The Houston Riot of 1917 was a pivotal moment in American history, although one sometimes lost amidst the trauma and destruction of World War I when considered today. This is not an easy story, but it is invaluable for the light it sheds on the complex dynamics which underlay race relations in the United States, a century ago.

Often overlooked in historical narratives, this event has garnered increasing attention in recent years as scholars and activists delve deeper into its significance. For many years, the black soldiers of the 24th Infantry Regiment were painted as villains but over the years a new narrative has emerged.

The picture that emerges is one of a riot sparked by racial tensions, mistreatment, and systemic injustice within the US military. Who is culpable for the tragedy that unfolded?

When Racial Tensions Reach Boiling Point

On July 27, 1917, the United States Army ordered the 3rd Battalion of the all-black 24th Infantry Regiment to be transferred from Columbus, New Mexico to Houston, Texas. With the US having recently joined World War I the War Department had announced the construction of two new military installations in the area. The 24th were to guard the construction of one of them, Camp Logan.

It didn’t take long for problems to arise. Houston at the time was strictly segregated and Jim Crow laws were still in place. The newly arrived soldiers found that their accommodations were segregated as were their drinking facilities. Suffice it to say these men, who were serving their country, were less than pleased and weren’t afraid of expressing their displeasure.

Things got worse when the local police, the Houston Police Department, began targeting the newly arrived black soldiers. Around lunchtime, on August 23, 1917, two HPD officers decided to disrupt a gathering of young black men (who were playing craps according to some reports) in Houston’s mostly black San Felipe district. The two officers fired their guns into the air and when the men scattered, gave chase.

One officer, Sparks, barged into the home of a local black woman, Sara Travers. Despite finding none of the suspects in the woman’s home he marched her outside and put the innocent woman in handcuffs.

From there, things escalated. As Sparks and his accomplice, Officer Daniels, were calling in their arrest at a nearby patrol box, Private Alonzo Edwards of the 24th Infantry Regiment approached them and offered to take custody of Travers.

While the two officers later denied any wrongdoing towards the woman, Edwards raised concerns as to how she was being treated. The two policemen responded by pistol-whipping him and arresting the private.

- The Camp Van Dorn Slaughter: Were 1,200 US Soldiers Executed?

- The Battle of Blair Mountain: Unleashing the Workers’ Revolution

Later that day military police officer Corporal Charles Baltimore saw the two policemen and inquired as to his comrade’s status. They answered by pistol-whipping him too and firing their guns into the air.

Baltimore ran away but was soon found hiding under a bed in a nearby house. He was beaten by the officers and arrested. It had been a busy day for two of Houston’s most racist policemen.

News spread to Camp Logan that Baltimore had been murdered by the two policemen. Just as the men of the 24th were reaching a fever pitch an officer brought in an injured but breathing Baltimore. This calmed the men, for the time being.

The Riot

Things didn’t stay calm for long. Not long after Baltimore’s return, the soldiers heard reports that a white mob was about to descend on their camp. Trying to keep things peaceful their commander, Major Snow, revoked all passes for that night and ordered for the guard around Camp Logan to be increased.

Despite his precautions later that evening, he found a group of his men searching for arms in one of the supply tents. He ordered all of his men to assemble and told them it would be, “utterly foolish, foolhardy, for them to think of taking the law into their own hands.” Sadly, his words fell on deaf ears.

One of the soldiers had managed to sneak his rifle into formation and fired it once, crying that the mob was about to burst in. Chaos broke out and the soldiers began raiding the supply tents looking for weapons to defend themselves with. They quickly found the rifles and ammunition they were searching for.

Fear turned into hatred and the now-armed men began shooting randomly into the camp’s surrounding buildings. After a few minutes of chaos at Camp Logan (its white battalion commander had already fled) a new leader, Sergeant Vida Henry seized control. He ordered the men in the area, around 150, to prepare for a march on Houston.

Vida Henry led his men through the neighborhoods surrounding the camp and ordered them to fire on civilian buildings with outdoor lights. At one point two cars drove past – one full of white occupants, the other black. The car carrying white civilians was fired on.

In total the group marched nearly 2.5 miles (4 km) until they reached the San Felipe district. It was here they finally met police resistance. Luckily for them, the HPD was completely unprepared and hadn’t expected the black soldiers to be armed or put up much of a fight. Two policemen were killed and a third later died from his injuries.

The soldiers carried on their march until they ran into an open-topped car transporting a man in an olive-drab uniform. Believing him to be a policeman, they fired, killing him instantly. The man was Captain Joseph W. Mattes of the Illinois National Guard.

