The key moment in Christianity is Jesus’s death on the cross. From this sacrifice the son of God returns after three days, come back to life to reassure the mourning disciples that everything will be fine. He gives them tasks, and then heads off to heaven for ever (or for the moment, anyway).

Taken in isolation, this is a strange sequence of events. Sacrifice is one thing, but this sacrifice is undone within a matter of days. Coming back from the dead is also pretty momentous, but Christ appears to only a handful of people before disappearing semi-permanently. Might as well have not come back at all, you might think.

There is a reason for this, however. The death and resurrection of Christ is an aspect of religion left over from a much older way of thinking. Once we know what to look for, we see dead and resurrected gods everywhere in the ancient world.

And what this repeated story can tell us about the cultures in which it appears gets to the very core of what religion is. Put simply, religion is an attempt to explain what its followers observe but cannot explain, somewhere between metaphor and protoscience.

The motif of a dying and resurrected deity spans across various cultures and religions, symbolizing the cyclic nature of life, death, and rebirth. This archetype reflects humanity’s observations of the natural world, particularly the seasonal cycles of growth, decay, and renewal.

The motif in Christianity is a later version, shorn if its original context and meaning but surviving as a relic of the religions on which Christianity is founded. Earlier Greek, Pagan, and Egyptian traditions all had their versions.

Is it an intriguing aspect of ancient religions? Or is it more, is it the core of what ancient religions were, and what religion, in and of itself, is? Is it universal?

Why Does Christ Come Back?

In Christianity, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ are central to the faith’s doctrine. Christ’s crucifixion, death, and subsequent resurrection are commemorated annually through Good Friday and Easter, symbolizing the ultimate victory over sin and death.

Of course, for modern Christians this has nothing to do with the cycle of nature. This narrative provides believers with hope for eternal life, emphasizing spiritual rebirth and the possibility of redemption.

- Swoon or Substitute? Two Rationalizations of the Resurrection of Jesus

- Sounds Familiar: Deucalion and the Greek Flood Myth

But that isn’t where it came from. The rebirth of a dead god at Easter time, traditionally the moment in a lot of the world when crops start to grow, is an anthropomorphized explanation of the cycle of the seasons. The dead world comes back to life in the spring, and God created the world, so it makes sense that he runs on the same schedule, and that he can bring Himself back to life at the same time.

The modern version of the death-and-resurrection story has nothing to do with this, of course. Centuries of Christian orthodoxy layered on top of the original story means it has transformed into a message about life after death somewhere else, not here on Earth.

The abrupt departure of Jesus after his resurrection allowed Church leaders to paint a vivid picture of where he went, and to make extravagant promises about there.But originally it was not about there, it was about here.

Death and Resurrection in Older Traditions

Perhaps the most well-known example of the death and resurrection story outside of Christianity, at least to those with a smattering of classical knowledge, is that of Hades and Persephone. The story goes that the god of the underworld espied the beautiful Persephone one day and spirited her off to the underworld to be his bride.

In Persephone’s absence her mother, Demeter, mourned. Demeter, a goddess of fertility, neglected her duties to the world of mortals in her grief: crops withered, plants and animals died away, and the very world itself started to come undone.

This worried the gods and Zeus, who knew very well what had happened, sent a message to Hades that Persephone should be returned to her mother. However Persephone had, during her time in the underworld, eaten some pomegranate, and was now partially beholden to that place, too.

And so we have a neat explanation for the seasons. For part of the year Persephone is with her mother, and everything is great: crops grow, the weather is nice, the land is fertile. But when Persephone returns to the underworld and her dark husband, the world dies once again.

Again we have religion explaining what people saw around them in terms they could understand. They knew that crops grow in the springtime and that the world grows cold and dead in the winter, but not why. And it looking to personify the natural cycle they gave it a name: Persephone.

Now you could argue that Persephone doesn’t actually die, she just goes to the underworld for part of the year before returning to life. But the underlying metaphor is the same, and for the Greeks dying and going to the underworld were essentially equivalent, rendering this point somewhat moot.

We see this in other pagan rituals, too. Festivals such as Beltane celebrate the themes of fertility, renewal, and rebirth. Beltane, which marks the beginning of summer, is characterized by rituals that symbolize the potency of life and the growth of the natural world. It is the rebirth of the god Bel, dead for a season but now back with all his life-giving power.

Fires are lit to represent the return of light and warmth, mirroring the sun’s increasing strength. These celebrations are a direct homage to the life-death-rebirth cycle, emphasizing the importance of seasonal changes in the regeneration of life.

