For many situations, the best way to trace how our ancestors moved across ancient Eurasia is through the languages they spoke. Often, a commonality of language or evidence of frequent loan words can reveal a trading relationship and an association between two peoples which would otherwise be missed.

The Indo-Iranian language family is the southeasternmost branch of the Indo-European languages. This branch of language includes 300 languages, is spoken by around 1.5 billion people, and spans the Caucasus, South, Central, and Western Asia.

During the Middle Bronze Age, the language that is believed to have been spoken was the Proto-Indo-Iranian language, the ancestor of the modern Indo-Iranian languages. One group of early peoples that likely spoke this ancestor language are the members of the Sintashta culture.

This culture was known for its skills with horses, metallurgy, and the creation of complex cities. But, most of al, they were known for their use of an extremely unusual tool of warfare for steppe warriors. The Sintashta were charioteers.

The Sintashta Culture

The Sintashta culture (Синташтинская культура) was a late Middle Bronze Age archeological culture that existed sometime around 2200-1900 BC located to the west and east of the Southern Urals. The culture is named after the Sintashta archeological site in the Chelyabinsk Oblast of Russia, but these people spread much further than their capital: through the Orenburg Oblast, the Republic of Bashkortostan, and into Northern Kazakhstan.

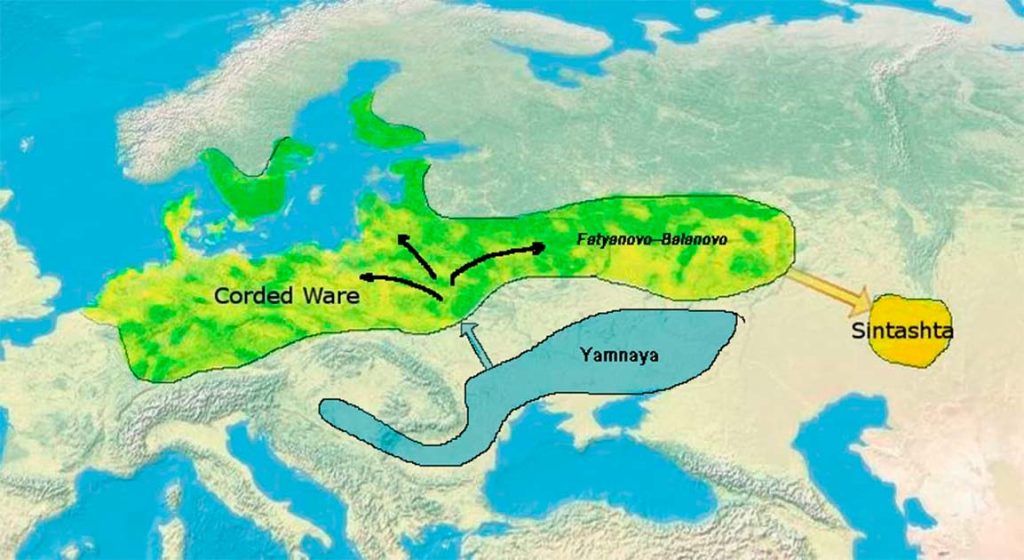

The Sintashta culture is believed to demonstrate the “Eastward migration of peoples from the Corded Ware culture.” The Corded Ware culture, one of our oldest civilizations which existed between 3000 BC-2350 BC, spanned a large area of Northern, Central, and Eastern Europe.

The Sintashta culture is closely associated with the origin of Indo-Iranian languages. It is believed that the people of the Sintashta culture spoke Proto-Indo-Iranian (the ancestor to the Indo-Iranian linguistic family). Archeologists and linguists support this belief due to similarities between The Rigveda, a religious text containing hymns in Vedic Sanskrit.

The culture is primarily associated with a single archeological site: the remains of a Bronze Age fortified settlement and city with a distinctive use of metallurgy. At a time when many humans were nomadic, the Sintashta culture, it would seem, created permanent settlements.

The settlement consisted of around 50 or 60 rectangular homes, all built in a circle with a diameter of 140m. The circle of homes was surrounded by a large earthen wall reinforced with timber. The Sintashta River, which leads to the Tobol River in Siberia, has shifted over time and destroyed half of the Sintashta archeological site; only the remains of 31 homes are visible.

But what survives is enough to tell us how strange this culture was. Metalworking was a part of this culture to an unprecedented level, and every part of life was intertwined with bronze.

Archaeologists have found evidence that strongly suggests that both copper and bronze metallurgy occurred in every home at Sintashta. The economy likely revolved around their copper metallurgy skills.

Copper ores, plentifully available from mines near the site, were brought to Sintashta to be processed into copper and arsenical bronze. Arsenical bronze is created when arsenic, rather than tin, is combined with copper to create bronze.

