Experimenting With Electricity

Andrew Crosse was a 19th-century man with enough monetary means to afford to spend time at his hobby of dabbling in scientific experimentation involving electricity. Actually, it was more of an obsession than a hobby.

He built a state-of-the-art laboratory at his English countryside house and read up on similar research going on around the world.

Did Andrew Crosse create a new life form?

Results Were Not What Andrew Crosse Expected

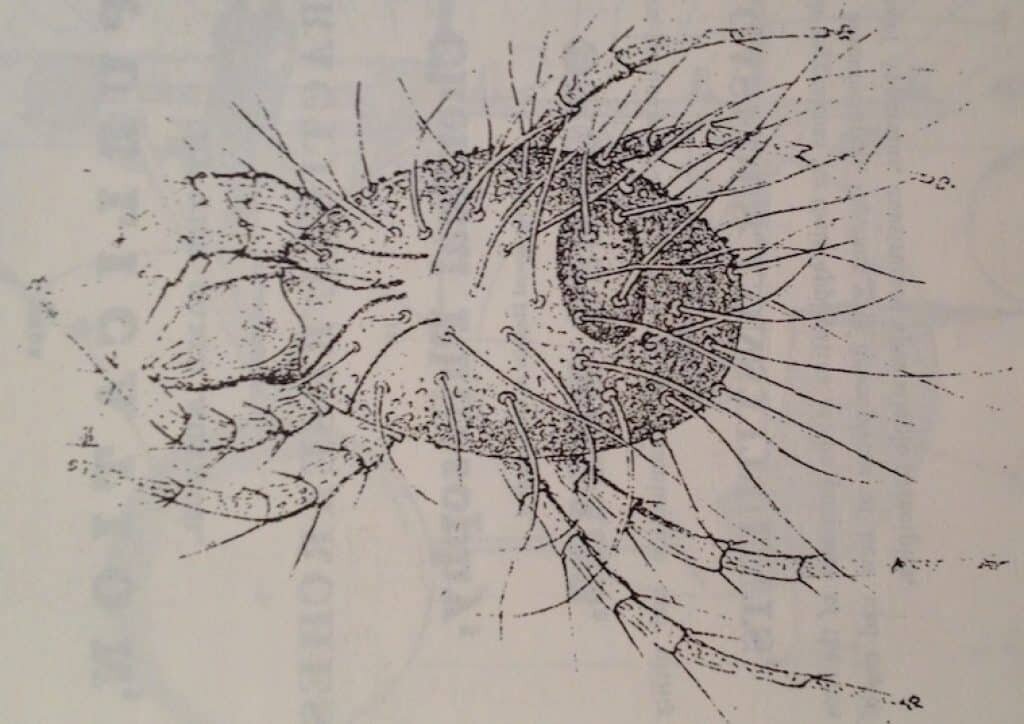

In 1837, he began an experiment to see if he could grow crystals via a weak electric current. He set up his experiment, which consisted of lava stone, a chemical mixture, and an electrical source, and prepared to wait. Days went by without results and Crosse was starting to become discouraged. However, 28 days after the experiment began, he noticed something unexpected. In the liquid of the experiment, instead of crystals, were numerous insects, all resembling some kind of mite or tiny flea.

He naturally presumed that the stone or liquid utilized in the experiment had been the home of microscopic insect eggs. The electrical stimulation must have caused the eggs to hatch. Oddly, though, no eggs had been seen originally, and no shells were to be seen after the insects appeared. Containers of the same chemical liquid source showed neither insects nor eggs.

Curious, Andrew Crosse replicated the experiment using sealed containers to prevent contamination from the outside. And he was rewarded with the same result: insects easily discernable in the experiment’s containers.

He attempted the same experiment using various poisonous liquids inhospitable to life. In most of these experiments, the tiny insects appeared.

Life appeared to be created out of a rock, some chemical liquids, and a weak electrical charge.

Wondering about the meaning of all this, he contacted the London Electrical Society, to see if they could make sense of these seemingly impossible experimental results.

A drawing of Acarus Crossii.

Backlash

Newspapers quickly caught on to the story, calling this new insect Acarus Crossii and inflamed the populace into a frenzy. They labeled Crosse a blasphemer, a devil, a mere man who dared to make himself equal to God by seemingly creating life out of nothing. People subsequently traveled to his neighborhood to mock his work, damage his property, or perform exorcisms outside his home.

He would later defend himself as being equally ignorant about his own experiments and what they meant:

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Andrew Crosse”]In fact, I assure you most sacredly that I have never dreamed of any theory sufficient to account for (the insects’) appearance. I confess that I was not a little surprised, and am so still, and quite as much as I was when the (insects) first made their appearance… I was looking for (crystal) formations, and (insects) appeared instead…[/blockquote]

Other scientists would replicate the experiment and come to the same result. However, they did not suffer the same harsh criticism Crosse received.

In addition to those outraged by the religious implications of Crosse’s experiments, other detractors stated that microscopic eggs must have been purposely deposited in the liquids and that Crosse was deliberately leading the public astray.

Crosse eventually became a virtual prisoner in his home. He was rarely able to appear in public without someone decrying him and his work. He died in 1855, still not knowing what, if anything, he had discovered — and still not understanding the world’s vicious reaction to his work.

Acarus Crossii Mystery Remains

The question remains: What, if anything, did Andrew Crosse discover? Apparently no modern scientists have seriously attempted to replicate his experiments. What exactly formed in the vials and vessels of a small English laboratory 175 years ago may never be known.

Sources:

“Crosse’s Acari,” The Journal of Borderland Research website, pulled 1/16/13

Wikipedia