What happens when a breakdown in ethics collides with a desire to make money quickly? When the molasses disaster struck Boston in 1919, residents witnessed it first-hand. What would you do if a tsunami of sticky molasses swept through your house, destroying everything in its path?

The Great Molasses Disaster, often known as “The Big Day,” was one of the strangest calamities to ever strike Boston, but sadly also one of the most devastating. A 2 million gallon (7.6 million liter) molasses tank ruptured on January 15th, 1919, spilling its contents all over Commercial Street in Boston’s North End.

The Messy Molasses Disaster

The tank, which was near the harbor (a prime position for delivery and collection) was itself obliterated in seconds under the thundering pressure of the escaping liquid. The viscous molasses entirely flooded the surrounding area, which was mostly made up of Irish and Italian immigrant households. Some residents became engulfed in rubble and imprisoned by molasses, putting their lives in jeopardy.

If one thinks of the speed at which molasses moves when poured from a bottle, one thinks of a sticky, slow-moving liquid. Unfortunately, this was not the case on January 15th. Molasses is 1.5 times denser than water, but the force of gravity acting on the liquid resulted in it picking up speed frighteningly quickly.

According to reports, the initial wave of the molasses tsunami hit at a speed of 35 miles per hour (56 kph), crushing everything in its path like a lava flow or a landslide. Tragically, Boston had been hit by a cold front that January, making the liquid thicker and much more dangerous to anybody who was caught in its way.

Emergency services rushed to the scene but there was little to be done against such an onslaught. Firefighters blasting constant streams of saltwater onto the molasses and the surrounding area were eventually able to aid the breakdown of the thick sludge, but when the situation was finally under control they were faced with a terrible sight.

The whole area was in ruin and crushed remains of homes stood mute testament to those killed by the disaster. Some of the bodies of the 21 deceased were not discovered until four months after the catastrophe. Among the dead was a man who died horrifically from asphyxiation after becoming stuck beneath the molasses and unable to breathe.

- The Chinese Famines of 1907 and 1959: Natural Disasters or Man-Made?

- Lake Anjikuni: How Did an Entire Village Disappear?

In the heart of Boston, in Haymarket, a makeshift hospital was built to handle the many injuries. Doctors labored around the clock to clear molasses from people’s airways as the sticky liquid could easily cause them to suffocate.

How Could this Tragedy have Happened?

“Explosion Theory Favored by Expert,” the Boston Evening Globe announced early in the investigation. It’s highly likely that this hypothesis was fueled by the USIA’s (United States Information Agency) report that Italian anarchists sabotaged the tank by blowing it.

And indeed they may have been right. When we take a deeper look at this idea, we can see some data that support its veracity. The tank, which was completed in 1915, produced industrial alcohol from molasses, which was subsequently supplied to weapons companies for use in the production of dynamite and other explosives during WW1.

The city, as well as the bereaved citizens of Boston, were eager to know what had led to this tragic catastrophe. In 1920, 119 separate lawsuits were filed against US Industrial Alcohol, the tank’s owners. The trial itself was inevitably a fiasco, with over 2,000 pages of contradictory testimony from all the lawsuits.

However the reality as to what happened finally emerged, and a shocking lapse in ethical responsibilities was exposed. The tank, it was revealed, exploded due to a multitude of circumstances.

The first step had been to investigate the tank’s construction and testing. And here it was found that the tank was not fit for purpose from the start: the manufacturers did not use the right amount of manganese for a tank of that size.

Faulty Tanks and Faulty Integrity

Manganese was an important component for the tank’s structural integrity as, when used in the right amount, it allowed it to bow slightly when full. However, when the metal of this tank was cooled below 59 degrees Fahrenheit (15 degrees Celsius) it became brittle.

The manufacturers should have accounted for the fact that the tank was in Boston, where temperatures drop dramatically in winter. The weather was a chilly 40 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius) on the day of the molasses disaster, well below the level where the structure was compromised.

- The Secret of Lake Nyos: How Did 1,800 People Die Overnight?

- Mount St. Helens Eruption of 1980 with Photos & Video

Another startling revelation concerned the tank’s health and safety regulations. The tank’s maximum capacity was calibrated to 2.5 million gallons (9.5 million liters). The tank has been filled 29 times in all, and on four of those occasions personnel knowingly overfilled the tank, further stressing the frame.

Ronald Mayville, a structural engineer with the Massachusetts consulting company Simpson, Gumpertz & Heger, launched a further investigation in 2004. Mayville’s investigation revealed that, in additional to the other problems, the tank’s rivets were defective. So, when the tank was overfilled, early cracks occurred around these rivet holes.

The staff at the fuel station were apparently aware of these warning flags. Children from the area were known to come by and fill their cups with the sweet molasses that oozed from the tank’s leaks.

Boston appointed attorney Hugh W. Ogden stressed, “‘The general impression of the erection and maintenance of the tank is that of an urgent job … I believe and find that the high primary stresses, the low factor of safety, and the secondary stresses, in combination, were responsible for the failure of the tank.”

Who Was To Blame?

A verdict on who was responsible took three years, finally arriving in 1923 after the city’s longest court case. The US Industrial Alcohol was found guilty of causing $100 million worth of damages to the city of Boston (in today’s money). They had willfully failed to carry out their civic obligation of keeping the city’s residents safe.

In his closing statement Wilfred Bolster, who was the Chief Judge of Boston Municipal Court in 1923 concluded that “Most of the things I’ve looked at don’t really have so much to do with lack of scientific knowledge so much as a lack of responsibility of the people in charge,” he says. “It’s an ethical issue, rather than understanding the science.”

The great molasses disaster’s most heart-breaking aspect is that it could have been averted. Over a century after the catastrophe, the stench of the sticky liquid still serves as a painful reminder of the 21 individuals who died needlessly.

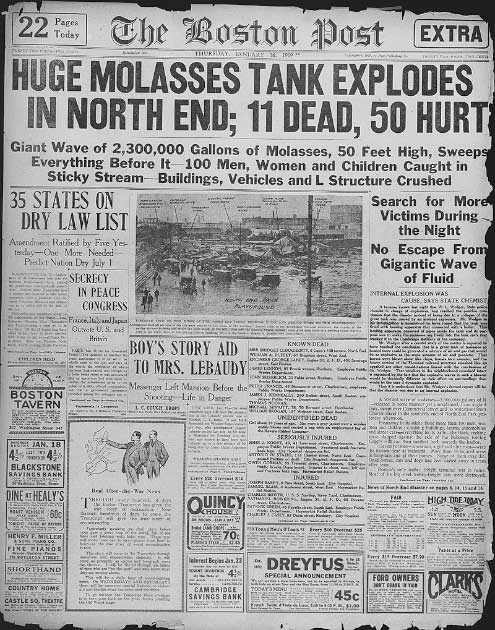

Top Image: The Aftermath: damage caused by the Boston molasses disaster. Source: Boston Public Library / Public Domain.

By Roisin Everard