Monotheism was a long time coming for the Roman Empire. Worship of the pantheon of gods, borrowed from the Greeks and renamed, was central to the Romans, lasting for centuries both before and after the birth of Christ.

Alongside the major gods, there were multiple, more specialized gods and their associated cults, which allowed for targeted worship. Romans could pray to the god of childbirth or the gods of the harvest, and in most cases the relationship was straightforward and clear.

But among these gods were stranger cults, mysterious to modern researchers in form and function. One such, perhaps the most interesting of all the Roman cult gods, was Mithras: The Soldier’s God.

Mithraism

Mithraism, or the Mithraic mysteries, was a Roman mystery religion centered around the god Mithras. It was popular among the Imperial Roman army from around the 1st century to the 4th century AD.

In many ways it operated like the modern concept of a secret society. It involved a complex system of multiple grades of initiation, built around ritual meals. Initiates of the religion were called the “syndexoi”, those “united by the handshake”.

Meetings of the Mithraic mysteries often occurred underground in temples called “mithraea”. These survive in large numbers across the old Roman empire, a testament to the wide reach this strange religion had.

Whilst it spread throughout the empire, the center of the mysteries appears to have been in Rome. From there, it managed to make it as far North to Roman Britain and as far south as the African colony of Numidia.

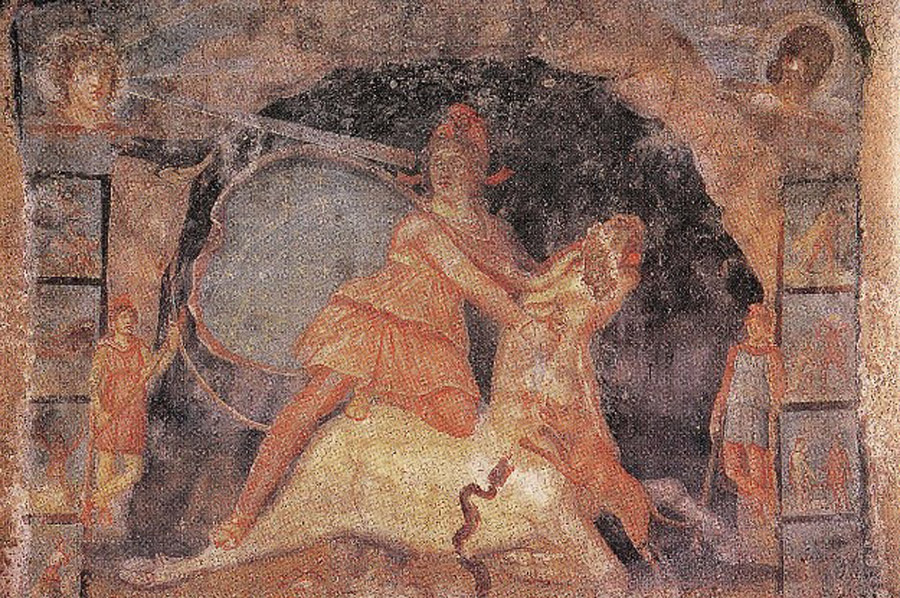

There have been numerous archaeological finds that have shown the popularity of this religion before the rise of Christianity led to its downfall in the 4th century. From these we are able to piece together something of the Mithraic narrative: iconic scenes of Mithras show him being born from a rock, slaughtering a bull, and sharing a feast with the Sun god, Sol.

Approximately 420 sites have brought materials to light about this cult. Around 1,000 inscriptions have been uncovered from the secret temples, as well as no less than 700 versions of the bull killing scene. 400 statues and other monuments have also been recovered, many of them obscure.

For this secret society did not record their religious practices, or their ceremonies. No written narratives or theology survive, and only limited information has been extrapolated from inscriptions and from passing mentions by the Greek and Latin literature.

- Zoroastrianism: the Religion of Fire that inspired the Hebrew Bible

- The Tophet: Was Ancient Carthage Driven to Child Sacrifice?

Even these snippets of information are contradictory and vague and it appears the authors, not themselves initiates, were as confused about this religion as modern day researchers are. Whatever the cult of Mithras was up to, it was behind tightly closed doors.

Who was Mithras?

The name Mithras is the Latin and Greek version of the Zoroastrian god Mithra, popular with the Persian civilization in the Iranian sphere. One of the earliest mentions of Mithras is found in the Greek work describing the life of the Persian king Cyrus the Great, the “Cyropaedia”.