Upon realizing this the rioters began to panic as the reality of what they had done hit home. The consequences for black men killing not just a white officer but civilians too would be dire. The group quickly disbanded, with just a few marching back to Camp Logan with a terrified Sergeant Henry.

Upon returning to base Henry informed his men that he planned on killing himself after they left. His body was found the next day. His skull had been crushed and he had been stabbed in the shoulder with either a bayonet or knife. Whether by his own men or someone else is unknown.

By the time the dust settled 17 were dead. The casualties included four police, two soldiers, and nine civilians. Over the following days more would succumb to their injuries, and the death toll would continue to rise.

Repercussions

By the next morning, Houston was under martial law. The soldiers who hadn’t flown were rounded up and disarmed. Many of those who had tried to escape were found hiding during a house-to-house- search of San Felipe. Their court-martial was about to start.

In total 118 defendants were represented by one officer, Major Harry Grier. The Major had no legal background and was only given 10 days to prepare. Nobody seemed too concerned, due process wasn’t a priority when it came to black mutineers.

Over 22 days roughly 200 witnesses were brought forward to testify and testimonies covered more than 2000 pages. How accurate the testimonies were is another matter. The darkness and rain that night meant that many of the witnesses struggled to positively ID anyone. There have also been accusations that many of the witnesses had been granted immunity or offered leniency, coloring their testimonies.

It was the largest murder trial in US history. The court-martials ended with 19 soldiers being executed and a further 110 convicted of mutiny, murder, and assault.

Disturbingly, the men who were executed were buried in unmarked graves. Their corpses were found in 1987 at Fort Sam Houston, with the only thing marking their names being empty soda bottles with their names in them.

Over the years, the perception of the Houston Riot of 1917 has evolved from being largely overlooked to increasingly recognized as a significant event in American history. Initially dismissed or downplayed, it is now viewed through a lens that acknowledges its profound impact on race relations and military justice.

As society’s understanding of systemic racism has deepened, the riot is now seen as a poignant symbol of the struggles faced by African American soldiers during World War I. Recently the US Army set aside 110 of the convictions handed down to the Houston rioters.

It was deemed that the men served the military with honor and had been wrongly treated due to their race. After years of civil-rights campaigns, the military also admitted their trials had not been fair. The riot’s commemoration serves as a reminder of the ongoing fight for equality and justice, prompting reflection and dialogue on past injustices and their lingering effects.

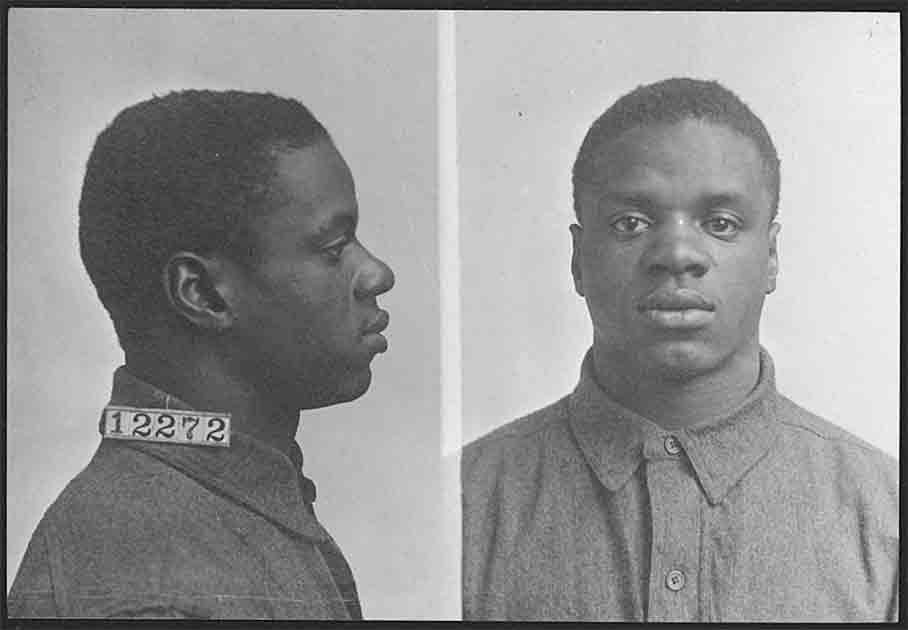

Top Image: The largest trial in US history: members of the regiment involved in the Houston Riot. Source: Unknown Author / Public Domain.