The Bayeux Tapestry is one of the most important artifacts that has survived from Medieval Europe. It’s both a work of art as well as a historical document. It measures over 70 meters long and 20 centimeters tall.

The embroidered masterpiece tells the story of William Duke of Normandy’s invasion of England in 1066 and how he became “William the Conqueror.” The Norman conquest of England was one of the most significant events in European history. The Bayeux is a suitably grand masterpiece that has attracted both scholars and tourists for centuries.

A Remarkable Tapestry

Medieval tapestries served a variety of functions. In a time before central heating, tapestries hanging on walls provided a form of insulation against European winters. But since they were so expensive to produce, they were reserved for royalty and the nobility.

As a form of visual art, elites use tapestries both for decoration and as status symbols. Tapestries commonly depicted religious imagery and events from the Bible. Elites would use them to advertise their piety. Tapestries could also portray important events from their lives or their family’s history, often designed to advance a specific narrative.

But the Bayeux Tapestry is unique. It’s the biggest and longest surviving tapestry from the medieval period. Unlike most tapestries from this era, the Bayeux Tapestry was hand-embroidered on linen with woolen thread and not woven. It consists of some 70 different scenes chronicling the Norman invasion events, with Latin tituli, or labels, narrating the events. Finally, it’s one of the earliest examples of Romanesque art that depicts a secular event.

The Bayeux Tapestry is also one of the few primary sources, or nearly primary sources, that tells the story of the Norman conquest. Although its exact origins are unknown, it was most likely commissioned a few years after the Battle of Hastings.

Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, the half-brother of William the Conqueror, most likely ordered it. As such, it tells events from a Norman point of view. While it does offer the most detailed description of the war between the Normans and Anglo-Saxons of any source, its inherent bias means that it can’t be considered entirely accurate as a chronicle of history.

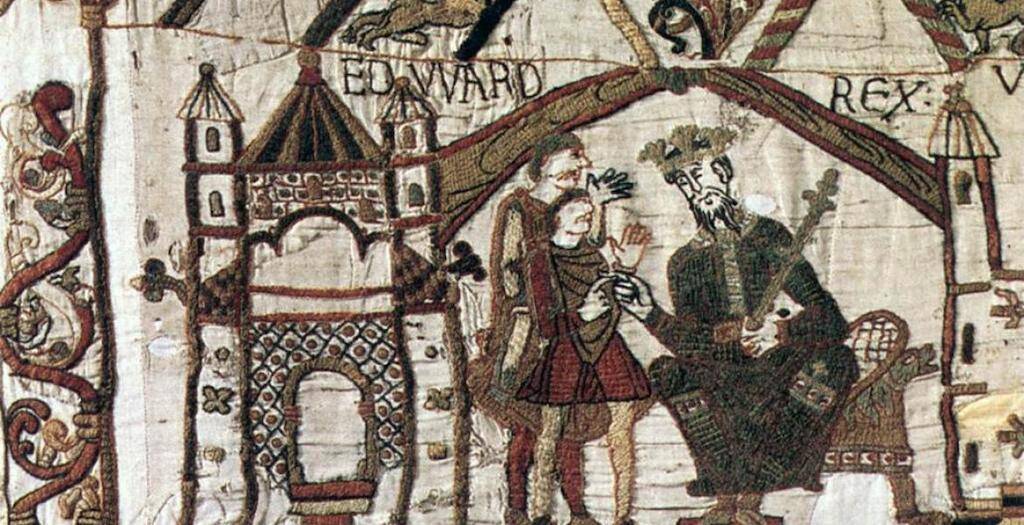

Three Claimants To The Throne

Within the Bayeux Tapestry, the narrative told begins in 1064 CE, two years before the decisive Battle of Hastings. Around this time, King Edward the Confessor of England was about 60 years old. His exact birth date is unknown and he had no children. This wasn’t itself a problem. At this time, English kings did not inherit the throne. Instead, the king and the most powerful Anglo-Saxon nobles would choose the king at a council called the Witenagemot. But as Edward declined, three rivals to the throne emerged.

– William the Conqueror

William was the illegitimate son of Robert I, Duke of Normandy, and a tanner’s daughter. Born around 1028 C.E., William inherited the dukedom upon his father’s death at age seven. Initially known as “William the Bastard,” he ruled the French-speaking Norman duchy in northern France. He was also a distant cousin of Edward the Confessor. According to Norman historians, Edward had promised William the throne in 1051. In 1066, he was 39 years old.

– Harald Hadrada

Harald Hadrada was the King of Norway and a Viking warlord. He had previously been a soldier of fortune who fought his first battle at age 15. He served across Europe, the Mediterranean, and North Africa. Harald also married the daughter of a Russian czar.