Arsenic is a poison, and the creation of arsenical bronze impacted the Sintashta’s health. Arsenic is vaporized at 1139°F (615°C), and as it was being melted and even during casting, the arsenic was releasing arsenical oxide around all working with the metal, so basically everyone.

Arsenic oxide attacks the eyes, skin, lungs, and nervous system of those exposed to high levels. Chronic arsenic poisoning leads to weakness in the legs and feet, also known as peripheral neuropathy.

Due to the size and complexity of the Sintashta culture’s fortifications, it is believed that metallurgy was occurring at what would be considered an industrial level. Every building excavated at the Sintashta sites has remnants of slag and smelting ovens.

Chariots

The chariot reinvented the art of warfare and was widely used throughout Eastern Europe for centuries. The Sintashta culture was well known for their use and attachment to horse-drawn chariots.

Burial sites associated with the Sintashta often show signs of elaborate funerary rituals in which the deceased would be buried with their ornaments, horses, weapons, and in many cases, their entire chariot. An archeologist from Hartwick College in Oneonta, New York, used radiocarbon dating to find the age of the horse’s skulls buried with the chariots.

Astonishingly, the skulls dated around 2000 BC, meaning the chariots are around the same age. This is significant because it implies that chariots were created and used two hundred years before they appeared in the Middle East, where they were believed to have originated from.

Evidence now suggests that the chariot’s invention and use occurred along the great Eurasian steppes. It was the steppes, not the heartlands of Mesopotamia, who first conceived of chariot warfare.

The chariots used by the Sintashta culture are, however, very different from ancient Middle Eastern chariots. The Sintashta chariots were only wide enough for one person, and Middle Eastern chariots could fit up to three people. The wheels of the Sintashta’s chariots had between 8 and 12 spokes as compared to the four spokes on Middle Eastern wheels.

But the main problem is that the chariots of the Sintashta culture are not really suited to the environment in which the Sintashta found themselves. The steppes have always been known for their skilled horsemen, and the landscape through the Urals, even today, is challenging to navigate through.

So why would a culture with exceptional riding skills add a chariot, which would only slow a horse down? The answer to this question may lie within the pages of the 3,000-year-old Rigveda. The religious text is a compilation of hymns from the Aryan people, horsemen that invaded India from the north. The hymns in the Rigveda describe, in great detail, traditional Aryan rituals.

While the Sintashta culture existed one thousand years before the Rigveda was written, their burial rituals are identical to what the Rigveda describes. Warriors were buried with their horse(s) and their chariots.

The deceased is placed behind the chariot, and holes have been dug into the ground for the wheels to fit in; then the horses are next. Several planks are placed over the bodies and chariot, and a ritual sacrifice of horses and one goat takes place on the planks.

The hole in the ground is filled over with earth, and a mound is created above the ground. Once the mound is complete, the same animal sacrifice is repeated.

The fact that the Sintashta culture did exactly the same practices described in the Rigveda is eerie. If we continue to look at the Rigveda, the chariot is the vehicle of the gods, and there are many tales of chariot races. Is it possible that the Sintashta people were the ancient ancestors of the Aryans?

What happened to the Sintashta?

It is believed that the Sintashta culture ended due to expansion. Most of the metals produced by the people were exported to the many cities of what is known as the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) of Central Asia.

Due to the trade routes from Central Asia reaching the steppes, the Sintashta had access to travel to other urban civilizations, of places like Mesopotamia and modern Iran. The trade routes allowed horses, chariots, and the Indo-Iranian-speaking peoples of the Sintashta culture to enter the Near East.

Top Image: The Sintashta were expert metalworkers with a forge in every home, and were also using the chariot as a weapon of war centuries before Mesopotamia. Source: Омурали Тойчиев / Adobe Stock.

References

Tkachev, V. 2020. Radiocarbon chronology of the Sintashta culture sites in the steppe Cis-Urals. Rossiiskaia arkheologiia. Available at: https://ras.jes.su/ra/s086960630009071-7-1-en

Linder, S. 2020. Chariots in the Eurasian Steppe: a Bayesian approach to the emergence of horse-drawn transport in the early second millennium BC. Antiquity, 94-374. Published online by Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/chariots-in-the-eurasian-steppe-a-bayesian-approach-to-the-emergence-of-horsedrawn-transport-in-the-early-second-millennium-bc/C4FDF8C5E7D1D20A28BEB7F6C50A9AF4

Chechushkov, I. 2018. BRONZE AGE HUMAN COMMUNITIES IN THE SOUTHERN URALS STEPPE: SINTASHTA-PETROVKA SOCIAL AND SUBSISTENCE ORGANIZATION. University of Pittsburgh. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/37201120/BRONZE_AGE_HUMAN_COMMUNITIES_IN_THE_SOUTHERN_URALS_STEPPE_SINTASHTA-PETROVKA_SOCIAL_AND_SUBSISTENCE_ORGANIZATION