In the realm of archaeology, few discoveries ignite as much intrigue and debate as those challenging established narratives. Such is the case with the Cerutti Mastodon site, a Californian archaeological marvel that has sparked more than its fair share of controversy.

Nestled deep within its layers lie fragments of a mastodon skeleton, entwined with mysterious markings which some say are suggestive of human involvement. These supposed traces of ancient human activity, purportedly dating back a staggering 130,000 years, have left the scientific community divided.

As experts grapple with the implications of this extraordinary find, the Cerutti Mastodon discovery prompts us to reconsider our understanding of early human migration in the Americas. What happened to these animals, tens of thousands of years ago?

The Discovery

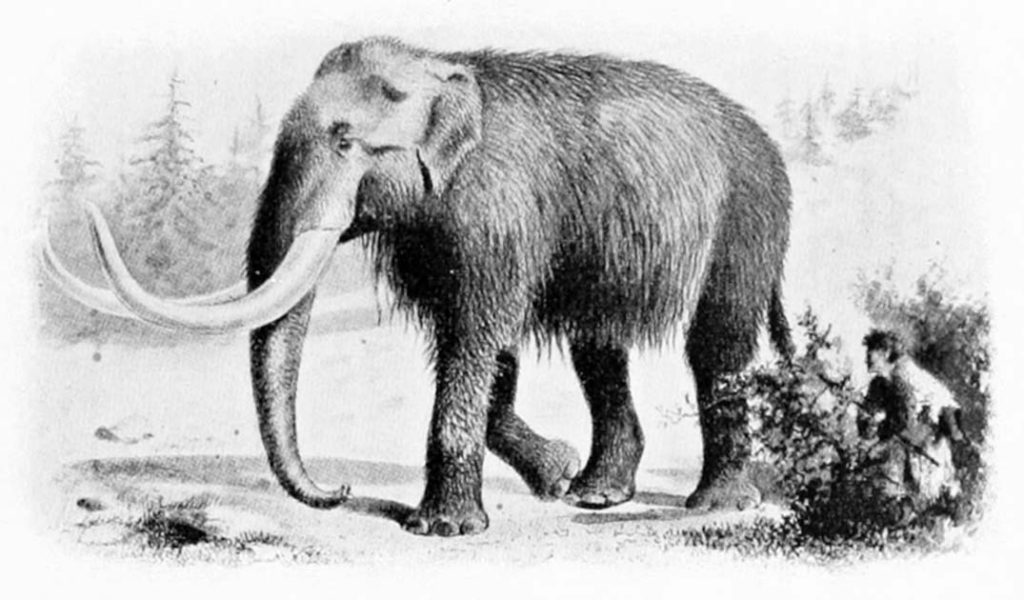

The most important find at the Cerutti site was the fossil remains of a young male Mammut Americanum, a type of Mastodon. Mastodons looked similar to elephants or mammoths but had longer, wider bodies and weren’t as tall, having stubbier legs. They also had more heavily muscled limbs with thicker bones: think elephants mixed with rhinos.

At the site, they found 2 mastodon tusks, 3 teeth, 4 vertebrae, 16 ribs, and over 300 bone fragments. Alongside the Mastodon’s remains they also found those of dire wolves, horses, camels, a mammoth, and ground sloth.

On their own none of these bones would be especially exciting. While finding a complete Mastodon skeleton is relatively rare, incomplete skeletons like the one found here are more common. Uranium-thorium dating of the bones revealed that the bones were around 130,700 years old, which also sounded about right. So why was this site so controversial?

Well, alongside the bones were five stones that showed signs of use by early humans. The research team who discovered the bones claimed that the stones had been used as hammerstones and anvils.

The team also took a closer look at the mastodon bones and said they found signs that the bones had been broken by early hominids (our ancestors). This is a problem, because we didn’t think there were any humans in America until much, much later: this would imply that some form of early Homo was in America over 100,000 years earlier than previously thought.

