“Crossing the Rubicon” is, if not a common phrase, something recognizable to most. It captures a moment of decision, a point of no return for better or for worse, but why did it come to mean this?

The Rubicon itself is even mysterious. It is believed to be a small river that separates the province of Gaul from the heartlands of Roman territory. General Julius Caesar crossed it on the 10th of January, 49 BC, which was fine. But he brought his army with him, which was not.

It is termed his moment of decisiveness because his crossing the Rubicon was expressly forbidden in such terms. Caesar’s army, inevitably loyal to him after he had brought them glory and victory in Gaul, could be a threat to the Republic

As per the Roman Republic law, if any provincial governor leads an army across this stream, they will be declared a public enemy. Thus, the act was considered a declaration of war. Why did Caesar do it, and did he see the far-reaching consequences of his actions?

The Rubicon

The Rubicon is a shallow river within northeastern Italy, near Rimini. It was also known as Fiumicino and it was only in 1933 that it was identified as the Rubicon that Julius Caesar faced in 49 BC. This river itself is nothing special, flowing around 50 miles (80 km) to the Adriatic Sea from the Apennine Mountains.

Why did he face this question? It was all part of the system, and particularly the politics of the Roman Republic. Julius Caesar had been appointed as governor of Gaul, which included some of northern Italy and the river itself.

Such positions came with immense power, power enough for the right man to threaten Rome herself. These risks were well recognized, and at the end of his governorship, the Roman Senate passed an order for him to disband all of the members of his army and return to Rome immediately.

But Caesar didn’t listen to the Senate. He saw a crisis in Roman politics, and most likely he saw an opportunity for lasting power. He was trusting on the loyalty of his troops, for technically by crossing the Rubicon at the head of an army his imperium (right to command) was forfeit, as was life.

Caesar was very well aware of the consequences of his insubordination. He knew that his act would give rise to a civil war between the Roman ruling class and him.

At the time, the Roman nobility was led by one of Caesar’s strongest former allies and opponents, Pompey the Great. Pompey was an excellent military leader and commander, and Caesar knew that if he crossed the Rubicon, it would lead to conflict between the two.

Caesar didn’t let anyone know about how he was about to disobey the Senate’s call. In secrecy, he ordered his army to proceed to the river banks and wait. Later, after dinner, he excused himself and left early. He boarded a chariot drawn by mules from a nearby bakery shop. There was a certain delay in locating the troops, but finally, Caesar found his army to join them.

He headed South and defied the Senate’s instructions. When he reached the Rubicon, he thought about two possible choices right in front of him. He could abandon the idea and head back or continue with the war-triggering decision.

Crossing Rubicon was a symbolic and literal act of no returning and a war act against the Roman Senate and Pompey. Thus, this was the place and time where he made the most agonizing choice and decided to press on.

What Happened Next?

The purpose of initiating the law of considering crossing the Rubicon as treason and an offense punishable with the death penalty was to protect the Roman Republic from any form of internal military conflict. When Caesar crossed the Rubicon, he revealed his true aspirations, and the course of history altered forever then after.

While he stepped into the Rubicon, he declared Iacta Alea Est, a Latin phrase that translates as “Let the die be cast.” There is more in this phrase than you would think: mighty Caesar was a gambler, for sure, but what he meant is that dice are made to be cast, and that to not do so is to fall short of expectations.

It triggered a civil war, just as expected, and Caesar’s power play led to him being declared “dictator” to bring order to the subsequent chaos. It also cost Caesar his life 5 years later, stabbed for death for drawing too much power to himself.

Caesar gambled that he would not just defeat Pompey but also overthrow Cato, Cicero and other such politicians. In this his shrewd judgement did not desert him: Rome was caught off-guard and the arrival of Caesar’s legion in Italy proper caused a sudden panic.

Caesar then marched to Rome with his entire army and took control of its government. He took over the treasury and announced himself as the dictator. Pompey, the commander of the Roman Navy at that time, retreated and moved to Greece.

This action by Caesar led to a civil war that lasted for around five years. He also defeated Pompey in a consistent series of ferocious land battles across various places of the Roman Empire within the period of four years since he took charge.

He defeated him once in Greece, leading a winning campaign in Iberia. Later, Pompey fled to Egypt to Ptolemies, but they refused to offer shelter to some losers. They executed Pompey by cutting off his head.

Hence, Caesar became the unchallenged leader of the Roman Empire. He also said that it’s important he survives for the state. He also said that if anything happened to him, Rome wouldn’t survive in peace.

A Phrase from History

The phrase “Crossing the Rubicon” is therefore apt for a decision from which there is no escape. Caesar himself did not see the far reaching impact of his decision, of that we can be sure. His actions led to the accession of his nephew and heir Octavian to become Augustus, first to use the honorific “Caesar”: emperor in his stead.

The Roman Republic never recovered from Caesar’s decision. From this point on Rome was at the head of an empire, and the Roman Republic was gone.

Arguably, this led to the fall of the Roman Empire, as well. Rome would expand her territories enormously in the centuries that followed the crossing of the Rubicon, but her fall in the 5th century was hastened by poor decisions from her Caesar.

Such is the trap of hereditary systems, empires and kingdoms, and all those who wish for the “benevolent dictator” fallacy. Unless you choose your leaders, eventually they will fail you. Brutus saw that, although minting coins to celebrate stabbing Caesar to death was perhaps a little much.

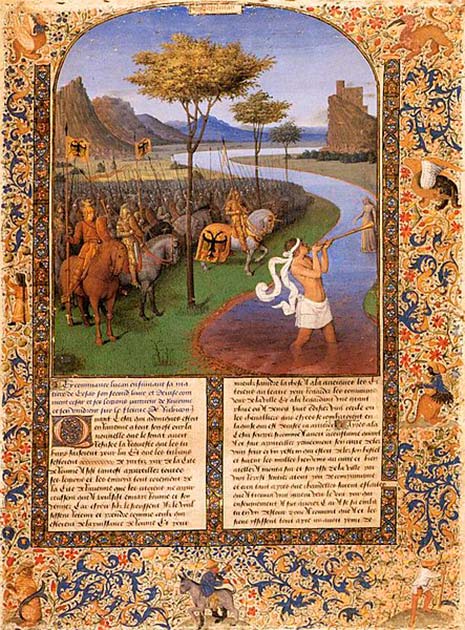

Top Image: Caesar crossing the Rubicon. This 1875 painting, blessed with hindsight, shows the momentous decision Caesar is making, although the artist may have got a little lost in symbology. Source: Adolphe Yvon / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri