In the rugged hills of West Virginia, a clash of power and determination unfolded, forever etching its mark on American labor history. It was the Battle of Blair Mountain, a titanic struggle between coal miners yearning for justice and the mighty forces that looked to suppress their rights.

Amidst the echoing blasts of dynamite and the crackling gunfire, this epic conflict unfolded, revealing the immense courage and sacrifice of those fighting for fair treatment. It was a turning point that challenged the oppressive grip of corporate interests, igniting a fire of change that would shape the destiny of the working class.

A Long Time Coming

The Battle of Blair Mountain was a massive labor uprising and the largest armed rebellion America had seen since the Civil War. It took place in Logan County in West Virginia and was a major event in what became known as the Coal Wars, series of similar labor revolts all centered in the Appalachia region in the early 20th century.

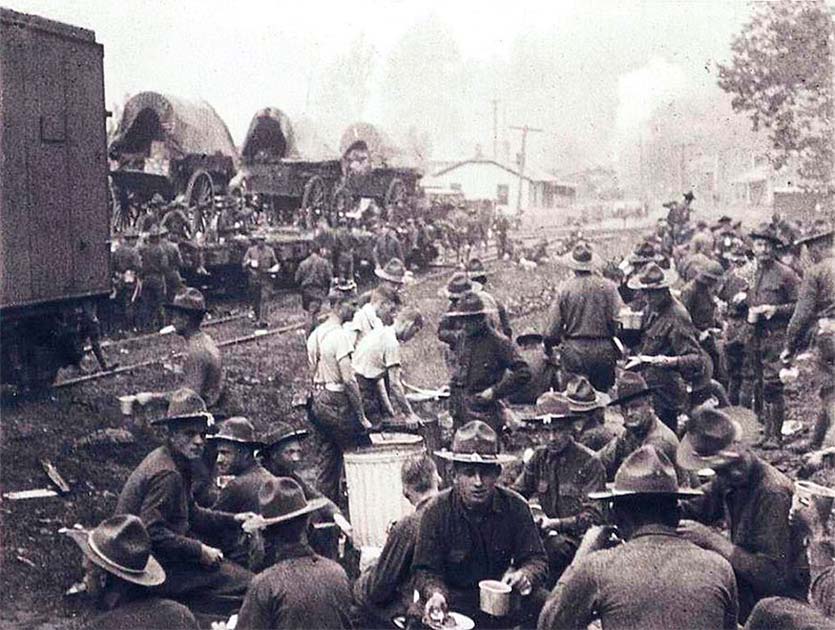

The Battle took place over five days between late August and early September 1921 and saw the deaths of up to 100 people. But despite its relatively brief duration, this was no simple strike or protest. Over 10,000 coal miners, most of them armed, took on 3,000 lawmen and “strikebreakers”.

Neither side pulled any punches, and it has been estimated that by the time the dust had settled over one million rounds had been fired. It took the West Virginia Army National Guard led by William Eubanks stepping in at the order of the president, Warren G. Harding, to calm things down.

So, what led to this armed uprising? Well, this is American labor history, so of course it’s about people trying to unionize. The United Mine Workers Union was formed in 1890 in an attempt to get miners fairer wages and better working conditions. This, unsurprisingly, was thought unacceptable by many mine owners.

Following the union’s creation, the coal mines of Mingo County, West Virginia announced that they would only employ non-union workers. Miners were forced to sign contracts that said if they did ever join a union, they would be immediately fired.

Since most miners lived in company towns (towns where everything from the houses to the shops and even schools are owned by the company), losing their job basically meant losing everything. They were trapped by a system over which they had no control.

For over thirty years mine bosses held out against the evils of fair wages and safe working conditions. Finally, in 1920, the UMW’s president, John L. Lewis, decided it was finally time to fight back.

- The Boxer Rebellion: When China Found Her Freedom?

- Dictator by Default? Syngman Rhee and the South Korean Elections

His motivation came as much from keeping his own job as siding with the workers however. Under pressure from miners in other parts of the country who had held a massive strike in 1919, as well as the owners of unionized mines who were being undercut by West Virginia’s nonunion mines, Lewis knew his presidency was at risk if he didn’t do something.

