William Burke and William Hare recognized an opportunity in 1827 and 1828. When the market for fresh cadavers grew at Universities and autopsy schools in Edinburgh, the two enterprising men decided they would fill the need. However, they didn’t do this in the usual way by snatching bodies in graves. Instead, they murdered at least 16 unfortunate souls. The story of the Burke and Hare murders spread like wildfire across the Western Hemisphere and is, undoubtedly, the most famous of its kind.

A Market for Bodies Arises

Edinburgh’s reputation as a venue for advanced medical studies resulted in an influx of students and the rising demand for anatomical studies. Even with the construction of a 200-seat anatomy theatre in 1764, there were more than enough students to fill Dr. Robert Knox’s dissection classes at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in the 1820s. His enterprise was so successful that he offered courses twice a day to some 400 paying students.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, England was subject to the Murder Act, which stipulated that doctors could only use the corpses of executed criminals for medical studies. Under that act, there wasn’t enough supply of cadavers to meet the volume of anatomy classes, as the rate of executions had diminished. Consequently, the price of fresh bodies skyrocketed, which led to the Burke and Hare murders — also known as the West Port murders.

In addition to murder, body snatching became popular. Security guards stood post at several cemeteries to apprehend grave diggers known as ‘resurrection men.’ Another precaution against body thieves was a grill, called a mortsafe, installed over fresh graves. Although William Burke and William Hare chose not to dig up bodies from graves, they had other schemes.

Who Were Burke and Hare?

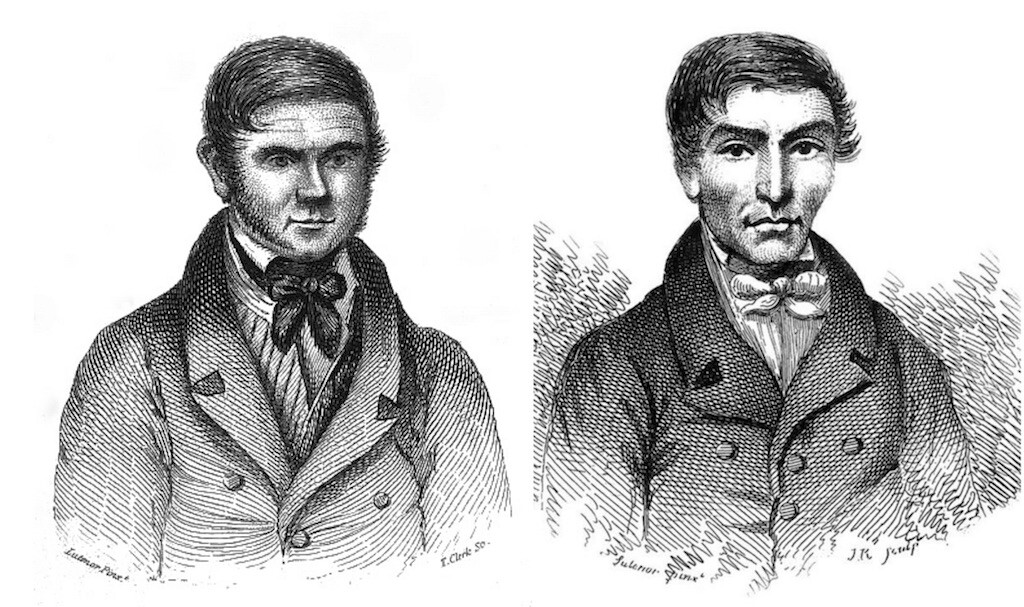

William Burke and William Hare were Irish from the province of Ulster. They had gone to Scotland in 1818 for opportunities in light of the famine in Ireland. They both worked on the Union Canal for some years. Then Burke became a cobbler, and Hare took on odd agricultural jobs.

Bible John: Scotland’s Unsolved Murder Mystery

Burke fell in love with a prostitute named Helen MacDougall, and the two lived together. Around 1826, William Hare shacked up with Margaret, or Maggie, Laird immediately after her husband suddenly died. Maggie and her late husband, Logue, had owned a shabby boarding house in Tanner’s Close, which she and Hare continued to run after Logue’s passing.

Maggie knew Burke because she had also worked on the canal. Thus, when she saw MacDougall and Burke selling their old clothes and shoes in the street, she invited them to rent a room in her boarding house. The two couples initially got along reasonably well in the house and enjoyed tossing back hard liquor and dancing.

