Nestled beneath the icy expanse of the Greenland ice sheet lies a chilling reminder of Cold War ambition and secrecy: Camp Century. Established in 1959, this covert military installation served as the clandestine hub for Project Iceworm, a top-secret United States Army program.

Its public designation as a scientific research facility was in part a masquerade, for Camp Century harbored a far more ominous purpose: to house and support the deployment of nuclear missile launch sites beneath the Arctic ice. As tensions between superpowers peaked, this audacious endeavor exemplified the lengths to which nations went to secure strategic advantage in the frigid depths of the Cold War.

Nuclear Secrets and Hidden Tunnels

Project Iceworm was the very definition of top secret. While it was initiated in the late 1950s and properly got underway around 1960, its existence was only officially confirmed in 1996 with the release of declassified government documents. It was from these that the public finally learned the truth about the project and its cover, Camp Century.

Set in motion by the US Army, Project Iceworm’s primary objective was to deploy a network of mobile nuclear missile launch sites under Greenland’s ice sheet. The idea behind it was to enhance America’s nuclear deterrent capabilities against the Soviet Union.

The project was conceived during the height of the Cold War, and it aimed to establish a covert infrastructure capable of launching intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) from within the Arctic region. It was in essence a secret nuclear base, hidden beneath to ice.

The plan was to have a system of tunnels around 4,000 kilometers (2,500 mi) in length hidden under Greenland. These tunnels would be able to deploy up to 600 nuclear missiles within range of the USSR and would be periodically moved around in case the Soviets ever learned of their existence. The project was top secret, but Denmark’s government was kept in the loop, kind of.

Of course, deploying such a network would not only be a massive engineering feat, but it would also be hugely expensive. The US however felt it would be worth it. Firstly, it hoped if successful the project would help the army to surprise and outmaneuver potential adversaries, complicating their efforts to detect and target American missile installations.

- Project Sanguine: Submarines, and Quite a Lot of Wisconsin

- (In Pics) Six Crazy Military Inventions of the Cold War

Secondly, throughout the Cold War, both the US and the USSR made significant efforts to project power into the Arctic region for strategic, military, and economic reasons. It was hoped that if the Soviets ever pulled ahead in this particular race Project Iceworm could provide a buffer against potential Soviet attacks.

Finally, this was the 50s/ 60s, and both the US and USSR were preoccupied with extending their respective nuclear reaches. Project Iceworm would give the US an advantage in the polar region and augment its overall strategic posture. The more spread out their nuclear reach was, the greater the deterrent.

Camp Century: the Perfect Front

Construction on Camp Century began in 1959 and the camp ran until 1967. When the Americans approached Denmark’s government, they weren’t exactly honest about everything.

They pitched Camp Century to the officials as an attempt to test construction techniques under Arctic conditions and to prove the feasibility of (relatively) cheap ice-cap military outposts. It was also claimed the camp would carry out “scientific experiments” and test the effectiveness of a portable nuclear reactor (the PM-2A).

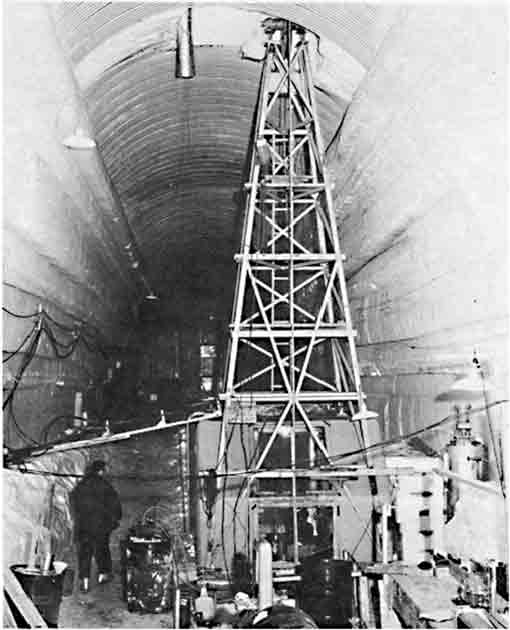

To be fair, the US wasn’t exactly lying. In total 21 trenches with a total length of 3,000 meters (1.9 mi), were cut out of the ice sheet and covered with roofing. No nuclear missiles were installed.

Instead, the tunnels were filled with prefabricated buildings that acted as everything from a hospital and shops to even a theater and church. It was a mini town under the ice with up to 200 researchers and army personnel living there at a time.

The site was indeed also used to test the world’s very first portable nuclear reactor, which provided the site with power from 1960 until 1963. For the most part, the researchers stationed there tested the nearby melting glaciers for germs like the plague and drilled some of the first ice cores. This research was still being used by climatologists as late as 2005.

But in reality all this research was just a by-product of the US government’s main aim. Camp Century wasn’t any old research station. Its primary purpose was to prove that it was possible to dig a network of tunnels under the ice to hide nukes.

