A lust for everlasting life resulted in the massive Qin Shi Huang tomb.

At just thirteen years old, the boy-king, Ying Zheng (259 BCE – 210 BCE), began to construct his own tomb in today’s Lintong District, Xi’an, in China’s Shaanxi province. At the age of 38, King Zheng would unite all the warring states and become the first Emperor of China, ‘Qin Shi Huang.’ As the emperor’s power and wealth grew, so too did his obsession with his afterlife. He designed and constructed a mausoleum larger and more extravagant than the world had ever seen before. The Qin Shi Huang tomb and his surrounding 38 square mile necropolis would contain every single detail of the emperor’s luxurious life on earth, including a terracotta army to protect him – all of which he would take into the afterworld.

A Brief History of Qin Shi Huang

The Prince Becomes King

In 260 BCE, China was in a state of turmoil. Various feudal states divided the country, and the Warring States Period had lasted for 250 years. Seven individual kingdoms tried to establish their dominance and lay claim to the entire country. However, the strongest of these states was Qin. When King Zhuangxiang began his reign in September of 250 BCE, it appeared that he would become China’s first emperor. However, his reign was short-lived. After just three years in power, he died.

King Zhuangxiang’s heir was his young son named Ying Zheng. A regent served as temporary ruler until the young king was old enough to rule on his own. Ying Zheng exhibited traits from the very beginning that marked him as calculating and fearless. At the age of 21, he led a revolt against his regent who tried to maintain control. This culminated in bloodshed and removed every obstacle to the king’s reign.

‘Son of Heaven’ Unifies China

Despite multiple assassination attempts, the King of Qin managed one successful campaign after another until he defeated all rival states throughout the land. In 221 BCE, the warrior king accomplished something no other leader had. He united the kingdom and created the first Chinese empire. Although he was a harsh despotic ruler, he left behind important legacies: the Great Wall, a vast network of roads that connected his empire, and one system of weights, measures, money, and writing.

As he approached his 40th year, the king proclaimed himself ‘Qin Shi Huangdi,’ a name that conveyed his power as the first high-god (or godlike emperor) of Qin. According to Chinese belief, Zheng’s successes conferred upon him the mandate of heaven. As the ‘Son of Heaven’ he would rule from the center of the universe like a god. From this point, the emperor became obsessed with maintaining his divine power (and possessions) – even in the afterlife.

Preparations for Everlasting Life

The digging and preparation of Ying Zheng’s tomb had begun immediately upon his coronation as king around 246 BCE. As the king grew into a man and later became Emperor, he would amass more power and control than anyone had ever seen in the kingdom. Likewise, he acquired wealth and luxury beyond imagination. The power-hungry emperor wanted to take everything and everyone he needed to his next life. Thus, his engineering designs for his mausoleum became much more grandiose. However, he desperately feared death and hoped that he would never need his to use his mausoleum.

Qin Shi Huang embarked upon a mad search for the elixir of life. The legend about the Mountain of Immortality led him to travel three times to the island of Zhifu. He also built secret tunnels beneath his 200 palaces so that he could travel safely unseen, and he forced scholars, alchemists, and magicians to focus all of their attention on finding a cure for mortality.

In a bitter twist of irony, Qin Shi Huang died from drinking the mercury that he believed would make him immortal. Ultimately, he could not cheat death and would need his mausoleum after all. Slave laborers had worked day and night for three decades and would not complete the necropolis until 208 BCE, almost two years after the emperor’s death at age 49 in 210 BCE.

Construction of the First Emperor’s Mausoleum

Designers intentionally built the mausoleum to resemble the capital of Qin, Xianyang. It includes both an inner and outer city, divided by two distinct walls. Archaeologists believe that Qin Shi Huang’s tomb lies in the southwest of the inner city under the mound where it faces east.

Sima Qian claimed that 700,000 men, including slaves, built the emperor’s mausoleum. Some historians have pointed out that no city from that period of history had such a population. Hence, they speculate that sixteen to twenty thousand laborers may be a more accurate assessment. Regardless of the number, it is certain that those peasants and slaves met a tragic end. Archaeologists found mass burial pits around the mausoleum site piled high with the bones of builders. Some of them were still wearing metal shackles.

