Beneath the waves of the North Sea lies a long-forgotten kingdom. Known as Doggerland, it is a submerged land that once connected what is now Great Britain to mainland Europe.

This Mesolithic landscape lost to the depths of time, offers a unique window into a prehistoric world. Hidden under the waves is a rich history that predates the separation of the British Isles from the European mainland, revealing a civilization that thrived in an era long before recorded history.

In recent years excitement around Doggerland has peaked and as the discoveries pile up its history feels more relevant to a situation today than ever before.

Britain’s Mesolithic Atlantis

During the Mesolithic period, around 10,000 to 6,000 years ago Doggerland was a sprawling expanse that linked modern-day Great Britain to mainland Europe. This submerged kingdom extended across what is now the North Sea and was a biodiverse lowland believed to have been inhabited by a Mesolithic population.

It was made up of river valleys, estuaries, and lush, rolling landscapes. And from what we can tell it was a veritable Garden of Eden.

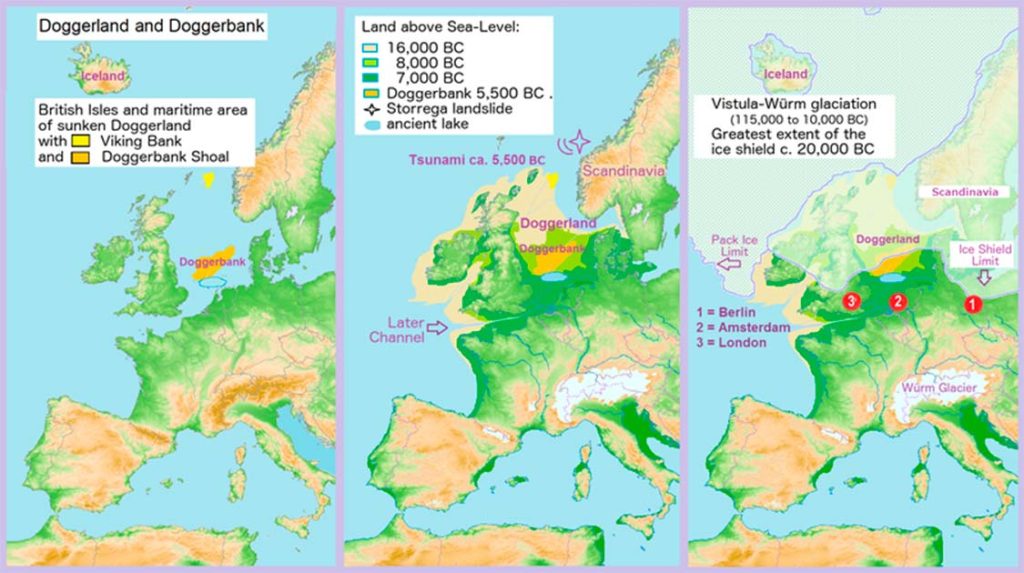

Situated in what is now the North Sea basin, Doggerland was a land bridge created by lower sea levels resulting from the last Ice Age. The presence of ancient river valleys beneath the sea attests to the region’s once-vibrant ecosystems and the likely presence of human settlements.

It is this human presence that is so exciting. It’s believed Doggerland was home to nomadic hunter-gatherers who migrated as the seasons changed, fishing, hunting, and foraging Doggerland’s lush landscape for goods like nuts and berries.

- Tyno Helig: Have we found the Welsh Atlantis?

- Kumari Kandam: Is There a Lost Continent South of India?

While Doggerland may be deep beneath the waves today, it is a treasure trove of Mesolithic artifacts. This lost world may have much to teach us much about Britain’s earliest settlers and their swap from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to an agricultural one.

So how does such a huge landmass disappear, never to be seen again? Well, perhaps a warning of things to come, we have global warming to thank for Doggerland’s disappearance.

As temperatures warmed up and ice melted at the end of the last glacial period vast amounts of water were released, causing a rise in sea levels. At the same time, the land itself began to tilt as the massive weight of all that ice relaxed in what is called an isostatic adjustment. Almost like a teeter-totter as the once ice-laden land rose, Doggerland sank even further into the rising sea levels.

By around 6500 BC Doggerland had sunk to the point that the British peninsula was completely cut off from the European mainland, and Britain became an island. All that was left of Doggerland was an upland area called Dogger Bank which remained an island until roughly 5000 BC.

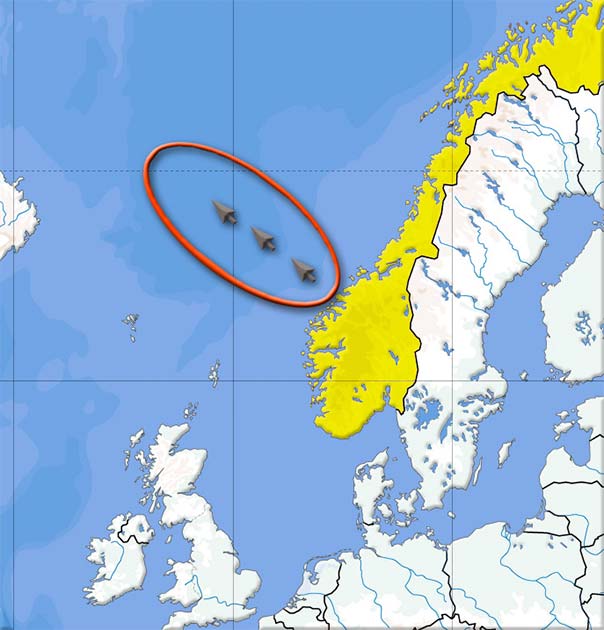

More recently it has also been hypothesized that a massive tsunami hit Doggerland around 6200 BC, flooding its coastal areas. Believed to have been caused by a submarine landslide off of Norway’s coast known as the Storegga Slide, this tsunami would have been devastating, basically putting an end to its Mesolithic population. At least one-quarter of the people of Britain would likely have been wiped out and what was left of Doggerland quickly abandoned.

An alternative theory downplays the devastation caused by the Storegga tsunami. According to this theory, after the tsunami sea levels briefly returned to normal. It was only later when the North American Lake Agassiz burst, releasing unimaginable amounts of fresh water, that sea levels rose, flooding Doggerland.

Evidence of Doggerland

It can be hard to wrap one’s head around the idea that not only Doggerland existed but that it held a large Mesolithic population. After all, history is full of legends regarding mystical lost lands and their civilizations. Could Britain really have had its own Atlantis?

Thankfully, there is plenty of evidence to back up these claims and we’ve had evidence of Doggerland since the late 19th century. By 1913 the famous British geologist and paleobotanist Clement Reid was studying plants that had been dredged up from the seafloor.

Other paleontologists of the time were studying animal remains and working flints from as early as the Neolithic period that had been found by fishermen. Sir Arthur Keith’s 1915 book The Antiquity of Man laid out how important the region was going to be to archaeologists going forward.

The first big breakthrough in Doggerland research came in 1931 when the trawler Colinda accidentally hauled up a large lump of peat near Ower Bank 40km (25 miles) off the Norfolk coast. The peat was found to contain an ornate barbed antler point believed to have been used as a harpoon 10,000 to 40,000 years ago.

Over the decades more finds were dredged up and modern fishermen have repeatedly found ancient bones and flint tools in their nets that have been dated to around 9000 years ago. This led to a slow build-up in interest in the area until the 1990s when prehistoric archaeologist Bryony Coles released the first speculative maps of the area she dubbed “Doggerland”. Based on the current relief of the North Sea seabed she admitted these maps were likely inaccurate, but her research inspired more and more British and Dutch archaeologists to join the cause.

From 2003 and 2007 researchers from the University of Birmingham used seismic data volunteered by big oil companies to create a digital model of nearly 46,620 square kilometers (18,000 square miles) of Doggerland. Even more excitingly, the 2000s have seen extensive discoveries of textile fragments, paddles, more flint tools, and even Mesolithic dwellings.

Away from the British coast near the Netherlands, Neolithic settlements with sunken floors, dugout canoes, fish traps, and even burials have been found. Divers have even found evidence of prehistoric forests in the area via the discovery of compressed trees and branches.

Today the story of Doggerland is told through archaeological findings and seismography. It’s amazing to think that until modern times its entire existence was completely forgotten, with little evidence of Doggerland affecting local folklore or legends. It’s almost the converse of Atlantis we’ve speculated for generations about the location of Atlantis but found nothing while Britain had a literal Atlantis on its doorstep, we knew nothing about.

For those interested in Doggerland these are exciting times, interest is at its peak and the discoveries keep mounting up. But some of these discoveries are more than a little worrying.

Researchers are finding that the climate change that drowned Doggerland is analogous to what we face today. Just as the glaciers melting rose sea levels it’s estimated the ice caps melting today could affect the lives of billions of people who live in low-lying lands. Today all that’s left of Doggerland’s once thriving population is relics and bones, a fate we would do well to try and avoid.

Top Image: Skull of a mammoth from Doggerland, found in the North Sea off the Hook of Holland. Source: Ogmios / CC BY-SA 3.0.