Years earlier, Harald had maneuvered to inherit the kingdom of Norway from Magnus I. Magnus’s predecessor, Cnut the Great, established a mighty Viking “North Sea Empire” that included England. Cnut ruled England from 1017-1035, and through this connection, Hadrada would make his claim on the English crown.

– Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson was the most powerful and influential Anglo-Saxon noble in England, even more powerful than the king himself. Godwinson was a capable military commander and politician but had no royal lineage. However, his sister Edith married King Edward. On his deathbed, Edward apparently made Godwinson his heir, breaking his promise to William. Harold became King of England in 1066 at age 44, but his crown was by no means secure.

Chronicle Of The Invasion

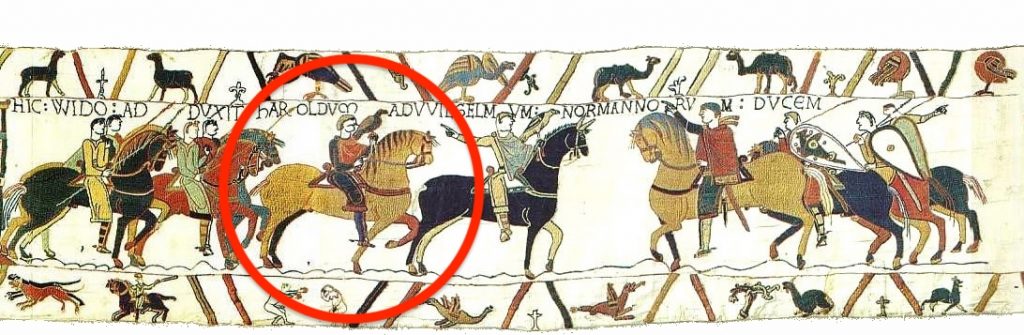

At the beginning of the tapestry, King Edward sends Harold Godwinson to Normandy to meet with Duke William. Along the way, he shipwrecks, and William rescues him. In Normandy, Harold swears an oath to William. Although the tapestry doesn’t specify what the oath was about, it’s believed to be a promise to recognize William’s claim to the English throne.

Harold returns to England, where one year later, King Edward is on his deathbed. Here, Edward makes Harold his heir. Harold subsequently becomes crowned king. Shortly after, Harold and his subjects fearfully watch a comet cross the sky. It’s believed this is a representation of Halley’s Comet—and a bad omen for Harold.

At this point, the Bayeux Tapestry diverges from the historical record. In reality, upon King Edward’s death, Harold Hardrada launched an invasion of England with 300 ships. The newly crowned King Harold and his army meet them at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. The Anglo-Saxons won a decisive victory over the Vikings.

The battle is considered to be the end of the Viking Age. But crucially, it weakened King Harold’s army before its showdown with the Normans. The Bayeux Tapestry omits this, most likely to avoid diluting William’s eventual victory.

The Tapestry continues with William receiving the news that Harold Godwinson has broken his oath and become king. William’s brother, Bishop Odo, orders the construction of a massive invasion fleet. The Normans sail to Pevensey, England, and land unopposed. At nearby Hastings, William builds a wooden motte and bailey castle. This marked the first occasion that a castle was built on English soil.

