Chinese pyromancy is the ancient art of divination through fire, or, in other words, seeing the future through burning things. It’s one of the earliest and most fascinating practices in ancient Chinese culture. The practice is predominantly linked with the use of oracle bones, and this specific type of divination played a key role in the political, social, and religious life of early Chinese civilizations. Those skilled in pyromancy were said to be able to read the cracks formed by flames in the remains of animals to read the future and give advice to leaders. Today, pyromancy is a lost art form, and artifacts from the pyromancers are incredibly rare and sought after. While many today might scoff at the idea of divination, the ancient Chinese took it very seriously indeed.

- The Tragic Love Of Yang Guifei and The Emperor Of China

- Song Emperor Taizu: Shadows By The Candle And Sounds From The Axe

What is Chinese Pyromancy? Origins and History

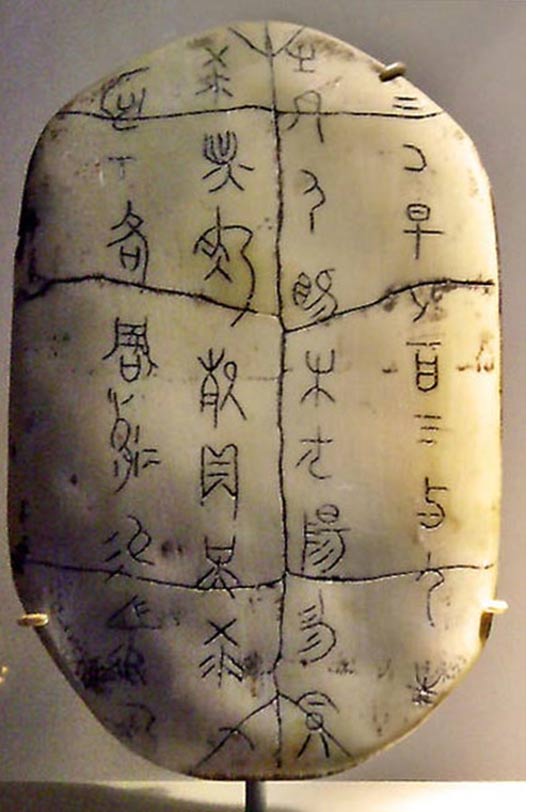

Chinese pyromancy, or “pyro-osteomancy” to give it its proper name, is just as fascinating as it sounds. It’s an ancient form of divination that is believed to date as far back as the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BC). The art revolves around the reading of patterns of cracks that form on animal bones and tortoise shells when subjected to intense heat.

Not just superstition, pyromancy played a significant role in the spiritual and administrative functions of the Shang rulers. In times of need, they often sought divine guidance on critical issues such as harvests, warfare, and royal succession.

Chinese Pyromancy stems from the early Chinese belief that both the natural and supernatural worlds are deeply entwined. The diviners, who were usually high-ranking priests or shamans, inscribed questions directly onto the bones or shells. These questions addressed a wide range of concerns, reflecting society’s reliance on divine intervention and approval. Once inscribed, the bones or shells were heated until they cracked. The resulting patterns were then interpreted as messages from the ancestors or gods.

- Hypogeum: The Oracle Room Of Ħal Saflieni

- Practical Magic: The Summoning Spells of The Book of Abramelin

While generally rare, thousands of oracle bones have been found at the site of Yin, the Shang Dynasty’s last capital. These have provided a wealth of information about this ancient practice. They’ve not only taught modern scholars how the practice was carried out, but also given us insights into the language, writing system, and even daily life of the Shang people.

Unfortunately, the practice fell out of use and was continued until at least the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BC). During this period, it gradually evolved, and, like most superstitions, became less respected. While still practiced, it was no longer central to important political decision-making (probably not a terrible thing). Pyromancy may have declined, but its influence persisted throughout Chinese culture and spirituality.

How Does It Work?

