These days we live in a world of cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and contactless payment, leaving many people fearing that physical currency will soon be a thing of the past. The coins in our pockets might feel old-fashioned to some, but they were once revolutionary.

The ancient Lydians stand as pioneers in the realm of economics, leaving an indelible mark with their groundbreaking invention: coinage. The evolution of trade and societal needs converged in Lydia, sparking an innovation that would reshape economies across the ancient world.

The Lydians are widely regarded as creating history’s first coins. Who were the people behind this revolutionary concept, and what was it about their invention that was so new, and so important?

Meet the Lydians

The Lydians were a society that inhabited the ancient region of Lydia (the western part of present-day Turkey). Believed to have been founded around 1200 BC, the Lydian Empire really began to flourish during the 7th century BC and for a while there they were the Anatolian civilization.

The Lydian Empire was in a prime strategic position, its lands were rich in natural resources, and they were strategically located for trade, meaning they quickly cultivated a thriving economy. Their capital, Sardis, was one of the region’s most prominent centers of both commerce and culture.

The Lydians became renowned for their craftsmanship, especially when it came to metallurgy and jewelry. As the civilization’s wealth increased it also became increasingly clear they needed a way to regulate their economy. The answer lay in their advanced metallurgy.

Unfortunately, while their affinity for wealth accumulation laid the foundation for the groundbreaking development of coinage, it would also ultimately plant the seeds for their destruction. They got so good at being rich that in the sixth century BC their wealth and countless advancements attracted the attention of the powerful Achaemenid Persian Empire led by Cyrus the Great and all the coins in the world couldn’t save them.

- Operation Bernhard: Nazi Economic Blitzkrieg and a ton of Fake Money

- Hattusa: The Great Hittite City At The Edge Of The World

So what about this great invention? The first coins started to appear during the 7th century BC. While historical records may not pinpoint a single individual responsible for the “invention” of Lydia’s coins, the Lydian King Alyattes and his successor, Croesus, are most often associated with this fiscal innovation.

It was during their rules that the Lydians first collectively embraced the concept of a standardized currency. This marked departure from earlier barter systems was a response to the growing complexities of trade and commerce. The Lydians recognized the need for a more practical and universally accepted medium of exchange, a go-between which solved all their major trade problems at a stroke.

The transition from cumbersome barter, where goods were directly traded for other goods, to a system of standardized coins represented a leap forward in economic evolution. This innovative breakthrough not only streamlined transactions but also laid the groundwork for a more sophisticated and interconnected commercial world.

It also made the Lydians, and their kings, extremely wealthy. They could, and would, buy anything from anyone, and that meant they also possessed just about anything a passing trader could want. Trade became extremely straightforward, and Croesus, especially, became very rich.

This being said, the idea that the Lydians created the first coins isn’t without some controversy. Some historians claim that ancient China, dating back to the Western Zhou period (1046–771 BC) had the first coins.

This period saw the invention of “spade” and “knife” money that resembled agricultural tools. Made from bronze, over time the design and shapes of Chinese coins evolved, including round coins with a square hole in the center, a characteristic feature that persisted for centuries.

However, it wasn’t until the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) that Chinese coinage became standardized, and round coins with square holes were used through various dynasties, including the Han, Tang, Song, and Ming. Arguably, this late standardization puts the Lydian coins back in first place.

Why Adopt a Standardized Coinage?

So why did the Lydians move away from the trade and barter system that humans had been using for thousands of years? Well, the bigger the Lydian economy became, the more the barter system, reliant on the direct exchange of goods, proved increasingly impractical. The inherent challenges of bartering, such as the lack of a standardized unit of value and the complexity of negotiations, created a pressing need for a more efficient medium of exchange.

Lydia was a hub for trade and commerce. The Lydians traded extensively with neighbors like the Ionian Greeks, Phrygians, and Persians. The use of standardized coins would have facilitated trade by providing a widely accepted and easily transportable medium of exchange. It’s much easier to transport bags of coins than raw materials.

Lydia was full of natural resources, including rich deposits of electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver. Pretty ideal for making a coinage, these deposits of electrum may have inspired the Lydians to develop a standardized system of coinage, making it more convenient to measure and exchange this valuable resource.

The Lydians may have been motivated by a desire to streamline their economic system and enhance economic stability. The introduction of coins allowed for a more efficient means of conducting transactions compared to barter or other forms of exchange.

It’s also worth remembering who regulated the Lydian coinage: their ruling class. The use of standardized coins with official markings and denominations could have provided a sense of stability and legitimacy to the Lydian rulers. It helped establish a formalized system of currency that reinforced the authority of the ruling elite.

Overall, it seems likely that the Lydians simply outgrew the old bartering system, the same way the Chinese were at around the same time. Coinage was easier to transport, had a standardized value, and was easier to regulate. It set a precedent that Lydia’s neighbors soon began to follow. We know, for example, that not long after the Lydians the Ionian Greeks had copied suit and began using their own form of coinage.

What did Lydian Coins Look Like?

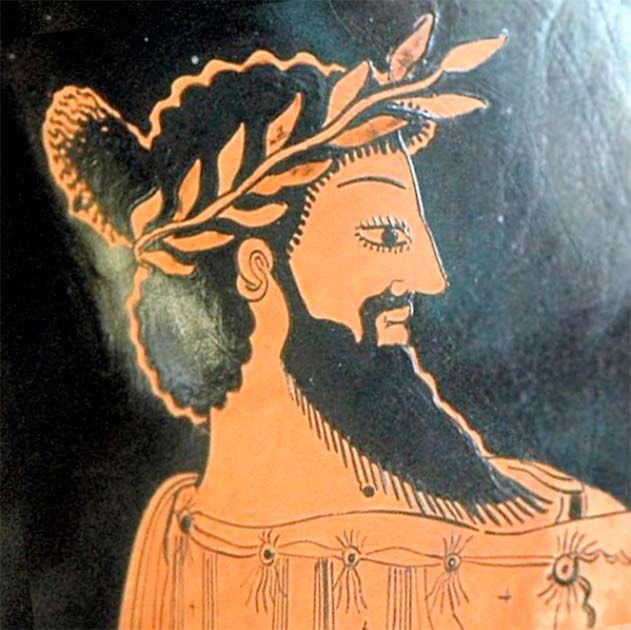

Compared to later designs the first Lydian coins, especially those coming from the reigns of kings Alyattes and Croesus, were relatively basic. The first coins were rather irregular in shape, reflecting the practice of cutting or stamping pieces from a sheet of electrum.

The upside of the stamping process was that it allowed the coins to feature stamped designs on one side. These designs varied over the years but were often simple geometric patterns, symbols, or images (like a lion or king’s head).

The opposite side featured something known as an incuse punch. This was a depressed area corresponding to the design on the obverse side. The stamped designs and incuse punch likely acted as anti-counterfeiting measures. Likewise, the standardized weight and composition of the coins enhanced their acceptance in trade, fostering confidence in transactions.

These coins may have been a little rough around the edges (literally) but there is no denying their impact on history. The Lydians, driven by practical pressures and a keen sense of economic foresight, had introduced a revolutionary concept that transcended their borders and quickly began inspiring neighboring nations.

The legacy of Lydia’s coins reverberates through time, shaping the very foundations of modern economies, and can still be felt today. From the symbolic electrum discs of ancient Sardis to the digital transactions of today, the journey of Lydia, wealth, and the first coins endures as a powerful reminder of the enduring impact of innovation on the fabric of human civilization.

Top Image: “What if, instead of something being valuable, we all agree it is valuable?” A Lydian electrum coin. Source: Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com / CC BY-SA 3.0.