In 1957, Homer H. Dubs, the author of A Roman City in China, made a controversial proposal about the lost Roman legion of Marcus Crassus. He believed that around 50 BCE, the soldiers ended up as prisoners of war. Eventually, they became mercenary soldiers for the Han Chinese who gave the Romans land in the Gansu province. There, the Romans founded a city called Lijien (also Liqian or Lijian), the word that the Chinese used for legion. Some of the people who live in Lijien — today, “Zhelaizhai” — have Caucasian features. Consequently, Dubs believed that the residents of Zhelaizhai may be the descendants of the lost Roman legion in China.

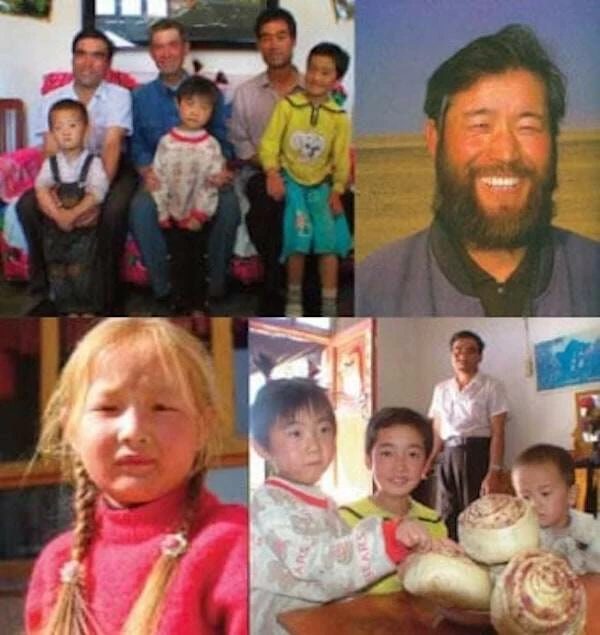

These Uyghur girls are genetically similar to a few residents of Liqian, today’s ZhelaiZhai. Public domain.

Marcus Crassus and His Legion of Roman Soldiers

In 53 BCE, a humiliating defeat for a Roman army set off a chain of events. Consequently, this may have led to the furthest eastward expansion of the Roman Empire’s military and cultural influence. The defeat took place at the Battle of Carrhae, located in eastern Turkey, where the Roman fought against 10,000 Parthian archers against seven Roman legions led by Marcus Licinius Crassus.

Prior to this battle, Crassus had amassed a degree of fame after he defeated Spartacus’ rebellion in 71 BCE. However, his success would not last. Despite his prior conquests, many people questioned his military leadership. The leader’s inexperience became apparent the day he led 45,000 soldiers into battle against the very prepared and mobile Parthian cavalry in Carrhae, now known today as Harran, Turkey.

By nightfall, the battle was all but over. The Parthians beheaded Crassus’ son and killed 20,000 Roman soldiers. While the two sides were negotiating an end to the fight, the Parthians captured Crassus and also beheaded him. Approximately 15,000 Roman soldiers managed to escape, but 10,000 others became prisoners.

What Happened to the Lost Roman Legion?

The fate of the 10,000 captured Legionnaires remained a mystery. They became known as the Lost Roman Legion. In 20 BCE, under Caesar Augustus, negotiations regarding the return of these soldiers only compounded the mystery.

Roman Concrete: How Volcanic Material Created an Empire

The Parthians stated there were no prisoners to repatriate. However, Paul Brummell, the author of Turkmenistan, says that the Parthians moved many prisoners from the Battle of Carrhae eastward to Merv, Turkmenistan, where they used the fighters against invasions.

Lijian — Legion?

Chinese records indicate that in 36 BCE at the Battle of Zhizhi, the Han captured the Xiongnu, led by Zhizhi Changyu in Central Asia, in a place known today as Dzhambul, Uzbekistan, in 36 BCE.