The First Death in Tanner’s Close

William Burke and William Hare were, no doubt, pleasantly surprised when one of the other boarders, Donald, became ill and died while he was staying with them. The dead man owed back rent that he failed to pay before he died. Aware that anatomists paid well for cadavers, Burke and Hare stole the corpse from its coffin before internment. They replaced Donald with bags of bark and sold his lifeless body to Dr. Knox for a little more than seven pounds — a sizeable amount of cash at the time.

The financial rewards led Burke and Hare to start a business of suffocating lodgers in Laird’s house to turn them into saleable corpses. For their first fresh victim, either a woman named Abigail Simpson or an old man named Joseph, they charged Dr. Knox 10 pounds, which became their standard fee.

According to author Douglas Skelton, Hare took five pounds, Burke got one pound, and Laird received a pound as the owner of the boarding house. Even Helen appears to have been complicit in some of the murders. However, after exhausting the supply of bodies from house guests, the couples set their sights higher.

Open Season in the Taverns

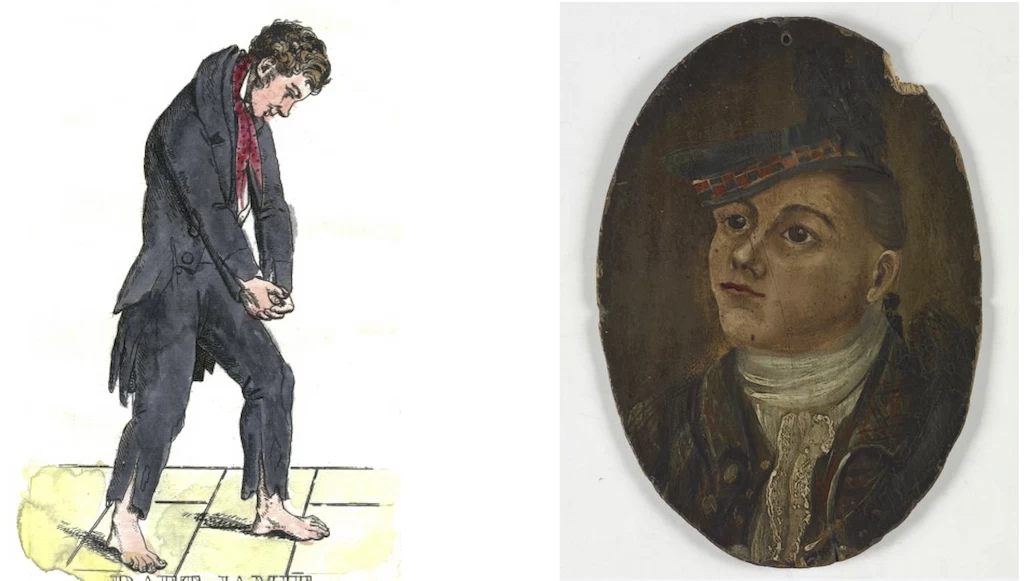

Edinburgh’s taverns proved to be a prosperous hunting ground. The conniving killers charmed their victims with liquor and laughs at the bar. Then they coerced them home, murdered them, and dispatched the corpses to Dr. Knox. The majority of their victims were drifters and transients. However, William Burke and William Hare were becoming bolder and more careless. At least two of their victims had been well-known locals from the area. Mary Paterson was a famously beautiful prostitute. Jamie Wilson (Daft Jamie) was an 18-year-old boy with mental retardation and a foot deformity. The neighborhood of Old Town was particularly fond of Jamie and even looked out for him.

Margaret Laird lured Daft Jamie to her home and handed him over to Burke and Hare. They got him drunk and smothered him. However, the locals quickly noticed Jamie missing, and they worried that something bad had happened to him. Word of his absence spread quickly. Undeterred, Dr. Knox removed Jamie’s head and feet — the parts that could identify the boy — before Knox sent the corpse out for study.

The Last Straw in the Straw

Burke and MacDougall had moved out of Tanner’s Close into their own place not far away. They shared the space with another couple, the Grays. The last murder, the one that foiled Burke and Hare’s operation, was that of Margaret Docherty. It happened when Burke found the Irish woman begging in the tavern. He lured her back to his place under the pretenses that he was somehow related to her. Before killing Margaret Docherty, Burke told the Grays that Docherty needed a place to stay and convinced them to go to Tanner’s Close for the night.

When the Grays returned to Burke’s apartment the next morning, the lodgers discovered Docherty’s body stuffed in the straw mattress and reported it to the police. While they were making their statement, the killers placed Docherty’s corpse in a trunk and delivered it to Dr. Knox. The police who followed up on the matter found blood in the straw of the bed at Burke’s place. Docherty’s body awaited the police in Dr. Knox’s morgue. Subsequently, they arrested Burke, Hare, MacDougall, and Laird.

Burke and Hare Trials

Prosecutors had lots of circumstantial evidence but no witness testimony, so they made a deal with William Hare. He would serve as a witness for the Crown and testify against William Burke in exchange for immunity. While Margaret Laird also received protection, Hare testified that Burke was responsible for all the murders. Helen MacDougall was tried and received a verdict of ‘not proven.’

Burke went to trial in December of 1828 for the murder of Margaret Docherty, James Wilson, and Mary Paterson. This did not account for all 16 murders. However, it was enough to secure an execution. At the trial, Dr. Knox claimed that William Burke and William Hare told him they had bought unclaimed corpses of deceased individuals from boarding houses. However, many people believed he knew what was going on and simply turned a blind eye.

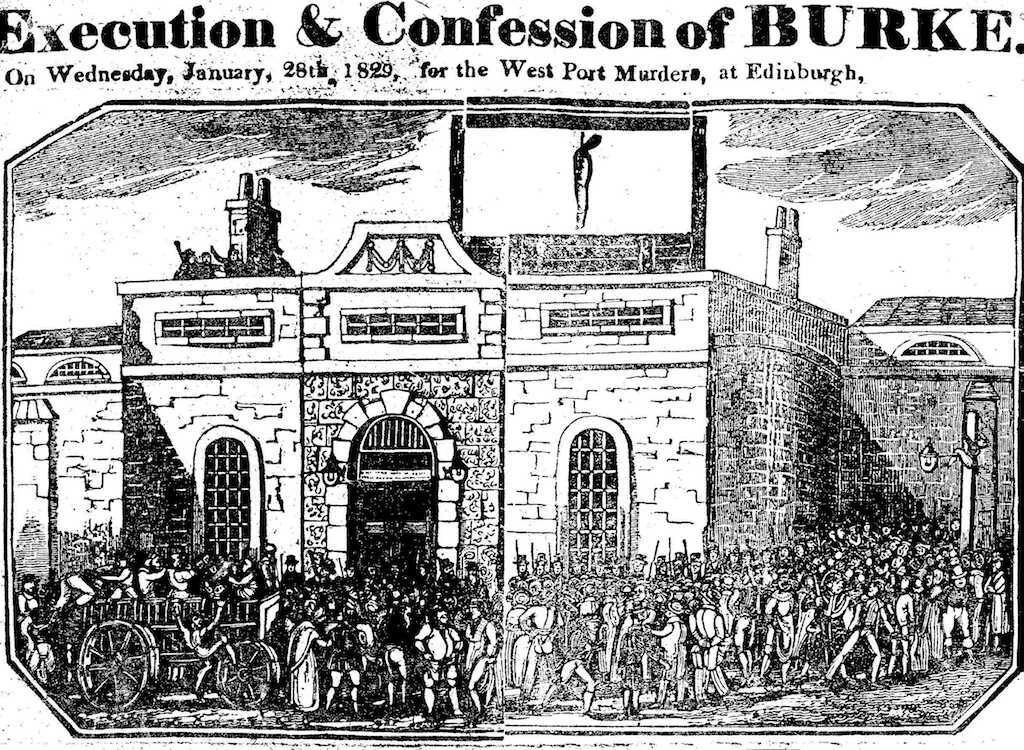

The jury found Burke guilty, but it wasn’t unanimous. Two jurors were uncertain about his sole responsibility for all three murders. Nonetheless, William Burke hanged on January 28, 1829, at a crowded public event that seemed more like a sporting event.