Additionally, scholars theorize, based on clues left by Sima Qian, that the craftsmen who had worked on mechanical devices designed to prevent entry into the burial chamber were put to death. They had observed the treasures in the Qin Shi Huang tomb and could not be trusted with those secrets. Once they placed the emperor deep inside the tomb, another group sealed off the passage, probably leaving behind anyone who knew the location of the emperor.

Within the Mausoleum Grounds

Forty years of archaeological studies of the mausoleum site have revealed that Qin Shi Huang intended to design his afterlife to match his life on earth in every respect. This included his imperial court life and the external environment that surrounded his city.

Animals and Royal Court

Near the outer wall of the greater mausoleum complex, a discovery of a royal park included bronze swans, ducks, and cranes, along with an entire suite of musicians. A horse stable discovered outside the outer walls contained horse skeletons and their terracotta caretakers. Altogether, there were roughly 300 coffins containing horse skeletons. Inside the inner wall, another pit contained the emperor’s terracotta attendants and government officials.

Additionally, in 1980 two chariots were discovered in passageways that appear to lead to the innermost walls of the Qin Shi Huang tomb under the burial mound. Each chariot was attached to four bronze horses. “According to the Han Dynasty scholar Cai Yong (蔡邕 132-192), the first chariot was for clearing the road for the Emperor’s entourage, and the second was his sleeping chariot. The bridles and saddles of the horses are inlaid with gold and silver designs and the body of the number 2 chariot has its sliding windows hollow cut” (Exploring Chinese History).

Close to the mound of the Qin Shi Huang tomb, scientists also found a mysterious pit of partially unclothed statues. Recent examination indicates that they were an entire imperial court of musicians, acrobats, and weightlifters designed to ensure the first emperor would have entertainment in his next life.

Concubines

In addition to the imperial court, archaeologists found pits within the mausoleum complex containing the skeletal remains of young females. The scientists believe they were the emperor’s concubines. Evidence suggests foul play, as dismembered body parts lay strewn about along with some scattered pearls and gold jewelry. These were not proper burials. According to Sima Qian, the usurper of the emperor’s successor ordered the death of the concubines. In theory, this would have prevented any unborn challenges to the throne.

Imperial Palace

In 2012 archaeologists announced the largest underground complex discovered so far within the Qin Shi Huang tomb necropolis. It is an entire courtyard palace and is roughly 170,000 square meters. This equals about 42 acres. The palace grounds contain one main building that overlooks 18 other royal houses, walls, roads, brickwork, and pottery shards.

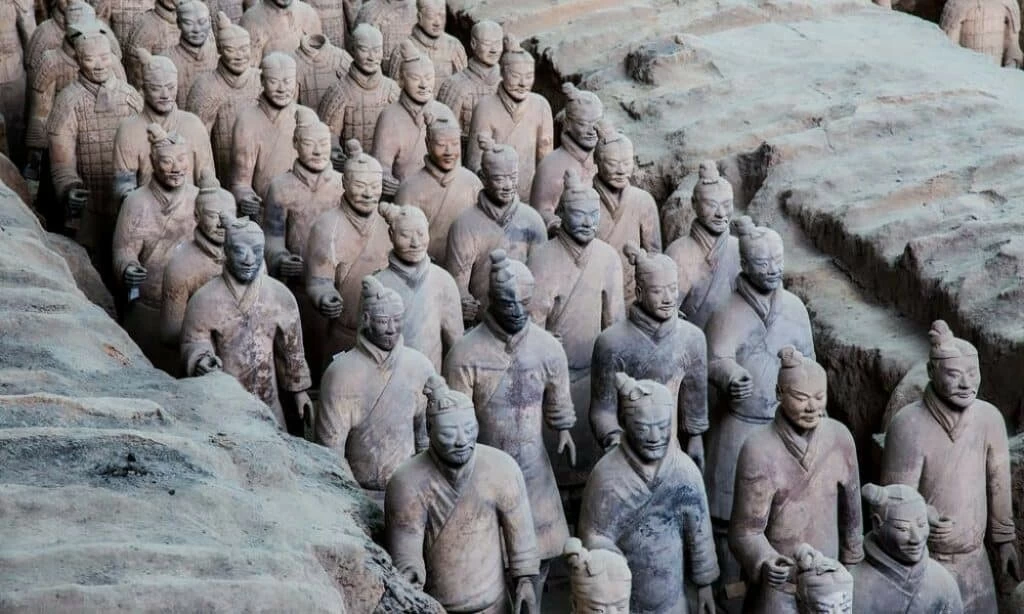

The Terracotta Army

About a mile east of the tomb, a hallmark discovery occurred when local villagers of the Lintong county embarked upon digging a well in March of 1974. Approximately six feet below ground, the villagers unearthed terracotta fragments and bricks.