Chen Tang, one of the Han generals who fought the Xiongnu, recorded fighting soldiers who used the yu lin zhen, fish scale, formation. This tactic of tightly squared units utilized shields for the first row to cover their body. The following rows covered their heads. However, the Roman legions used this strategy throughout the empire and called it the testudo (tortoise shell).

Roman Testudo tortoise shell formation. CC 2.0 Neil Carey.

Charles Hucker proposed that the Roman legionaries may have been amongst the Xiongnu soldiers. Following the Battle of Zhizhi, the Han possibly captured over a thousand prisoners. Emperor Yuandi established a new county called Lijian (Liqian) or Li-jien, which, according to Hucker, is a name that reflects the Roman legion.

The Theory of Liqian

As the story goes, the Han victors were highly impressed by the skills of the soldiers. Therefore, they moved them further east to the new outpost of Liqian (Li-Chien) in the Gansu province. From there, the mercenary soldiers helped the Han Chinese defend against Tibetan raids.

A map of China’s Han Empire available during this same period showed a county named Liqian. According to Fan Ye’s 5th century “Hou Han Shu”, Liqian was what the Chinese called the Roman Empire.

Zhelaizhai residents with European characteristics.

Archaeological Findings

Archaeologists now believe Liqian became present-day Zhelaizhai, China. Excavations in Zhelaizhai unearthed a trunk with stakes, which the Romans commonly used to build fortifications. Additionally, they found Roman coins and pottery.

Evidence shows that the people of Zhelaizhai had lined the ancient streets with tree trunks. This was a uniquely Roman practice. Also, at least one Roman helmet with Chinese lettering puzzled researchers, and a strange passion exists for bulls. However, neighboring cities do not.

Arguments Against the Lost Roman Legion in Liqian Theory

- The fish-scale formation was known to China, which had been using the strategy during the first millennium BCE. (Yuan: 2018).

- Indo-Europeans had spread out into Central Asia well before the Imperial Roman period. The Tarim mummies of Xinjiang, China, are just one example of this.

- Celtic mercenary soldiers fought in Central Asia and Asia in Turkey, Judea, Syria, and against the Seleucid Empire pre-imperial Rome. (Listverse).

DNA Tests in Zhelaizhai

A 2005 DNA analysis of residents in Zhelaizhai indicates that approximately 56 percent have genetic sequences similar to Europeans. However, the analysis did not determine that they derived from Southern Europe, as experts would expect if they originated in Italy. On the contrary, their DNA was similar to that of the Uygurs of the Xinjiang Province of Western China, who possess Northern European ancestry (Khan).

Another study from 2007 determined that according to paternal (Y) lineage DNA, the people of Zhelaizhai are not descendants of Romans. Instead, they are very similar, genetically, to Han Chinese with a small amount of Mongolian aspect. Scientists indicated that a complete study of mtDNA (maternal lineage) is necessary to complete the assessment.

Although the locals of Zhelaizhai have, in their minds, accepted the idea that they originate from the lost Roman legion in China, it appears that the evidence so far indicates that they do not.

Continue reading:

Underworld Reapers of Chinese Mythology

How Were the Terracotta Soldiers Made?

Italy’s Quest for the Ark of the Covenant

References:

Brummell, Paul. Turkmenistan: the Bradt Travel Guide. Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides, 2005.

“The Western Regions According to the Hou Hanshu.” The Han Histories. Accessed March 14, 2020.

Khan, Razib. “No Romans Needed to Explain Chinese Blondes.” Discover Magazine. Discover Magazine, October 21, 2019.

Zhou, Ruixia, Lizhe An, Xunling Wang, Wei Shao, Gonghua Lin, Weiping Yu, Lin Yi, Shijian Xu, Jiujin Xu, and Xiaodong Xie. “Testing the Hypothesis of an Ancient Roman Soldier Origin of the Liqian People in Northwest China: a Y-Chromosome Perspective.” Journal of human genetics. U.S. National Library of Medicine, February 2007.

*Article updated April 17, 2020