The Nooitgedacht Glacial Pavements are a geological feature between the town of Barkly West and the city of Kimberley, in central South Africa. Formed some 300 million years ago during what is known as the Dwyka Ice Age, the passage of the glacier left a distinct and unusual pattern on the landscape.

And the landscape left behind with its distinctive flat surfaces scoured from the bedrock was evidently seen as important by the peoples who lived there. Many of the rock faces have strange depictions and artwork on them, scratched on the rock.

These rock engravings are something of a mystery. It is not clear who the artists were, and in several cases the pictures defy easy explanation.

Some outlines are recognizable as animals and human-like figures, but others are more abstract. Are these weird geometric shapes evidence of decorative art, or was there something else going on at these glacial pavements? And who were these ancient artists?

The Science Behind the Glacial Pavements

300 million years ago, the continents didn’t look like anything that they do today. Glaciers of the Dwyka Ice Age covered much of the Northen Cape belt, reaching across maybe a third of modern-day South Africa. These glaciers moved southwards, carving up the landscape behind them as they ground the bedrock beneath their crushing ice.

This led to the formation of the glacial pavements, where the huge rocks embedded the slow-moving ice tore through the 2.7 billion-year-old volcanic rock beneath. Once the rocks carried in the bedrock had done their work, the finer sediments in the base of moving glacier scoured and polished the new surfaces to the smooth finish.

When the glaciers retreated as plate tectonics pushed the landmass northwards towards warmer climes, these smoothed surfaces were exposed, creating a unique landscape. The glacial pavements are striations made up of a mixture of mud and rock, left behind by these glacial movements.

- Chaco Canyon Polydactyly: A Thousand-Year-Old Foot Fetish?

- Blythe Intaglios Geoglyphs in California’s Desert

It was these surfaces that the mysterious rock artists found so appealing and suitable for their art.

The Carvings

The carvings on the pavements, although similar in some of their subject matter to neolithic art elsewhere, have a unique texture and style. The engravings were produced by what appears to be pecking, where chips and flakes of the rock were broken away in small pieces.

This results is a particular textural effect where the art appears somewhat three dimensional. Much of the rock art is positioned in such a way that the viewpoint for observing it is clear, and given the slightly darker color of the newly exposed rock, the pecking action has been used by the artists to create areas of shadow.

The carvings seem to have been made with stone tools, which would suggest a stone age origin for the art. However another theory is that these were made much more recently, perhaps in the past 1,500 years.

Two peoples inhabit the area of the rock art: the Khoekhoe nomadic shepherds and the hunter gatherer San. Both have come to be known as the “world’s oldest people” and it is likely that the ancestors of one or both of these peoples were responsible for the rock art.

It may be that the San were responsible for the more straightforward animal depictions. The local large species of animals that they hunted would have been very important to the San, and it is indeed these animals, including rhinos, ostriches and bovines, are depicted.

But who carved the strange geometric carvings and other unusual depictions found at other points on the glacial pavements? These seem unlikely to come from the ancestors of the San as they are markedly different in location, composition and style.

Spirals and swirls can be found on various outcrops of rock on the pavements, as well as apparent depictions of bags, or items of clothing. The meaning of these depictions, and what they actually represent, are unclear.

Were the ancestral Khoekhoe, with their more peaceful and pastoral lifestyle, drawn to make these abstract depictions? Or were these attempts to depict something unfamiliar to modern eyes, which we misinterpret?

Oh, And There’s A River Of Diamonds

The ancient volcanic bedrock formed billions of years before the glacial action contained many gemstones, including pipes of material containing diamonds. When the Vaal river cut a path through the bedrock, portions of these pipes were exposed to the surface and diamonds were drawn into the sediment above.

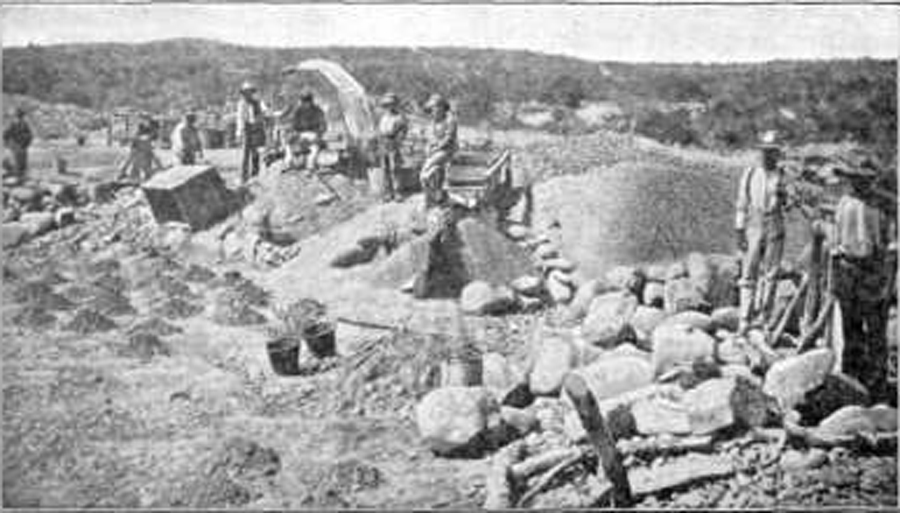

In the late 19th century these high quality diamond sands were discovered. Starting in 1869, the gravel banks of the Vaal river have been a fruitful source of diamonds. In one 32 year period between 1949 and 1981, the gravels produced over 80,000 carats of diamonds, including a 511 carat yellow gemstone known as the Venter Diamond.

Because of the action of the river, the diamonds were fairly straightforward to extract and could be done so by a single digger. One person was permitted to claim an area of 15 m by 15 m (49 foot by 49 foot) and the diamonds could be panned in a similar manner to gold, washed from the surrounding alluvial soil and gravel with the river water.

Even today, the search for diamonds continues around the Vaal River in areas near the towns of Barkly West, Delportshoop, and Windsorton, and the search has extended even further downstream. But the heavy bulk of diamonds are all extracted already, in the Nooitgedacht diggings in between 1949 to 1981.

Mysterious, but Protected

However the strange rock art in the area is protected from such destructive exploitation of the landscape. The rock art of the Nooitgedacht Glacial Pavements have been declared a national monument of South Africa.

So, while we may not understand what the art means, or even be certain as to who pecked the strange shapes out of the rock, we can be sure that future generations have a chance to ask the same questions for themselves. Maybe, in the future, an answer will be found. But for now, the art will remain undisturbed.

Top Image: Depiction of a cow at Nooitgedacht, “pecked” from the rock apparently by stone tools. Source: Keilmesser / CC BY 3.0.

By Bipin Dimri