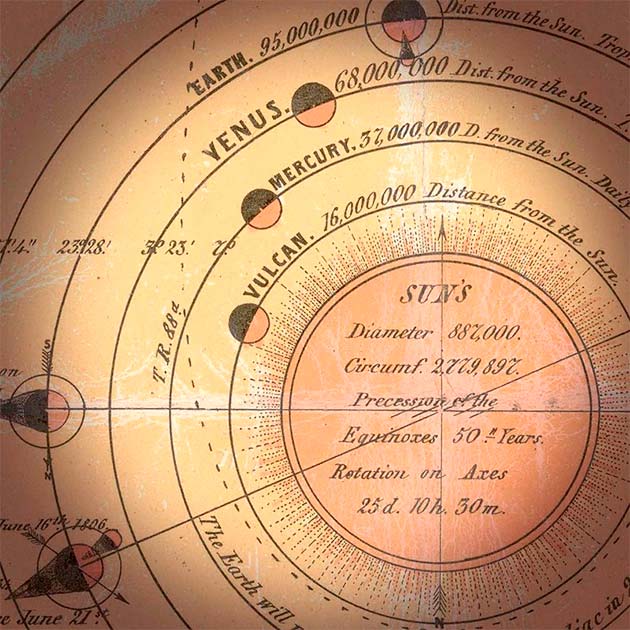

Vulcan! The Roman god of the Forge (and definitely not a direct copy of the Greek Hephaestus, definitely) would be an apt naming choice for a planet close to our sun. Indeed you may wonder why the name Mercury was chosen for that closest and hottest planet of the inner solar system.

Mercury was so called because of the errant path it traced across our sky, but those who would name such a planet Vulcan are in good company. It seems that there was once a planet Vulcan, observed by astronomers and closest of all to our star.

People saw it, described it, and made predictions about its movement across the face of the sun which turned out to match these observations. From 1859 to 1919 we watched the skies and were fully convinced that this planet was out there.

We knew a lot about Vulcan, and yet today we know that no such planet can be seen. What happened to Vulcan?

What was Vulcan?

The Vulcan we observed was between Mercury and the Sun, the nearest planet to our star in the solar system. For 60 years, even the most knowledgeable astronomers thought that Vulcan really existed.

But, in truth, the stories of the planet stretched back much further: for almost 400 years we ave speculated about such a planet. It would ultimately take a theory by Einstein, almost by accident, to prove that Vulcan did not exist, and never had.

- Is There Life on Mars? NASA’s 60-Year Quest

- Outrageous Astronomy – Who Was Behind The Great Moon Hoax of 1835?

The start of the theory came from a man named Urbain Le Verrier, a French mathematician and astronomer. Le Verrier had just discovered Neptune in our outer solar system, using eccentricities in the orbits of other planets to calculate the gravitational pull of Neptune, and hence its position.

Now, Le Verrier had found another wobble, this time in Mercury’s path. Mercury wobbled when it circled the orbit around the Sun. Something hidden, Le Verrier said, was exerting a gravitational influence on Mercury. This would be Vulcan.

In honesty, this solved a lot of astronomical problems. It cleared up the anomalous observations of Mercury and fitted the available mathematics in a pleasing fashion. It seemed only a matter of time before Vulcan was clearly observed: Le Verrier, after all, had told everyone where to look.

There were still problems. The planet, if it existed, would be very close to the Sun, and that would make it difficult to see. Most of the time, the planet would be outshone by the Sun’s light, making it impossible to observe it.

It was obviously not possible to look directly at the Sun and observe the planet because then it would damage the equipment and the observer’s eye. Neither was there advanced equipment for space observation as we have now, so it was very difficult to see the Sun and the proposed Vulcan.

However, never dismiss human ingenuity. A man named Edmond Lescarbault overcame these problems, producing an image of the sun reflected on a flat surface. And there, right where Le Verrier said it would be, was Vulcan.

Edmond Lescarbault was a keen amateur astronomer. However, he did not know he would stumble upon the proof of Vulcan’s existence. In 1859, when he was looking at the sky, he observed a dot on the Sun’s disk. Edmond was at first in doubt because it could be a sunspot instead of a planet.

- Proxima B: Could Aliens Live Around Our Closest Stellar Neighbor?

- Boötes Void: What is This Patch of Space With Few Stars?

However, he returned after some time (attending a patient of his) to the telescope and refocused on the same area of the sun disk to see that the spot had moved quite a bit. It is said that he continued his observation and found that the spot kept moving. The sunspot kept moving until it fell off into the black sky, showing that it could be a planet.

There was a possibility that the moving dot was Mercury when it was very close to the Sun, but Edmond dismissed that it could be Mercury because he had earlier observed the transit of Mercury in 1845, and it was not the same one. Edmond started speculating if he had discovered a new planet and what it was, Vulcan.

Edmond wrote a letter to Le Verrier since he was the one who proposed Vulcan at first. Le Verrier was so excited that he immediately set off to visit Edmond, arriving unannounced. As the theory of Vulcan’s existence was almost proven, Edmond calculated the orbit of the planet, and although it was elliptical, because of its angle with the Sun, it would be almost a circle.

The planet Vulcan was calculated to orbit the Sun every 19 days and 17 hours. The data and circumstances of Vulcan were considered to be proven beyond any doubt, and so Le Verrier officially announced the news of Vulcan’s existence in the solar system. Edmond Lescarbault was given the highest French honor as a reward for discovering the planet Vulcan.

Le Verrier was celebrating the discovery of such a rare planet in the solar system. However, it was not yet clear that Vulcan really existed because observing it was so difficult. In the future, there would be many unidentified reports of the sightings of Vulcan. More data was collected, but it lacked substantial evidence.

It is said that Le Verrier even played around with the data to prove that Vulcan really existed. Even during a total solar eclipse, the planet was not observed for many years, and the scientific community was growing doubtful about the existence of Vulcan in reality.

Only much later was the truth uncovered. From 1905, Einstein’s new theories of modern physics explained the anomalies in Mercury’s orbit without the need for another planet. In fact, these new calculations completely precluded the possibility of Vulcan.

And just like that, the myth of Vulcan was completely debunked.

Top Image: Mercury (center left) transiting our Sun. Vulcan was believed to be even smaller and closer than this. Source: David Hajnal / Adobe Stock.

By Bipin Dimri