Big names like Mother Jones, an important labor organizer of the time, and Frank Keeney, president of the local union district, visited the workers to give fiery speeches. This push worked and 3,000 Mingo Country miners risked their jobs by joining the UMW. They were all promptly fired.

To prove a point the mines then hired agents from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to evict said miners and their families. They were less a detective agency and more a gang of thugs who enjoyed cracking skulls and firing on crowds.

The agents arrived in Matewan, Mingo County on May 19, 1920. These agents had been responsible for the Ludlow Massacre of 1914, which had also been part of the Coal Wars. They tried to bribe the local mayor, Testerman, to allow them to place machine gun nests on roofs in the town but thankfully the Mayor refused.

The agents, 13 in total, headed from Matewan to the Stone Mountain Coal Company property. They began evicting union members’ families at gunpoint, throwing their few belongings into the road where they were soaked by the heavy downpour of rain. Furious miners saw the abuse and ran to town to report the agents’ actions.

The agents were stopped from leaving town by the local police chief, Sid Hatfield, and some deputized miners. When Hatfield tried to arrest the agents, they in turn revealed a phony arrest warrant for the police chief.

The local mayor was called to cool things down but when he sided with his chief, a gunfight broke out. Ten men were killed including mayor Testerman, and the two lead agents, Albert and Lee Felts.

A Hero will Rise

This gunfight, known as the Matewan Massacre, was a major event in the run-up to the Battle of Blair Mountain. Police Chief Sid Hatfield became a hero, proving that the Baldwin-Felts agency wasn’t invincible. Throughout the summer of 1920, more and more mines in Mingo County joined the cause and unionized.

Of course, the coal operators countered by bringing in even more union busters. Throughout the summer and fall of that year, there were sporadic shootouts between miners and the busters. As things grew increasingly violent State police were brought in to take down a miner tent colony near Williamson which led to another shootout. The fact State police were involved told the miners whose side the state was on.

From there things only deteriorated. Chief Hatfield was charged with the killing of the agents and union miners began launching organized assaults on non-union mines in rebellion. As the state sided with the mine owners, miners increasingly turned to guerilla tactics.

- Elizabeth Barton: The Nun who stood up to Henry VIII

- The Battle of Gettysburg: How the Civil War was Won

On August 1, 1921, Chief Hatfield, hero of the rebellion, traveled to McDowell County for his trial. As he walked up the courthouse stairs he was assassinated by a gang of Baldwin-Felts agents. The miners were rightly outraged and began arming themselves, knowing the agents wouldn’t face justice.

On August 7, 1921, the UMW called a rally at the state capitol in Charleston. Union leaders met with the state governor, Ephraim Morgan, with a list of demands. The governor rejected the demands, leading to the miners becoming even more restless.

Thousands of coal miners, armed and organized by the UMW, marched towards Logan County, where the anti-union forces were concentrated. They aimed to support the miners in that area who were already on strike.

The miners met opposition from the coal companies’ private armies and local law enforcement. The ensuing conflict lasted for about a week, involving gunfire, dynamite explosions, and aerial bombings.

A Lesson from History

The battle ended when the US Army, under orders from President Warren G. Harding, intervened and restored order. Although the miners were ultimately defeated, the Battle of Blair Mountain marked a turning point in labor history.

It brought attention to the plight of coal miners and the need for labor reforms. The conflict highlighted the extreme wealth inequality, exploitation, and brutality faced by industrial workers.

In the aftermath of the battle, public opinion started to shift in favor of labor rights and unionization. It led to increased scrutiny of the coal companies’ practices and eventually contributed to improvements in labor laws and regulations. The battle also played a role in the decline of the coal industry’s influence over West Virginia politics.

As the dust settled over the scarred battleground of Blair Mountain, a resounding message echoed through the hills—a call for justice that could not be silenced. Though the immediate outcome may have seemed like a defeat, the Battle of Blair Mountain sowed the seeds of change that would blossom in the years to come.

It gave birth to a resilient spirit, fueling the fight for workers’ rights and reshaping the destiny of the labor movement. The legacy of those brave miners endures, reminding us that in the face of adversity, unity and unwavering determination can shake the very foundations of power and forge a brighter future for all.

Top Image: Newspaper headline on the developing situation in the Battle of Blair Mountain. Source: The Washington Times / Public Domain.