Ask almost anyone to name a Stone Age calendar in the British Isles, and the answer you will almost certainly receive is Stonehenge. But in truth these islands are filled with neolithic structures, which dot the landscape and which serve as mute testament to the strange, lost world of the pagan druids.

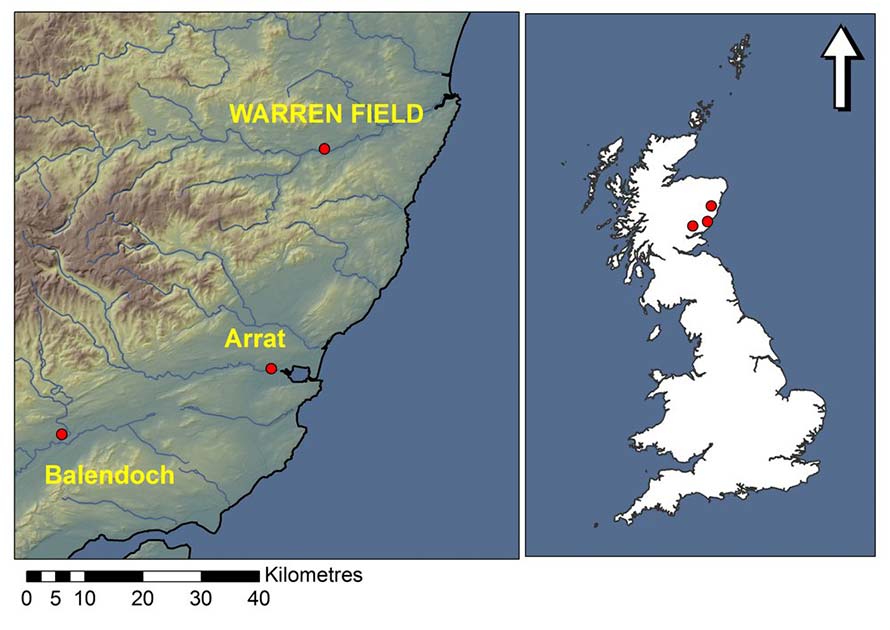

And now, following a discovery in 2005 and research by the University of Birmingham, led by Vince Gaffney, a professor of Landscape Archaeology and Geomatics, claims that oldest of such calendars has been found, in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. But what is striking about this site is just how old it is.

The site, known as Warren Field (because that’s where it is), may be tens of thousands of years old. If this is true, it would mean the origin of timekeeping may stretch back further than the emergence of the earliest formal calendars, which have been attributed to around 3,000 BC.

The Record of Time-Keeping

In the 60s and 70s, an American scholar named Alexander Marshack claimed that a small number of markings on objects from the Upper Palaeolithic were deliberate depictions of the Moon waxing and waning. These particularly came from the area of the Dordogne region of France.

The most iconic version of this is the Abri Blanchard bone plate. Marshack argued that the carvings, dating from around 30,000 BC, would have served as crude calendars. However, more modern thinking believes that these engravings are tallies of lunar events and only represent observations of lunar events as they unfolded rather than any version of predicting future events.

Much more clear evidence for a formal lunar calendar dates from the 3rd millennium BC and comes from Babylon. This is not surprising due to that area being the intellectual powerhouse and the beginning of civilization.

However, this new evidence that has been found in Scotland indicates that this may not be the case. The Scottish may have mastered time recording thousands of years earlier.

- Adam’s Calendar: A 300,000-Year-Old Alien Site in Africa?

- The Bodies of Stonehenge: Britain’s Largest Ancient Cemetery?

There is little doubt that early civilizations would have been able to make observations about lunar activities. Marshack’s work reveals this, and it proves that hunter-gatherer populations were at least watching the skies if nothing else.

It is also massively unlikely that roaming hunting parties would have been blind to or uninterested in the opportunity to plan ahead. Hunter-gatherers from the Mesolithic era (in Britain this period is between 10,000 BC and 4,000 BC) would have greatly benefited from being able to plan ahead with things like seasons and weather in mind, information that they could gain from observing the skies.

There is a swathe of evidence for seasonal migrations and gatherings of Mesolithic groups. A great example is Vespasian’s Camp near Stonehenge and at Star Carr. These are becoming increasingly investigated by archaeologists.

Careful study of these sites has revealed that these gatherings and comings together were much larger than anticipated. This could be for several reasons. It could be ritual, celebratory, or political based on marriages and alliances.

However, getting the timing right for these gatherings would have been severely important to the populations. They would need to ensure that there would be plenty of resources in the local area to sustain them and the extra mouths that they had to feed. Put simply, if you want to organize this many people, you need a calendar that everyone is working from.

