Lost treasures loom large in pop archaeology. Aside from the obvious material gain of figuring out in which cave the Inca hid their gold, or which buried sandstone slab conceals the lost tomb of a pharaoh, such hordes are uniquely valuable for what they can tell us about those who hid them.

And the Vikings, of course, buried treasure as much as any thief. With a name that literally means “raider”, these early pirates and their berserker warriors stole much, and much of what they stole remains unrecovered.

Much of what we know about the Vikings comes primarily from Icelandic poetic sagas about the gods, kings, warriors, and conquests written hundreds of years after the events occurred. Like any saga, the information in the works may be rooted in past events, but some details are exaggerated because sagas were recited as entertainment.

One of the most entertaining and unique Vikings was a man named Egil Skallagrímsson, a poet, warrior, and the source of a hidden treasure still waiting to be found in Iceland. We know much from the mythology, but who was the real man?

And where is his horde of silver?

Egil Skallagrímsson

According to the sagas, Egil Skallagrímsson was a lot of things. A war poet, a feared warrior and berserker, and a farmer, he is believed to have been born around c. 904 and died a very old man around 995 AD.

Most of what we know about Egil Skallagrímsson comes from a Norse Saga known as Egil’s Saga, in which Egil Skallagrímsson is depicted as an anti-hero. Egil was one of two sons of the respected chieftain, Skalla-Grímr, who was the enemy of King Harald Fairhair of Norway; Skalla plays a significant role in Egil’s Saga.

Egil Skallagrímsson showed his talent for poetry and his spitfire personality at the tender age of three. Chapter 31 of Egil’s Saga tells the humorous tale of young Egil Skallagrímsson being told by his father that he could not attend a feast his grandfather Yngvar was hosting.

Apparently, Egil was a rowdy child, and Skalla didn’t want to deal with a drunk and misbehaving son. It seems that the child was a lightweight when it came to booze, which is to be expected of a three-year-old. Not wanting to miss out on some fun, Egil Skallagrímsson “found” a horse and rode it to the feast, where he gave his first poetic performance. According to Egil’s Saga, the child said:

“Here I am at the hearth

Of my host, Yngvar

The Generous, who grants

Gold to heroic men;

Free-handed fosterer,

You’ll find no three-year

Babe among Bards

More brilliant than me.”

Indeed, historians and poets now consider the real Egil Skallagrímsson to be one of the best composers of Old Norse poetry. The kind of poems Egil wrote were known as Skaldic poems, which were incredibly complex compared to the more common Eddic poetry.

There is heavy use of kennings, complex formal nouns, and the most common form of skaldic verse he composed was dróttkvætt meter, which uses an internal rhyming scheme and lots of alliteration. Egil wrote a dirge when his son died, and this 25-stanza-long poem is said to have been the “birth of Nordic personal lyric poetry” and the first Old Norse poetic verses to utilize end rhymes.

You Won’t Like Egil When He Is Mad

While he became known as a great poet, Egil was also a brutal Viking. When he was either six or seven years old, Egil Skallagrímsson was playing with some local boys when one boy cheated him.

Egil became enraged and exhibited the first sign of his future as a berserker by going home, grabbing an axe, and returning to the group of boys to seek revenge. Egil took the axe and “split the skull [of the boy who cheated] to the teeth.” Berserkers were individuals who would fall into a trance-like state of rage when engaging in battle, and Egil certainly seemed to have this quality.

As he grew older, Egil Skallagrímsson maintained his fighting spirit, and when his father-in-law would not let Egil claim his wife’s share of her inheritance, he challenged his father-in-law to a hólmanga. A hólmanga was a man-to-man fight on an island that was considered a legal way to settle disputes in medieval Scandinavia.

A hólmanga was to be fought 3-7 days following a challenge, and should one of the parties not arrive for the duel, they are the losing party and deemed an outlaw. If both parties showed up for the duel, it went like most standard duels do: the person who lives is the winner.

In this instance, Egil Skallagrímsson’s father-in-law refused to fight Egil. Not long after the challenge was issued, Egil killed him and his brother Hadd, as well as another brother, Atli the Short, by biting through his neck during a hólmangar.

Egil’s Saga further tells of what the crazy poet would do when he was mad or had been insulted. For example, after killing a retainer of King Eirík Bloodaxe, who was the King of Norway from 932-934 AD, his wife, Queen Gunnhildr, ordered her brother to kill Egil and his brother. Before the Queen’s brothers could kill the Skallagrímsson brothers, Egil killed them first.