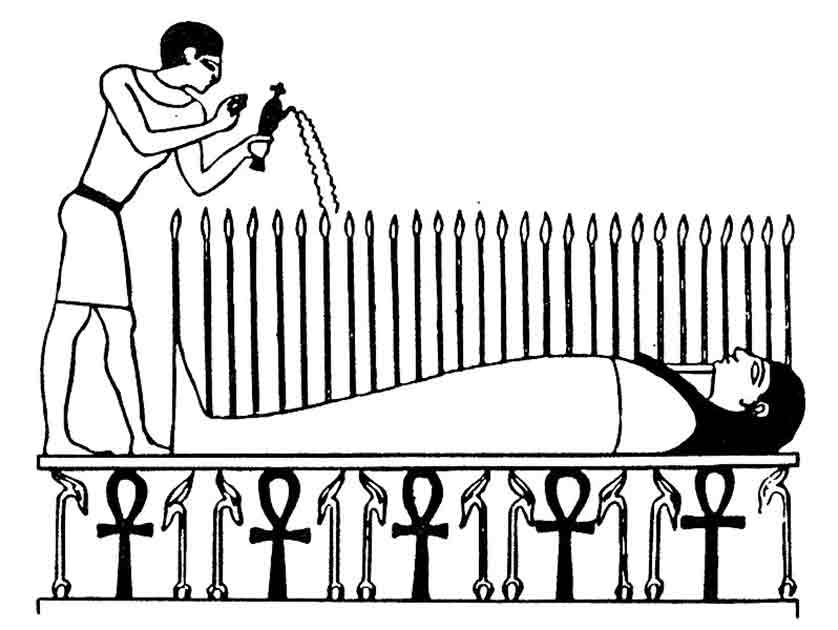

We can even see the variations based on the geography of the myth’s origin. Take the story of Isis and Osiris, for example. Osiris, murdered by his brother Set and dismembered, is resurrected by his wife Isis, becoming the lord of the underworld and judge of the dead.

This is a different myth because of what the ancient Egyptians saw around them: their world was not primarily dependent on seasonal changes in the weather, like the Greeks or other European cultures. Theirs was dependent on the Nile.

The Egyptians divided their land into two regions, the red and the black. The black region was the fertile area near to the banks of the Nile, named for the color of its soil. The red region was the unending desert that stretched beyond.

Set was lord of the desert regions, and his murder of his brother god represents the encroachment of the desert into the fertile banks of the Nile during the dry season. However the annual flooding of the Nile River, on which Egyptians depended on for agriculture, shows Osiris coming back to life and providing for his people. Isis is the agent of this rebirth for similarly straightforward reasons: bringing new life into the world was something only a woman can do.

Universal Construct or Cultural Variation?

The recurring motif of a dying and resurrected god across these diverse cultures suggests therefore a universal construct, rooted in the human experience of observing and interpreting the natural world. The death-rebirth cycle reflects a fundamental understanding of nature’s rhythms and the hope for renewal amidst decay and death.

This is a useful tool for understanding religion: as a way to explain the world around us using only our limited understanding of ourselves. However, it’s important to note that while this theme is prevalent in many ancient religions, it is not universal.

In other ancient traditions, such as those in Asia and the Americas, the conceptual framework can differ significantly. For example, in Hinduism, the concept of reincarnation and the cyclical nature of the universe (samsara) offer a different interpretation of life, death, and rebirth.

In the Americas, Native American mythologies often focus on the harmonious balance between nature and humanity rather than a death-rebirth cycle. They have their own stories, but these are based on different observations of the world to those of the ancient near east.

But for many religions, the myth of the dying and resurrected god serves as a profound metaphor for the cyclical nature of life. This motif repeats again and again across the ancient world and across time: Dionysus, Adonis, Marduk, Duzumi: they all fit this pattern. Interestingly, some religions also explore what happens when the dead god does not come back: Baldr does not come back in Norse mythology, and his death precipitates the doom of the gods.

It offers a recognition from these ancient cultures that they lived in their lands entirely dependent on the forces of nature they could neither fully explain, nor hope to control. They depended on the cycle of the seasons and the miracle of fertility for their existence, and they called these natural forces gods.

Top Image: Many religions across the ancient world had a resurrected god, and their presence and purpose tells us something fundamental about religion itself. Source: Txllxt TxllxT / CC BY-SA 4.0.

By HM Editorial Staff