There are secrets in the ground which surrounds Govan Old Parish Church in Glasgow, Scotland. Since the 1950s, strange carved stones have been found in the area in and around the graveyard, itself an extremely ancient burial place.

What was found means the church is now the home to one of the most significant collections of Viking carved stones that can be found within the United Kingdom. And artifacts continue to be found, with more stones that were hidden beneath the turf discovered just this year (2023).

Why are these stones here, and why was this place so special? New connections are slowly being formed between the church, the community, and its archaeological treasures.

History of the Stones

Approximately 1,000 years ago, Govan was an important religious center for the medieval kingdom of Strathclyde. This is evidenced not through written records that have been left, as there is none surviving, but through the archaeological record which has shown that there was a significant religious site here.

There have been a large number of elite burials found here, all adorned with ornate grave markers. It is a sign of the wealth and artistry of the period.

The site was first discovered in the 19th century when a dozen or so carved stones were excavated, made the subject of plaster casts, and documented by Thomas Annan. Annan was a photographer known for documenting the living conditions of Glasgow’s poorest areas. These documents have been invaluable for modern researchers.

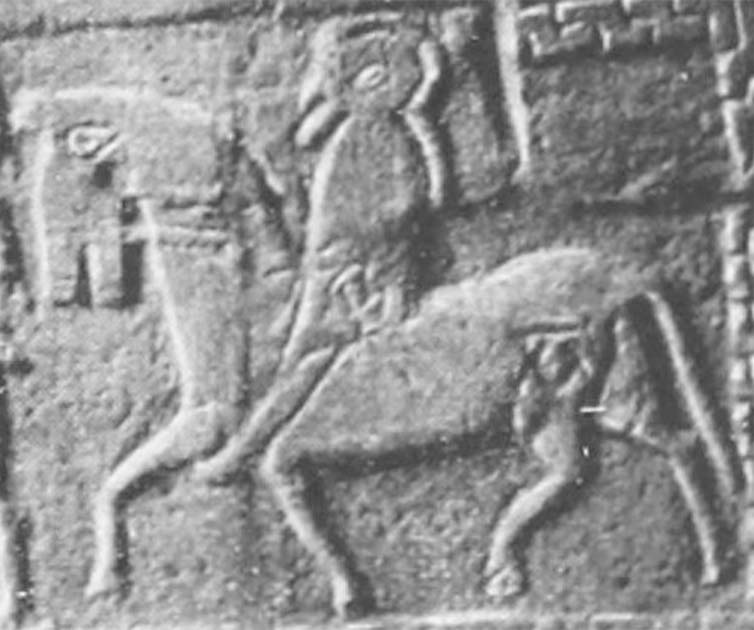

It has been estimated that around two-thirds of the stones were brought into the Victorian parish church in Govan, and it is here where they still remain today. They became collectively known as the Govan Stones and compromise of a sarcophagus with carved animals, five gravestones known as “hogbacks” (distinctive house-shaped stones found mostly in Scandinavian and Northern English settlements), two upright cross-shafts, two cross-slabs and around 21 stones that had been laid horizontally to cover graves.

All 21 of the stones were adorned with intricate patterns and crosses. There were also 14 more that could not be displayed in the church and so they were placed on the Eastern boundary wall of the churchyard.

The church acts as a reminder of Govan’s former prosperity and power. Albeit this is more accurate for recent times. The Clydeside, where Govan is situated, was once the parish of the world-leading shipbuilding industry of Glasgow and the British Empire.

It had a thriving population and thus needed a church that would be big enough to fit all of the congregation. From records, it has been suggested that at its height, the Govan church had a congregation of 1,300.

The church itself also remains a nationally significant example of Scottish Gothic Revival architecture with some of the finest stained-glass windows of the age. It was designed by Sir Robert Rowand Anderson, a leading architect who also designed the University of Edinburgh and the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

As Govan thrived, the church became surrounded by shipyards and workshops. Despite this, the church was able to maintain its traditional borders. Unfortunately, 14 of the Govan stones were lost when, in 1973, the adjacent Harland and Wolff shipyard was demolished. It is unclear whether they were destroyed in the process or lost under the rubble. They remained buried for half a century.

The Churchyard

By the 1990s, Govan was a different place. It was besieged by a decline in the post-industrial period and the area faced significant unemployment and depression.

The parish church was keen to boost the community’s pride and so tried to engage with the distant past of the area. The church sought help from the University of Glasgow and in an excavation led by them, they uncovered burials dating to the 5th and 6th centuries.

The churchyard itself was also discovered to have a distinctive teardrop shape, itself an indication of how old it was. By following this shape, the team was able to uncover the original boundary ditch.

Since 2007, the churchyard has been decommissioned by the ecclesiastical organizations. Excavations have continued throughout though, and the local community sprang behind the church in order to support the excavations taking place there.

- Thick Skinned: Why Did Vikings Really Cover Their Shields with Leather?

- The Painted People: Why Did the Picts Disappear?

This action formed the Govan Heritage Trust which is a community-based charity that still owns the church and its churchyard. Due to the legislation in Scotland, the investigations have to be non-invasive by nature. This means that there are no full excavations taking place. Instead, the team is deployed in 5m x 5m (16’ by 16’) squares to scan the area with iron probes to see if anything lies beneath the surface.

Vikings in Scotland

The stones have been dated to at least the 9th century. This was a time when the Vikings were prolifically raiding the Clyde region and the surrounding territories.

In the written source, the Annals of Ulster from Ireland, they claim that Dumbarton Rock was destroyed in 870AD which was not far from Govan or the church. It was the center of the ancient kingdom of Britons and was known as Alt Clut. After this destruction of Alt Clut, the Brittonic King, Artgal, was either killed or enslaved by the Vikings. From here, the Vikings moved up the river to Govan in order to strengthen their strategic position.

The presence of the hogback stones indicates that the Vikings must have settled in Govan at least partially. The stones are designed to resemble Scandinavian longhouses and were found mostly in that region. Professor Stephen Driscoll from the University of Glasgow claims:

“It underpins this idea that the British kingdom of Strathclyde has some strong connections with the Scandinavian world. My feeling is that this is meant to represent a lord’s hall or a chieftain’s hall”.

The sarcophagus that was found and that has become the centerpiece of the Govan Old Parish Church stones is thought to commemorate St Constantine. He was the son of the Pictish King Kenneth Macalpine and fought bravely against Viking invasions in the 9th century.

The carvings on the sarcophagus feature a stag hunting scene as well as stylized animals. It was carved from solid sandstone and is the only one of its kind in Pre-Norman and Northern Britain.

Top Image: The shape of the Govan Stones resembles the long hall of a Scandinavian chieftain. Source: JoeDerrySetch / CC BY-SA 4.0.

By Kurt Readman