The animosity between King Eirík Bloodaxe and Egil Skallagrímsson escalates further, and chapter 57 of Egil’s Saga describes Egil placing a curse on the King and Queen using a pole with ruins carved into the wood with the head of a dead horse on top. The curse was for the King and Queen to be ousted from Norway.

The curse worked because King Eirík Bloodaxe and Gunnhidlr were forced to flee to the Kingdom of Northumbria, where they became the new King and Queen of that kingdom. The beef between the two men continued, and after becoming shipwrecked in Northumbria and discovering who the king and queen were, Egil and a friend took up arms and marched to King Eirík’s court.

Egil’s friend told him he “must go an offer the king your head and embrace his foot. I will present your case to him.” Egil did just that and composed a short skaldic poem he recited to King Eirík.

The King was not impressed by the prose and ordered Egil to be executed immediately. Luckily, Egil’s friend convinced King Eirík to wait until morning before killing Egil.

Egil’s friend told him to stay up all night and “compose a mighty head-ransom poem” (known as a drapa) for the king, telling him how fabulous and wonderful of a king he was. Egil wrote a twenty-stanza-long drapa, which can be read in Chapter 36 of Egil’s Saga, and the poem was so good and complex that King Eirík decided to spare Egil’s life.

Egil’s Silver

In 937 AD, Egil Skallagrímsson and his brother fought for Æthelstan, King of England, during the Battle of Bruanburh. Egil’s brother was slain in battle, and Egil was rewarded two chests full of silver from Æthelstan as compensation for the loss.

Now aging, Egil returned to his family’s farm in Iceland, where he became involved in local politics for a few years. Before his death, Egil took two servants and his silver deep into the hills of Mosfell, about 20km (12.5 miles) to the east of Reykjavik, and there he buried his hoard of silver… somewhere.

To ensure nobody would steal his silver, and for one last moment of bloodshed, he then killed the two servants who had helped the old man hide the silver. What happened to the silver remains a mystery to this day, and many modern treasure hunters have embarked on the quest for Egil Skallagrímsson’s long-lost silver.

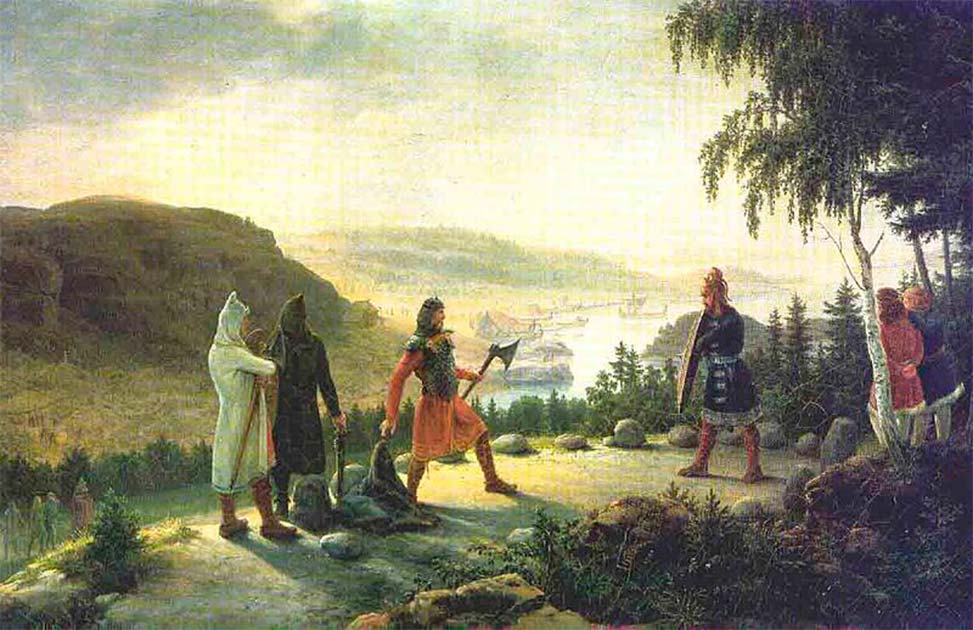

Top Image: Egil Skallagrímsson hid his treasure somewhere in the hills near Reykjavik. Source: AdamantiumStock / Adobe Stock.