The Anatomical Aftermath of Burke’s Trial

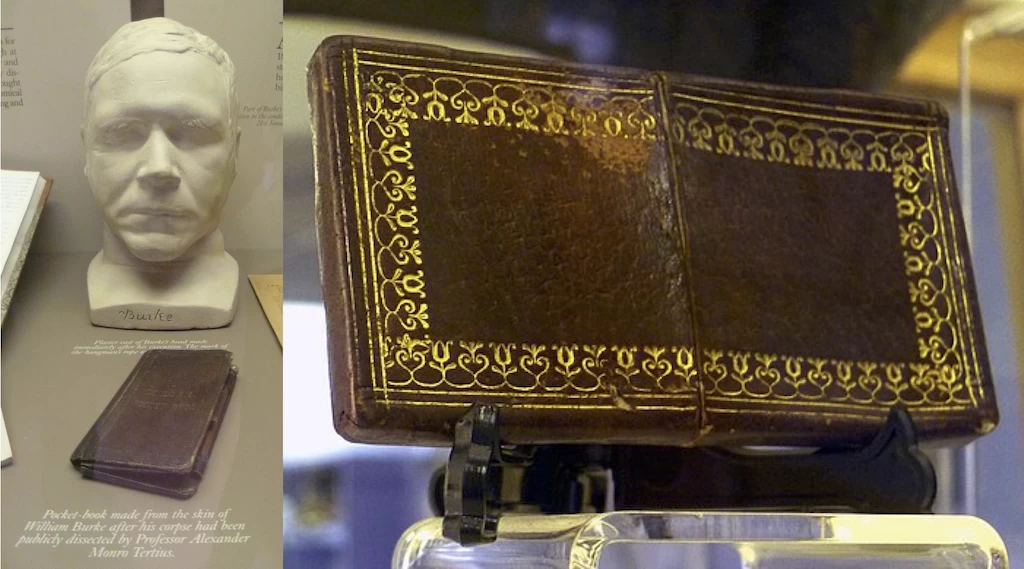

Ironically but not surprisingly, the judge sent Burke’s body for public dissection. The brutal and open nature of this practice served as a deterrent for anyone thinking of committing murder. Supposedly, a large auditorium filled up with medical students who watched an anatomist cut Burke to pieces. Subsequently, Burke’s skeleton went to the Anatomical Museum of the Edinburgh University medical school, where students and staff can view them today. Additionally, a death mask and a book bound in Burke’s skin lies in the Surgeons’ Hall Museum.

As was the tradition with murderers, Burke did not receive any funerary rites or a proper burial. Additionally, according to Christian doctrine, an anatomized body would not rise from the grave on Judgement Day.

Hare was released from prison in February 1829 and, after escaping a wrathful mob, escaped to England. Whatever became of him is unknown. Although Dr. Knox was cleared of having any knowledge of where the bodies came from, the public wanted justice for his involvement. They attacked his house and the anatomy theater, and the professional community shunned him. With few students left in his school, he left Edinburgh in 1842 to seek work as an anatomist in London.

A New Bill Increases the Supply of Cadavers

After the Burke and Hare murders, a duo of copycat killers, Bishop and Williams, surfaced in London. They hanged in December 1831. However, their crimes highlighted the need to change the Murder Act. Therefore, in August of 1832, parliament passed the Anatomy Act, which allowed medical students and teachers to use donated corpses.

England saw an increase in the supply of cadavers and fewer murders in the name of science and medicine. However, in the U.S. during the late 1880s, another serial murderer got to work. H.H. Holmes confessed to 27 murders. Many people believe his victims may have numbered in the hundreds. Holmes also sold many of his victim’s corpses and skeletons to medical organizations for money.

Burke and Hare Live on in Mainstream Media

The story of such unconscionable serial killers motivated by financial gain captured the public’s imagination. Not only would the term “burking” (a murder by suffocation, which would leave the body in pristine condition for sale) derive from Burke and Hare’s murders. A plethora of artwork, movies, plays, blogs, and literature stem from the famous duo.

Fortunately, anatomists and universities today get most of their cadavers from unclaimed individuals and those who donated their bodies to science. But during the 19th century, the market for humans led to many untimely deaths and made the two Irishmen in Edinburgh a fortune.

References:

McCracken-Flesher, Caroline. The Doctor Dissected: A Cultural Autopsy of the Burke and Hare Murders. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Rosner, Lisa. The Anatomy Murders: Being the True and Spectacular History of Edinburgh’s Notorious Burke and Hare, and the Man of Science Who Abetted Them in the Commission of Their Most Heinous Crimes. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

Unknown. “Burke’s Confession.” Burke’s Confession, Fresno State University,

Skelton, Douglas. Deadlier than the Male: Scotland’s Most Wicked Women. Black and White, 2003.

Tarlow, Sarah. “Murder and the Law, 1752–1832.” Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse [Internet]., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 18 May 2018.