Chinese Pyromancy wasn’t as simple as jotting a question down on a bone and tossing it into the nearest fire. Like any religious ritual, it was a meticulous and ritualized process reserved only for those who knew what they were doing.

Divination began with the selection of a suitable bone or tortoise shell. The divination materials were chosen based on their durability and the clarity of cracks they produced when heated. The bones were typically oxen (although later people confused the artifacts for dragon bones), and the shells came from freshwater turtles, mainly female due to the shape of their shells. This being said, bones from sheep, boars, horses, and deer have also been found. Most are the scapulae, but some ribs have also been found.

The next step was to cleanse the bone and then carefully inscribe it with a series of questions. The bones were cleaned of meat and then sawed, scraped, smoothed, and polished until smooth. Pits or holes were then drilled into the bone or shell. The shape of these is the easiest way to date oracle bones, as the methods changed over time.

Next, the bone/shell was anointed with blood, and the inscription, called the preface, was prepared. On the bone, the date (recorded using the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches system) was recorded as well as the name of the diviner. The question itself was then added. These were usually directed at either ancient ancestors or deities and written in early Chinese characters. The questions themselves ranged from the mundane, like why the emperor had a toothache, to the outcomes of battles and whether the gods were pleased by certain rituals.

Next came the exciting part. An intense heat source, often a hot metal rod, was exposed to the pits and holes that had been drilled earlier. The heat caused the material to crack in distinctive patterns that diviners were trained to read. Typically, multiple cracks were read in one session, although how many is unknown.

Exactly how the diviners interpreted the cracks is unknown. It’s believed that the same bone could be used multiple times by changing the date inscribed on it, and most answers were simply a binary positive or negative result. The result of the divination would be recorded, and if the king was present, he would add his “prognostication,” his reading of the divination. On exceedingly rare occasions, these notes were added to the bone directly.

The Scarcity Of Oracle Bones

Today, genuine oracle bones are relatively scarce and hard to come by. This rarity is due to several factors.

For a start, Chinese pyromancy used organic materials. The problem with organic materials is that they’re prone to decay over time, especially if not well kept. Bones might be fairly durable, but they can still degrade when exposed to environmental elements such as moisture, soil acidity, and microbial activity. Furthermore, heating bones can make them brittle, making the survival of any oracle bone impressive.

Secondly, like any artifact, the survival of the oracle bones has been at the whim of mankind. Wars, especially during turbulent periods like the Warring States period (475-221 BC), and the resulting dynastic shifts often resulted in the deliberate destruction or looting of cultural and religious artifacts. Oftentimes, the sites containing oracle bones could have been destroyed, their contents scattered or repurposed for other uses.

Not all destruction was malicious. Over time, historical attitudes change, and new rulers try to distance themselves from the practices of their predecessors. Pyromancy is largely associated with the Shang Dynasty and from the Zhou Dynasty onwards, pyromancy fell out of practice. Old oracle bones had no perceived value, and it is likely most were simply discarded or overlooked.

These factors, combined, have resulted in the limited number of pyromancy artifacts available to historians and archaeologists today. Nonetheless, the oracle bones that have been discovered provide invaluable insights into early Chinese civilization, shedding light on their religious practices, social structure, and written language.

Conclusion

Chinese pyromancy is a fascinating relic of a bygone age. Every ancient civilization had its own esoteric practices, and pyromancy is one of the more interesting. It offers a fascinating glimpse into the spiritual and societal framework of early Chinese civilization. Through the interpretation of cracks on animal bones and tortoise shells, the Shang Dynasty and subsequent periods sought divine guidance on critical matters.

Despite the limited number of surviving artifacts, these oracle bones have provided a wealth of historical and cultural knowledge. The decline of pyromancy and the subsequent loss of many artifacts underscore the dynamic and evolving nature of cultural practices. Nevertheless, the legacy of Chinese pyromancy endures, reflecting humanity’s never-ending quest to understand the unknown.

Top image: A Shang dynasty oracle bone from the Shanghai Museum. Source: Shanghai Museum/CC BY-SA 3.0