Battle of Hastings

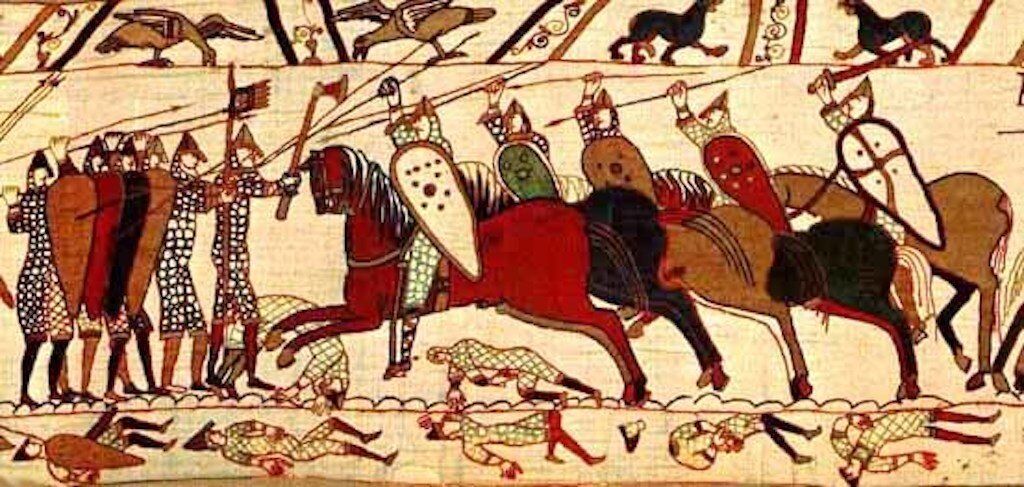

The Tapestry climaxes with the Battle of Hastings fought on 14 October 1066. In the tapestry, the Normans are depicted as mounted knights while the Anglo-Saxons fight behind a shield wall. At one point, William falls from his horse, but gets up, removes his helmet, and reassure his men. Finally, King Harold dies, receiving his just comeuppance for breaking his oath. Although historians haven’t definitively identified Harold in this scene, it’s believed that he’s killed by an arrow through the eye.

The tapestry ends as the Anglo-Saxons flee the battlefield. The Tapestry has lost some additional scenes at the end of the narrative, though it’s possible they depict William’s coronation.

Who is Aelfgyva?

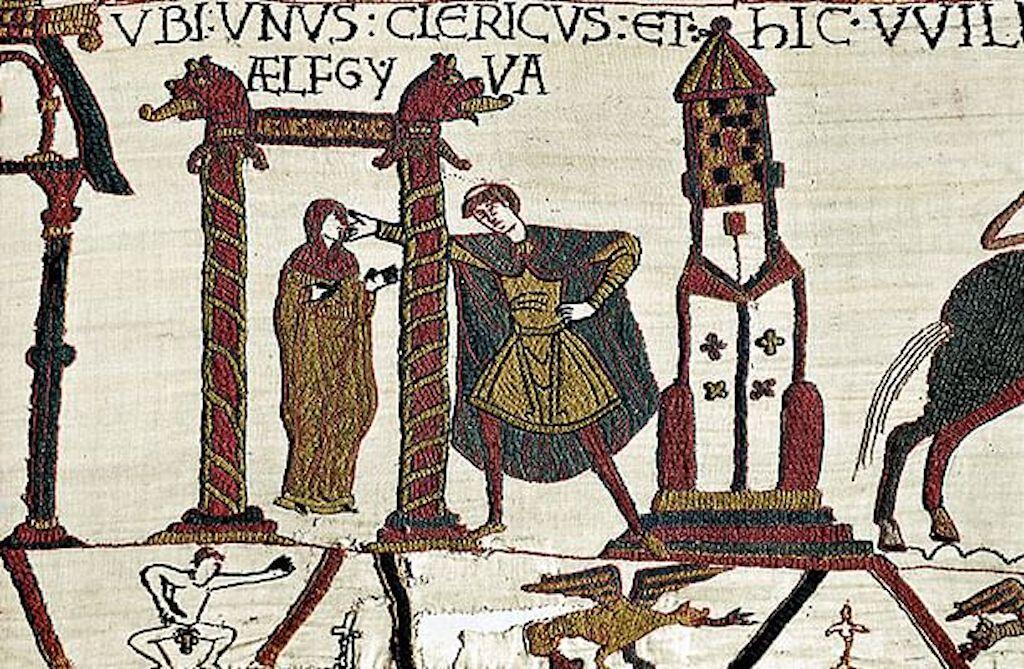

An enduring mystery lies near the middle of the tapestry. In it, there is a figure of a woman in a robe and head covering. To her right, a man with a tonsure reaching out and coming into contact with the woman’s face. To the duo’s right is a tall building that may be a church or a tower.

The incomplete caption, translated from the Latin, says, where a certain cleric and Aelfgyva. These two figures have stumped scholars and experts for centuries. They do not appear again in the tapestry. Researchers have been unable to identify Aelfgyva” as anyone in the military or royal history of the time.

Bayeux Tapestry After 1066

It was created between 1066 and 1079 CE, most likely for Bishop Odo of Bayeux. Rebuilt in 1079, the Cathedral of Bayeux most probably displayed it then. The Tapestry appears in the historical record following a cathedral inventory in 1476 CE. It most likely displayed there yearly for centuries.

In 1792 CE, during the French Revolution, the state confiscated the tapestry. Napoleon brought it to Paris to use as a propaganda tool against his British enemy. It returned to Bayeux in 1824 for display in the public library. It became a tourist attraction in the 19th century. During World War II, it remained in the Louvre for safekeeping, and then returned to Bayeux once again.

You May Like: The Shugborough Inscription

In 2018, France agreed to lend the Bayeux Tapestry to England for display in the British Museum. The lease is planned for some time in the future. When it leaves France, it will be for the first time in 950 years.