The ice cores being dug had less to do with climate research and more to do with making sure the tunnels would remain stable in the long term as the ice sheet shifted. At first, the project seemed a success. So, what happened?

Initially, it did seem that Camp Century had proved Project Iceworm was feasible, but things soon began to change. After around three years it became clear that the ice sheet wasn’t as stable as at first thought. In reality, snow and ice are viscoelastic, which means they move and deform over time.

The US had underestimated how quickly this process happened and the geologists stationed at Century found that in all likelihood the camp had about two years until its tunnels would begin to collapse. They were proven right when in 1962 the ceiling of the camp’s reactor room began to buckle and had to be lifted by 5 feet (1.5 m) to avoid damaging the reactor.

This raised safety concerns and in July 1963 the army decided to shut down the reactor for good and make Century a summer-only camp. In 1965 the reactor was removed, and the camp was evacuated.

A year later the project was shut down for good. The government had decided that with the rate the ice sheet moved Project Iceworm was no longer a possibility.

The Ghost of Project Iceworm

Unfortunately, they didn’t do a great job of shutting Iceworm or Camp Century down. When the camp was decommissioned in 1967 most of it, including its waste, was simply abandoned under Greenland’s ice sheet. It was believed that it would stay there, safe and sound under tons of permanent ice and snowfall for the rest of time.

- Project Azorian: Did Howard Hughes Try to Steal a Russian Sub?

- Did the CIA Really Have an Inflatable Plane?

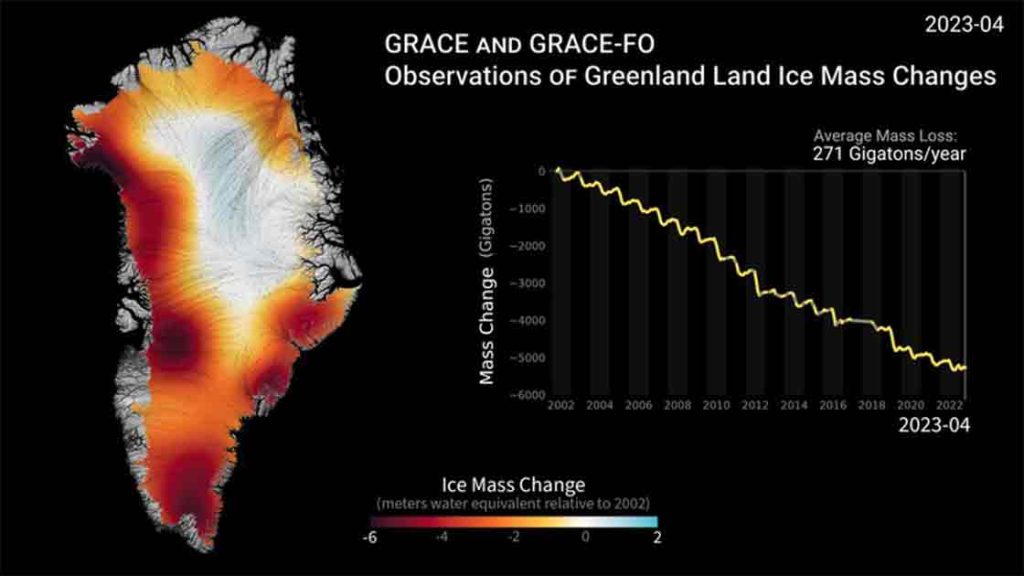

A lot has changed since the 60s, however: namely we understand a lot more about climate change now than we did then. A 2016 study found that over the next few decades, Greenland’s ice sheet will begin to melt.

It’s feared this will begin to release the waste abandoned at Camp Century. This means nuclear waste, 200,000 liters of diesel, PCBs, and an unpleasant amount of sewage will be exposed to the local environment. While estimates vary it is thought that as early as 2090 or as late as 2179 all this waste will be revealed, damaging an already at-risk habitat even further.

Politically, the camp’s existence and true purpose led to somewhat of a chilling in relations between the US and Denmark in the 90s. Following the release of classified info in regard to a B-52 bomber crash at the American Thule Air Base (another American installation close to Camp Century) the Danish Foreign Policy Institute decided to look into other lies Denmark’s parliament and the US might have told over the years.

This investigation led to the truth behind Camp Century being revealed, Misleading one’s allies is rarely a good look.

But ultimately, looking back Project Iceworm can be seen as an ambitious experiment whose ultimate demise underscored the formidable challenges posed by the Arctic environment and the complexities of maintaining covert military infrastructure. Even the United States, with all its technology and resources, couldn’t stand against the forces of Mother Nature.

It also stands as a chilling reminder of the lengths to which nations went during the Cold War to get one over on each other. Today we are still paying the price for these efforts and the remnants of Camp Century are proof that we will continue to pay for decades to come.

As the world reflects on this chapter of history, it serves as a cautionary tale of the enduring consequences of the Cold War’s icy grip.

Top Image: Trench construction begins in 1960 at Camp Century, secret home of Project Iceworm. Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory / Public Domain.