As the deafening roar of bombs echoed across Europe and the Nazi war machine began to falter, Hitler and his loyal followers were driven to the brink of desperation. Desperate times called for desperate measures, and the Nazis greenlit a series of plans that had once been deemed too ambitious or impossible.

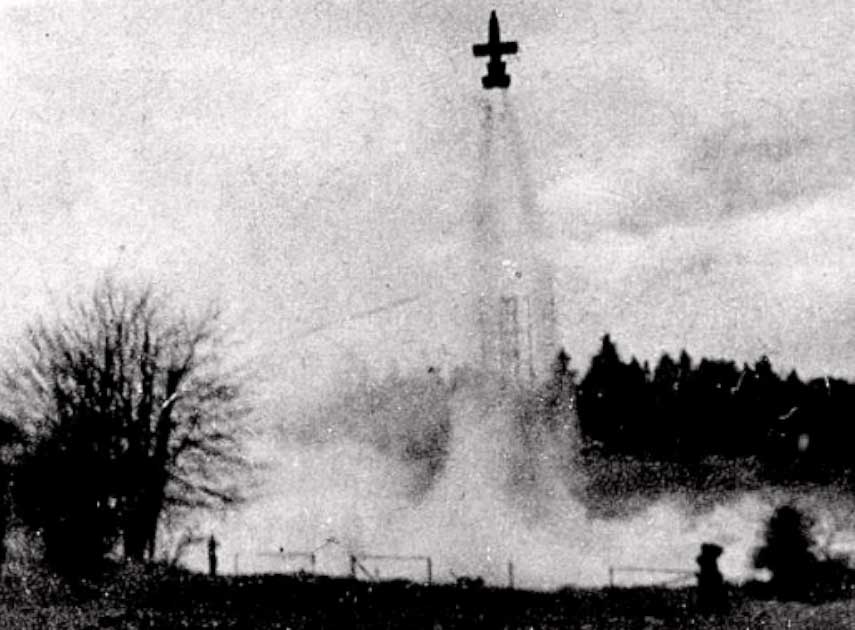

Among these daring endeavors was the Bachem Natter, also known as “Project Viper.” This was an audacious attempt to build the world’s first manned, rocket-powered, vertical take-off interceptor. It was a bold gamble, one that pushed the limits of technology and engineering to the brink, and ultimately ended in failure.

But despite this, the project would go on to leave a lasting legacy, as the revolutionary technologies developed during its creation would go on to shape the future of the aerospace industry. So why did the Germans need the Natter and with a little bit more time could it have worked?

A Game Changer?

Project Natter, also known as the “Natterscharm” was the brainchild of Dr. Werner von Braun who first proposed the project in 1939 but was quickly shot down by the German Air Ministry, the RLM. His idea was for a vertical take-off and landing jet fighter (VTOL).

He wanted to build a plane that could take off and land vertically, much like a helicopter but which had the speed and performance of a fighter plane. He dreamed of an aircraft that could be launched from a special trailer, rapidly gain altitude, and then engage in air-to-air combat with the enemy.

The Natter was a small, single-seat aircraft that was powered by a single rocket engine. It featured a unique design with a triangular-shaped fuselage and a vertical tail fin that doubled as a launch ramp. It had tricycle landing gear which allowed for vertical take-offs and landings.

The pilot sat in the cockpit at the front and was unclosed in a clear acrylic canopy. Most of the actual flying was to be done by an early form of autopilot which handled take off and landings.

The relatively untrained pilot was only there to fire the plane’s weapons which included two different kinds of rockets as well as a 30 mm MK 108 cannon. Once he had taken down his target plane the pilot would eject and the Natter would, in theory, land itself.

This might all seem incredibly advanced for the time, and it was, but the Natter’s actual design was remarkably simple and easy to build. It was designed so that semi-skilled labor (which the Germans had a lot of) could build one in around 1,000 man-hours.

- Top Ten Wild Nazi Weapons of WW2

- The Nazi V-3 Cannon: Could this “Vengeance” Weapon Have Destroyed London?

