Nobody knows exactly when the ancient society we now call the Etruscans inhabited parts of modern-day Italy, but we do know that they were a thriving culture until the Romans defeated them in the 400s BCE.

While artifacts from the Etruscans are relatively easy to find, archeologically speaking, the language is an ongoing puzzle for linguists, and nowhere is that riddle more apparent than in a rough cloth document known as the “Linen Book of Zagreb.”

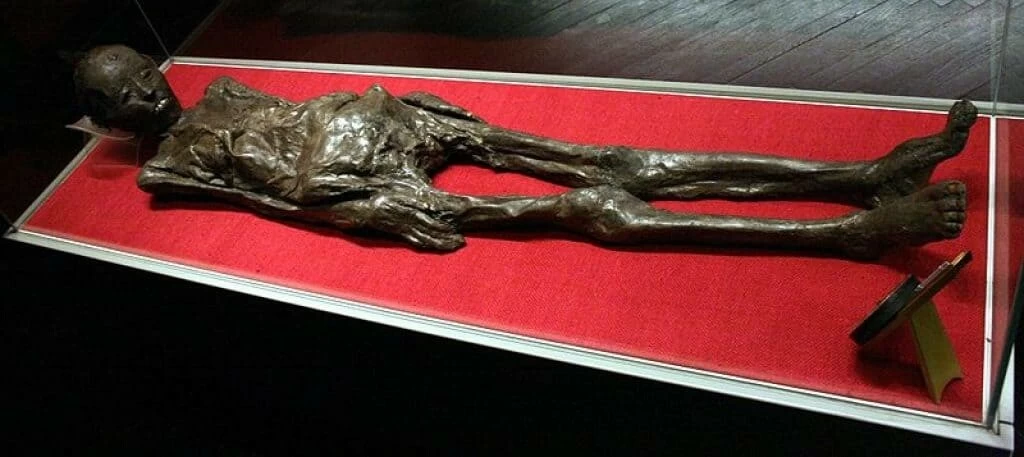

The female mummy has been identified as Nesi-hensu. Image: SpeedyGonsales

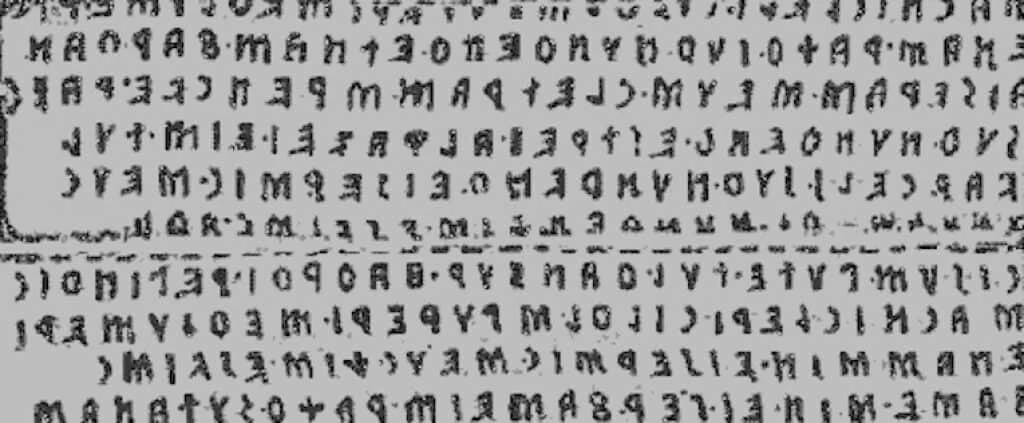

We do have some limited knowledge of Etruscan writing, so we can make fairly confident guesses about its purpose, and it seems like it might have been used as some kind of religious calendar indicating when holidays honoring the gods were to be held. It might even describe religious rituals themselves. The Etruscans had a pantheon of gods including Aita (god of the underworld), Aminth (a god of love), Malavisch (deity of mirrors), Nortia (goddess of fate), Rath (possibly a sun god), and Sethlans (the god of blacksmiths and craftsmen). Etruscan gods and goddesses may have been original to that society or they may be gods of the Romans under different names.