In particular, the original research team pointed out that many of the bones featured spiral fractures, which suggested the bones were still fresh when broken, and that there was evidence of percussion (that the bones had been banged against the rocks). They also claimed that due to how the bones were distributed, they were broken at the site.

All this points to the bone having been broken by early humans who were dexterous and knew how to use simple stone tools to extract nutritious bone marrow from the bones. Or perhaps how to use the bones to make more tools.

Knowing that other paleontologists would be dubious, the team compared the marks on the stones to those of confirmed hammerstones and anvils that had been used in bone-breaking experiments. They felt that their results confirmed the hypothesis that the stones had been used as tools.

A research paper released in 2020 backed up many of these claims. This team found microscopic pieces of bone residues on the upward facing surface of the rocks, with none on the other sides, implying they had been used to break the bones. If it had been the result of natural contact with the bones, the residue would have been found on all sides.

It has also been pointed out that the entire site was covered in siltstone, a sedimentary rock made up of fine-grained sediments. This type of rock is only deposited by slow-moving, low-energy water.

Yet the stones found at the site were far heavier than the surrounding particles, with one weighing over 30 pounds (13.6kg), too heavy for slow-moving water to have moved. If water didn’t move the stones, maybe humans did.

Larger animals trampling and breaking the mastodon bones was also deemed unlikely. Many of the mastodon’s more fragile bones, like the ribs and vertebrae, were found intact. These are exactly the type of bones that trampling would break first. Likewise, smaller animals like scavenging carnivores lacked the power to break through a large mastodon leg bone.

The Problem

So, case closed then? Were we wrong about when humans first migrated to America, and does this provide proof that they were in fact there for far longer than we thought?

The biggest issue with both teams’ claims is how outlandish they are. It used to be believed that early humans first inhabited the Americas around 13,000 years ago. This was later pushed back to between 15,000 to 24,000 years ago. Some fringe theories have proposed dates as early as 40,000 years ago.

But no one has ever got close to claiming anything like 130,000 years ago. If you’re going to try and rewrite the history books by over 100,000 years, you need hard, unequivocal evidence.

One of the main arguments against the team’s findings is that they don’t definitively rule out natural causes for why the stones are there, the marks, or the breakage of the bones. It’s unlikely that slow-moving water could have dumped the bones, but it isn’t impossible. Likewise, it’s not impossible that the marks on the stones were caused by them bumping together.

There are other problems too. Archaeologists are unhappy with what hasn’t been found at or near the site. Sites where hammer and anvil tools are found usually feature lithics. These are flaked stone tools and the debris that come from their manufacture. There’s no sign of either at the Cerutti site.

Experts also weren’t happy with the idea that the bones had been smashed for the purpose of making tools. If that was true, then why were the bones still at the site at all? As one researcher put it, “Everything that’s broken was still there, so it wasn’t mined for tools, and you’re certainly not getting marrow out of the bone of a mastodon tooth,”

The argument is still ongoing, and a definitive answer probably isn’t coming any time soon. For every argument one side makes, the other has a rebuttal.

The key problem is hard evidence is lacking on both sides. Many of the arguments for the stones being tools don’t prove it impossible that they weren’t created by natural processes. Likewise, the critics’ arguments that the stones and broken bones were the result of natural processes can’t prove definitively that they weren’t done by humans.

Interestingly, as time goes on it’s becoming increasingly likely that the original team was correct. If the site is 140,000 years old, then it’s possible that early humans crossed from Beringia while sea levels were still low.

Many experts agree that if the stones do prove to be tools, then the only possible answer is that early humans made them. There were no other stone-wielding mammals (like chimps or apes) in the Americas during this time who either ate bone marrow or were strong enough to wield 30-pound stones. The challenge, however, is going to be proving once and for all that the stones were man-made.

Top Image: Were the Cerutti Mastadons killed and butchered by early man, providing proof they were in America 100,000 years than earlier thought? Source: Charles R. Knight / Public Domain.