It was even cheap, using mainly glued and nailed wooden parts with an armor-plated bulkhead. The wings were simply rectangular slabs of wood without the usual ailerons, flaps, or other control devices normal plane wings featured.

The engine was a Walter 109-509 A which was essentially the same engine used in the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet. Using an existing engine helped keep things simple, and controlling the plane was also relatively easy, in theory.

After the initial blast-off, during which 2 Schmidding 109-553 solid-fuel booster rockets were used to give the plane extra oomph, flight controls unlocked and the plane was guided to its target via a 3-axis Patin autopilot which received instructions from the ground via radio. Once the target was in range all the pilot had to do was point and shoot.

A Bold Plan

So far it all sounds very promising. A cheap and easy-to-build rocket interceptor that didn’t need an experienced pilot. So why did the Nazis hold off on greenlighting the Natter for so long?

Well, when Bachem first floated his concept in 1939 the German air force didn’t really feel any great need for such a plane. Early in the war, the German air force had proved itself to be formidable, and maintaining air superiority over Germany hadn’t been a problem. There was no need for a rocket-powered interceptor.

Fast forward to 1944 and things were different. The Allied bombing offensive was taking a massive toll on the German war effort. The traditional methods they had used to intercept allied bombers weren’t working and so radical innovations were needed.

The Germans needed an anti-bomber weapon that could be quickly and easily launched to take out incoming bombers. Surface-to-air missiles quickly showed themselves to be a promising approach to counter the allied bombing offensive.

The only problem with these easily surface-to-air missiles was guiding them. The guidance and homing systems were still in their early days and it quickly became clear that a pilot was still needed to guide them.

Since using Kamikaze pilots like the Japanese wasn’t an option the Natter became appealing. It had the benefit of a missile (vertical launch, rapid acceleration, and interception) but was armed and guided like a conventional plane. Best of both worlds.

Since things were going poorly for the Germans the solution also needed to be quick, easy, and relatively cheap to build. Bachem and his Natter had those bases covered. If he could iron out some of his design wrinkles the Nazis hoped the Natter could be the answer to halting the Allied bombers as they swept across the fatherland.

Was it Ever Going to Work?

The short answer is no. During early testing, it quickly became apparent that Bachem’s mechanical design worked but there were problems. On February 25, 1945, a completed Natter carrying a dummy pilot successfully launched, showing that the complete flight profile was workable. The dummy and main engine were even recovered.

The problem was that was the only thing that worked. Stability issues plagued the aircraft and its guidance system was rudimentary at best. The plane’s performance was also limited by the technology of the time and questions were raised as to whether it was quick and maneuverable enough to be of any use in combat.

Even if these technological/ mechanical problems had been solved there were strategic issues that were much harder to overcome. The problem was that once the Germans erected a Natter site, the US and British air forces’ strike planners could easily route their bombers out of range of the Napper launch site.

Combined with the poor accuracy of the guidance and doubts over whether the Napper was fast enough in the first place the Napper looks less and less like an effective bomber interceptor.

Towards the end of the war, the Germans erected a battery of ten Natters just outside of Stuttgart. The Napper pilots waited on high alert for days but no bombers ever came into range, highlighting the strategic weakness of the Napper.

Not long after the U.S. seventh army overran the Napper installation, the Germans were forced to destroy the prototypes rather than risk their new technology falling into enemy hands. Whether the allies would have had any use for the technology so late in the war is debatable.

Today only two Bachem Natters still exist, one in a museum in Germany, the other in the US The Germans lost the war before the Napper program could be completed so we’ll never know if they would have managed to work out all the kinks given more time. It does seem though that the Natter was largely a bad idea from the start.

But this does not mean the project was a complete disaster. Much of the technology and thinking behind the Natter program went on to inspire later aeronautical developments like advanced surface-to-air missile systems and later attempts at VTOL aircraft.

Top Image: The Bachem Natter was designed to launch vertically and to make things as simple for the pilot as possible. Source: Fulvio Spada / CC BY-SA 2.0.