The Linen Book was written in the mid-200s BCE and the fact that we cannot tell its original location is an odd twist to the enigma.

It all goes back to a Croatian man named Mihajlo Barić who visited Alexandria, Egypt in 1848 and came across a sarcophagus for sale on the streets of that city. He brought it home to Vienna where it graced his house as a somewhat grim decoration. To make the showpiece even grimmer, he eventually peeled the wrappings off the mummy and displayed them separately, apparently not noticing that there was what appeared to be writing on the linen.

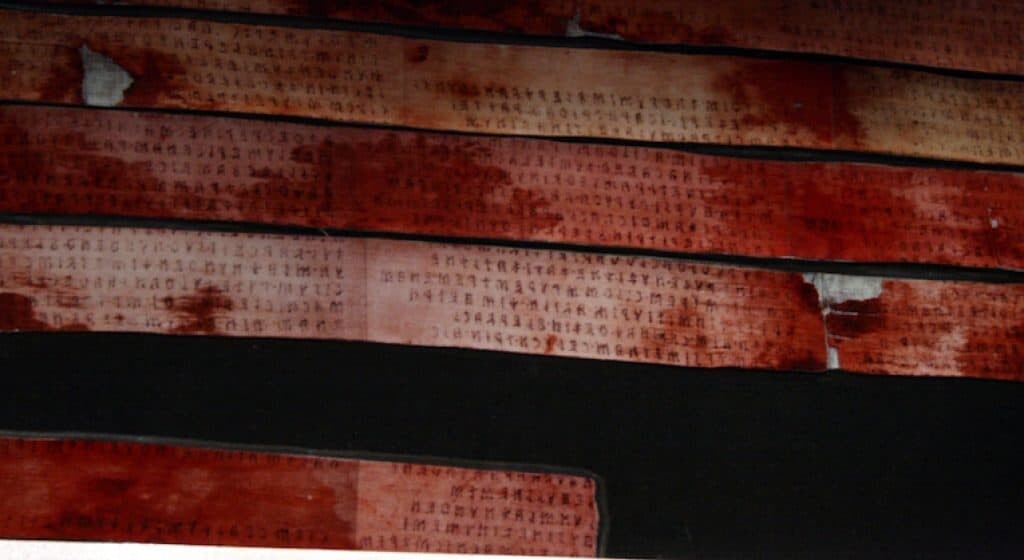

The text is clearly visible on the linen. Image: SpeedyGonsales

After his death, the mummy and wrappings found their way to the present-day Archaeological Museum in the city of Zagreb, the capital of Croatia. At the time it was described at the museum as:

Mummy of a woman (with wrappings removed) standing in a glass case and (also another) glass box containing the mummy’s wrappings which are completely covered with writing in an unknown language….

So the museum noticed the writing that Mihajlo seems not to have seen.

Researchers set to work to try to decipher the strange characters on the bandages. Scholars of ancient hieroglyphics and scholars in the Coptic language examined the writings and determined they were neither of those Egyptian languages. Finally, a researcher named Jacob Krall assembled the linen sheets into a single piece and was able to determine that the language was, in fact, of the ancient Etruscans.

So what was a piece of cloth written with a language by a people of ancient Italy doing wrapped around an Egyptian mummy? And what did the writings say?

One clue is that a papyrus found along with the mummy stated, in understandable hieroglyphics, that the mummy was a woman named Nesi-hensu, who was the wife of a tailor named Paher-hensu. But that still doesn’t answer the mystery of the linen’s trail from Italy to Egypt and the meaning of the writing.

The mysterious texts found on the linen are believed to be of Etruscan origin.

Linguists will continue to pore over the Linen Book of Zagreb, because, once its code is cracked, it will represent the largest known single record of the ancient Etruscan language. Perhaps until an equivalent to the Rosetta Stone is found for that language, it will continue to be deciphered one word at a time by linguistic scholars and cryptologists.

Sources

“Liber Linteus”, Wikipedia, pulled 6-10-16.

“10 Ancient Archaeological Mysteries That We May Never Solve”, Listverse, pulled 6-10-16.

“The Liber Linteus: An Egyptian Mummy Wrapped in a Mysterious Message”, Ancient Origins website, pulled 6-10-16.