Soon after the discovery, archaeologists began excavations. To date, they have identified three separate pits that contain about 8,099 terracotta statues of warriors, weapons, and horses with their chariots. Many of the statues were badly damaged, and scientists reconstructed only about 2000 of them so far. Experts estimate that it may take another 50 years to complete the excavation project.

Presumably, the purpose of the Terracotta Army was to protect the emperor from his enemies in the afterlife. Interestingly, the pits are located between the emperor’s tomb and what was enemy territory. Additionally, the soldiers stand in battle formation facing east toward the kingdoms he conquered.

The pits contain infantrymen, cavalry, and high-ranking officers, in addition to their horses and weapons. Each statue reveals exquisite details in hair and battle regalia, and each face holds different expressions and features. Some experts believe that the sculptors of the Terracotta Army designed them as exact likenesses to the best warriors that existed in Emperor Qin’s real army.

Nothing of the likes of the Terracotta Army has ever existed in China before. It is uncertain who crafted the statues, however, scholars theorize that Hellenistic Greek sculptors may have taught the artists under Emperor Qin. Today, the statues still stand in their original corridors, and the whole site has been enclosed in a museum where visitors can see the army.

You May Also Like: Terracotta Army: Eternal Sentinels of Qin Shi Huang

The Tomb

At the center of the enormous necropolis lies a pyramid mound that was once 350 feet high. Workers constructed the mound by packing dirt into the shape of a pyramid, shown below. Archaeologists believe there is an underground palace below the mound surrounded by walls that are about 4 meters high. The Qin Shi Huang tomb lies at the center of the mound, indicated with the bright white spot. However, experts are uncertain exactly how deep the tomb chamber is. Estimates place it between 20-50 meters below the surface. The chamber itself is still undisturbed.

Historical Records by Sima Qian is the first written documentation about the first emperor’s tomb:

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Sima Qian”]The site includes three streams, and his coffin is encased in a bronze sarcophagus. The floor of the central burial chamber floats on rivers, lakes, and seas of mercury…The vaulted ceiling is inlaid with pearls and gems to emulate the sun, moon, and principal stars of the constellations in the night sky. Whale oil lamps are brightly lit for an everlasting effect of illustriousness.[/blockquote]

Using modern scientific techniques, scientists have revealed details that may confirm the historical record of Sima Qian. As noted, Qian wrote that designers of the tomb used mercury to create simulations of rivers and seas in the tomb. Archaeologists have detected extremely high levels of mercury in the area. Additionally, imaging and other tests revealed the presence of a vast amount of metal within. This also affirms Qian’s account that the emperor took his treasures with him.

Why the Tomb Remains Unopened

There is an ongoing debate in China that has delayed the complete excavation of the Qin Shi Huang tomb. Some people maintain that an excavation is immediately necessary due to the potential for seismic activity in the region. However, others argue that China does not yet possess the technology or ability to carry out the exploration properly. There is also trepidation, as stories tell of entryways that have booby traps to prevent access to the tomb, and high levels of mercury could pose a health risk.

A World Treasure

With over 600 archaeological sites, including the stunning Terracotta Army, the Qin Mausoleum is a magnificent historical treasure. The ancient artifacts can tell us about the sculpture, engineering, rituals, entertainment, military personnel, rank, and strategy, and the deeply held beliefs of the people who lived more than 2000 years ago. In 1987, UNESCO declared the Qin Shi Huang mausoleum and the Terracotta Soldiers a World Heritage Site due to their immeasurable testament to the rich history of China.

You May Also Like: Secret Tomb of Genghis Khan

Additional references:

BBC

Updated by Historic Mysteries on January 18, 2018