Lunar Tracking and Warren Field

While the phases of the Moon are a great way to create 29 to 30-day blocks of time, this does not allow for predictions of the seasons changing. Due to the Earth orbiting the Sun, which is more responsible for the seasons, the lunar cycles do not always coincide with the change of the seasons or a set number of lunar cycles.

The Moon tends to go between 12 and 13 cycles per each solar year. This means that tracking seasons using the lunar cycle only will lead the interpreter to get gradually further from the truth as the year goes on.

The interpreter would need to know when to add and subtract an extra month to align with the solar calendar. However, if they were to have this information, it would be relatively straightforward to ensure that the lunar calendar does not stray too far away from the truth. It is this, that that Vince Gaffney and his team believe they have found in Aberdeenshire at the structure named Warren Field.

- The Mayan Calendar Facts, Theories and Prophecies

- Who Made the Nebra Sky Disc, and Why Did They Look to the Stars?

Warren Field is the location of a calendar monument suspected to have been built in 8,000 BC. It was first detected around 1976 during an incredibly hot and dry summer.

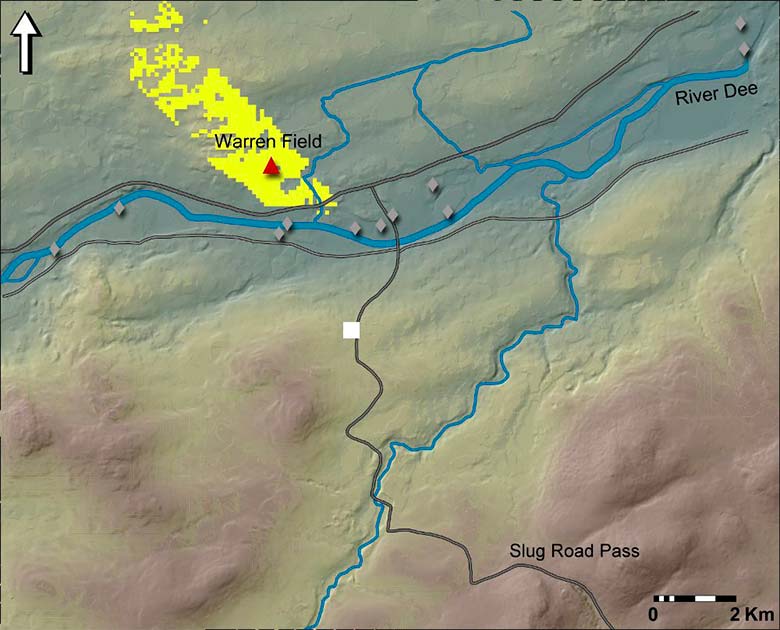

The visible feature revealed a set of 12 pits following a gently curving arc on the sloping ground near the valley of the river Dee. The alignment created by the pits stretches to around 50m (165 feet) long.

The pits seem to have evolved over several centuries and were fully developed around 7,800 BC. This predates Britain’s first farmers by almost 4,000 years. It indicates that hunter-gatherer populations were constructing permanent monuments which was thought not to be the case.

Whilst this is not the largest monument found in this era, the monuments are substantial enough to scar the earth in the same way that prolonged farmwork would do. It was always suspected that the pits had been the handiwork of settled farmers because a Neolithic hall had been found there and it was assumed that the pits would be associated with it. However, radiocarbon dating has shown that the pits originate from the Early Mesolithic period: still old, just not that old.

Gaffney’s team has thus demonstrated that the pit configuration in partnership with the landscape could have accurately tracked the seasons. It would act as a primitive calendar and would be the earliest device to be found to date anywhere in the world.

How Did it Work?

It was not only the revelation about the date that attracted Gaffney to the site. Of the 12 pits, they are all slightly different sizes with the smallest two lying at either end of the alignment. The pits themselves did not contain any indication of posts but instead held burnt material and stones from a fair distance away.

Whilst it could be argued that the pits represent the 12 months in the year, the 12 pits would not deal with the constant problem of the lunar calendar not aligning. However, archaeologists have noticed that the positioning of the pits acts as a natural reset for the monument.

The midwinter solstice occurred perfectly in the notch on the horizon which could be seen from the nearby pass. It created a fixed point which allowed for the population to reset their calendar and to keep it aligned. And just like that, you have a calendar.

Top Image: How the Warren Field calendar works with the surrounding landmarks. Source: Gaffney, V., Fitch, S., Ramsey, E., Yorston, R., Ch’ng, E., Baldwin, E., Bates, R., Gaffney, C., Ruggles, C., Sparrow, T., McMillan, A., Cowley, D., Fraser, S., Murray, C., Murray, H., Hopla, E. and Howard, A. 2013 Time and a Place: A luni-solar ‘time-reckoner’ from 8th millennium BC Scotland, Internet Archaeology 34. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.34.1, / CC BY-SA 3.0)

By Kurt Readman