However, the exact form of the Latin and classical Greek words varies and it appears that Mithra is only the starting point for Mithras worship. The form of the word “Mithras” has led to modern historians disagreeing about whether it even refers to a single god. It has been suggested, rather, that is refers to a custom, something associated with multiple gods.

A lot of the information that is known about Mithras is from the sculptures and reliefs that have been found by archaeologists. The prominence of the reliefs depicting a figure (presumably Mithras) slaughtering a bull suggest this is a central aspect of the religion. But the underground temples would not accommodate such an activity, and no sacrificial grounds to Mithras have ever been discovered.

In every mithraea that has been found, the centerpiece of the temple was the representation of Mithras killing a sacred bull, known as the tauroctony. It is presented either as a relief or free-standing but is always there. Mithras is seen to be clothed in Anatolian costume and wearing a Phrygian cap, prominent with the people of Eastern Europe.

The bull is presented as exhausted and is being held by its nostrils by a kneeling Mithras, but he is not the only person in the relief. As he slaughters the bull, he looks over his shoulder to the figure of the Sun god Sol.

All of this takes place in a cavern in which Mithras brought the bull, where he is also joined by the divine spirit Luna. The significance of the bull, the cave, and the presence of the gods, are completely unknown.

Rituals and Worship

Some modern historians see parallels with pagan midwinter festivals and estimated that the Mithraic new year was the 25th December. Others however disagree and claim that, as a secretive and underground cult, they had no such public ceremonies.

This would correlate with the theory that all new initiates were required to swear an oath of secrecy and dedication. The initial initiation apparently involved a symbolic asking of questions in which the prospective inductee had to answer correctly. However, no first-hand account of these rituals survives.

Archaeological remains indicate that many of the rituals of Mithras involved feasting. Many of the temples have had a plethora of artifacts for eating utensils, and food residue is often found.

These include animal bones and fruit residues. Interestingly, the common presence of cherry stones suggests that the feasting took place in mid-summer, another clue to a secret calendar.

Membership lists have also been found, and all of the names found on the lists were male, indicating that the cult was likely for men only. Soldiers were strongly represented among known Mithraists as well as merchants, customs officials, and minor bureaucrats.

Greek and Roman Mysteries

Whilst this may seem unusual to a modern reader, there were in fact many Greek and Roman mystery religions and cults. Some of the most famous of these mysteries include the Eleusinian Mysteries from centuries earlier, predating the Greek Dark Ages. They continued to flourish throughout the early centuries after Christ but were particularly popular in the mid-4th century.

After Emperor Constantine introduced Christianity as the main religion of the Roman empire, these mystery cults faced significant persecution from Christians. Cults such as that of Mithras stood in direct competition with Christianity and were seen as heresy.

However, that did not stop them from having an influence on Christianity as a whole. It seems that elements of Mithraism survive in Christian dogma to this day.

The first evidence comes in the form of linguistic changes. For example, whilst the rites of baptism and sacraments were well established in Christianity, they began to be referred to as “mysterion”.

This was a Greek term used for their own rites, and suggests that the concept of religious mysteries and initiates carried through from Mithraism to Christianity. This allowed Christians to not discuss their sacred rites with non-Christians who might misunderstand them or disrespect them.

In fact, some non-Christians in the Roman Empire thought that the secret cults and Christianity were very similar. So much so that throughout history, they have been associated with each other. Even in the 18th century, Charles-Francois Dupuis claimed Christianity came from the secret religions, a plausible argument that continues to provoke debate to this day.

What Can We Know?

But, ultimately, the problem for modern researchers is that the secret cults were so secretive. We do not know how they worshipped. We do not know what they believed. We only know the mystery.

The cult of Mithras can show us, however, the Roman habit of combining different religions and customs from all around their empire. Almost all of the Mithraea contain statues dedicated to other gods and as such, statues were found in other temples around Rome.

This suggests a degree of integration for Mithraists into Roman polytheistic worship. Mithras was not an alternative religion, but part of the civic religion practiced by many others and endorsed by the popularity of mystery cults at this time.

But this god of soldiers may keep the deepest of his mysteries forever.

Top Image: Golden-faced Mithras defeats the bull. Source: Bradley Weber / CC BY 2.0.

By Kurt Readman