta refused to back down. The Argentinian Navy was ordered to surround the islands but stay clear of the new exclusion zone. Then on May 1 Admiral Juan Lombardo ordered all Argentinian naval ships to seek out British forces and prepare for a “massive attack” the following day.

Unfortunately for Argentina, British intelligence intercepted the message. The following day Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her War Cabinet met to discuss the issue. It was decided that the Belgrano posed an imminent threat to the lives of British sailors and that the rules of engagement could be altered. Despite the fact that the Belgrano was not within the exclusion zone, it had been seen approaching the zone at speed several times and it would be attacked.

On May 2 the British submarine Conqueror launched three 21-inch Mk 8 mod 4 torpedoes at the Belgrano. Two out of the three had the desired effect and within twenty minutes the Belgrano was being abandoned.

- Wartime Sabotage in a Neutral Country? The Black Tom Explosion

- The Philadelphia Experiment – What’s the Real Story?

Argentina initially declared that over 1,000 Argentine sailors lost their lives that day. In fact, 772 men were rescued and 323 lost their lives. This was the largest number of casualties in a single day during the Falklands War.

War Crime or Necessary Evil?

At the time the sinking of the Belgrano was hugely controversial and has remained so to this day. The argument for the idea that it was a war crime is relatively simple. The Belgrano was outside of the exclusion zone and had not visibly done anything to suggest it was preparing for an attack.

The Argentine government went as far as to state that the Belgrano had been moving AWAY from the exclusion zone, not towards it. Add to this the fact that the exclusion zone was legally dubious in the first place and it would be easy to label the attack unprovoked. Even some politicians within the UK, like the Labour MP Tam Dalyell, agreed with this viewpoint.

On the other hand, Argentina started the war in the first place with an unprovoked attack. Arguably, the Brits were right to be a little paranoid. They had also warned Buenos Aires nine days before the sinking that they would potentially attack ships outside of the exclusion zone if they deemed them a threat.

The Brits also had solid evidence that Argentina was planning an attack on the day of the sinking. So rather than being unprovoked, was it pre-emptive?

For the most part which side of the fence you fall on regarding this issue probably relies on your feelings on the war as a whole and whether it was justified. The Brits were either just defending what was theirs, or were tyrannical colonialists.

But interestingly the Argentine Navy doesn’t see the attack as a war crime. The Belgrano’s captain, Captain Bonzo stated, “It was absolutely not a war crime. It was an act of war, lamentably legal.” He also went on the record as saying the Belgrano was maneuvering ready for the planned attack, not sailing back to Argentina. The Argentine navy has repeatedly agreed with him, stating the attack was not a war crime.

Of course, Argentinian politicians to this day disagree, as do some British politicians. The matter will likely never be settled and will always be a point of contention between the two nations. War crime or not, any death during wartime is lamentable.

Top Image: Hit by British torpedoes, the ARA General Belgrano sinks. Source: Martin Sgut / Public Domain.