The hillside of Capodimonte in Naples, Italy, is home to the largest Christian subterranean necropolis in Southern Italy. Named after Saint Januarius (Gennaro in Italian) who was once buried at the site, the Catacombs of San Gennaro is a cemetery complex containing roughly 3,000 tombs. The oldest vestibule dates to the second century CE. With its amazing works of ancient art and some of the oldest Christian frescos and mosaics, this sacred site of burials and worship is one of the most incredible archaeological discoveries in the region.

The upper level of the Catacombs of San Gennaro. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

It appears that the area started as a pagan site of worship and burial. Later, as Christianity spread, Christians began expanding and using the complex.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Selene”]In the oldest part of the cemetery complex, pagan art and culture is mixed with that of early Christianity. Apollo and (maybe) Diana are magically transformed into Adam and Eve, Bacchus lends his emblems to Christ and the good pastor starts to appear; as well, the deer, the lamb, the peacock, the cross. Angels and gods living together.[/blockquote]

Construction of the Catacombs

Funerary rituals in ancient Italy were an important matter. According to the laws of that time, it was illegal to bury the dead near the living. Thus, they placed the tombs a good distance away from the city walls but close enough that they could visit the deceased regularly.

Fortunately, the soft volcanic tufo (tuff) stone of the Capodimonte mountain made it ideal for the construction of the catacombs. Additionally, once the stone dried in the open air, it became stable and solid. This is evidenced in the survival of the Catacombs of San Gennaro for nearly 2,000 years. Over time, the city of Naples has grown significantly and now embraces the 60,300 square feet of subterranean tombs close to its heart.

Types of Tombs and Burials

The tombs reveal how much wealth and status the deceased had. For those with little money, modest nooks in the walls or floors served as small crypts. The wealthy had larger crypts typically with arches (arcosolia) or domes bearing frescos or mosaics. Just below the domes lie the tombs that once encased the body. Usually, the decorations served as remembrances of the individual and contained his or her image. At one time, marble slabs sealed the remains in each tomb. Additionally, the catacombs contained roughly 500 sarcophagi or stone coffins.

Lower Level of the San Gennaro Catacombs

The San Gennaro catacombs consist of the lower vestibule and the upper vestibule. As noted, the lower vestibule is the earliest section. Initially, it may have started as the pagan tomb of a wealthy family c. 200 CE. Around 400 CE, Saint Agrippinus was buried at the site. As Christians of the time believed that it was a blessing to be close to a saint, the demand for tombs near Agrippinus increased and, subsequently, the first phase of expansion took place.

Lower Catacombs of San Gennaro. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

A basilica carved out of the tuff rock was dedicated to St. Agrippinus. It contains a stone Bishop’s chair (behind the altar) and an altar with a hole in the center where worshippers could see and touch St. Agrippinus’ tomb.

Altar of St. Agrippinus. This basilica is still in use today. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

In the eighth century, Bishop Paul II took refuge in the first level of the site during religious tensions. He built the baptism pool that still exists just in front of the basilica.

Bishop Paul II built this baptismal font in the eighth century CE. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

During the Great Persecution (of Christians), San Gennaro became a martyr in 305 CE after he was beheaded in Pozzuoli for professing his faith in Christianity. However, his remains stayed in Agro Marciano in Pozzuoli until Bishop John I moved them to the lower level catacombs in the early fifth century. The catacombs became synonymous with the famous patron saint and took the name Catacombs of San Gennaro. Subsequently, another phase of expansion occurred and Christians, once again, increased their pilgrimages to the site.

The Upper Level

After San Gennaro’s placement into a lower level cubicle, an expansion of the upper level was necessary for the accommodation of the increase in visitors to this now highly sacred religious site. Not only did Christians want to pay homage to San Gennaro, but many of them also wanted a tomb near his resting place.

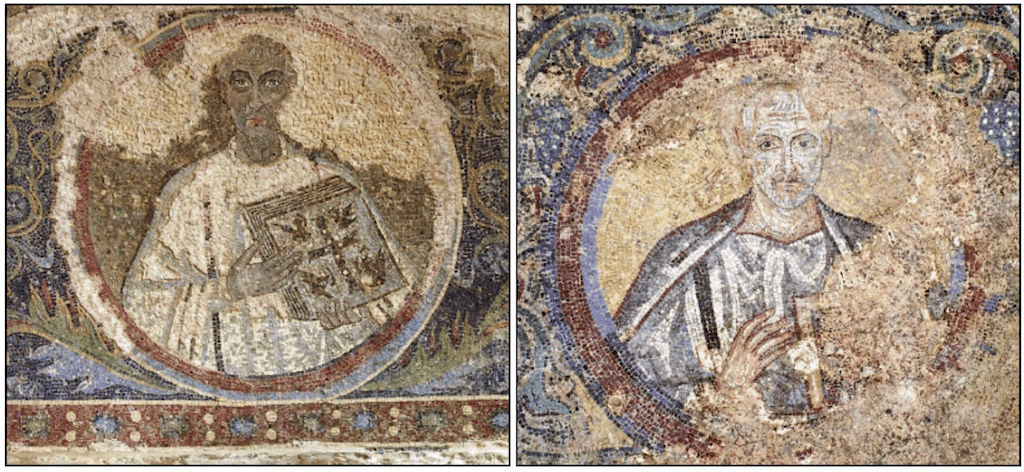

For this reason, construction of additional upper-level tombs started along with the addition of another basilica and the Crypt of the Bishops above San Gennaro’s cubicle. The bishops’ crypt contained some of the first bishops of Naples in addition to their names and amazing mosaics.

Mosaics in the Crypt of the Bishops. Quodvultdeus the North African bishop (L), Bishop John I (R). Photos: PCAS Archive.

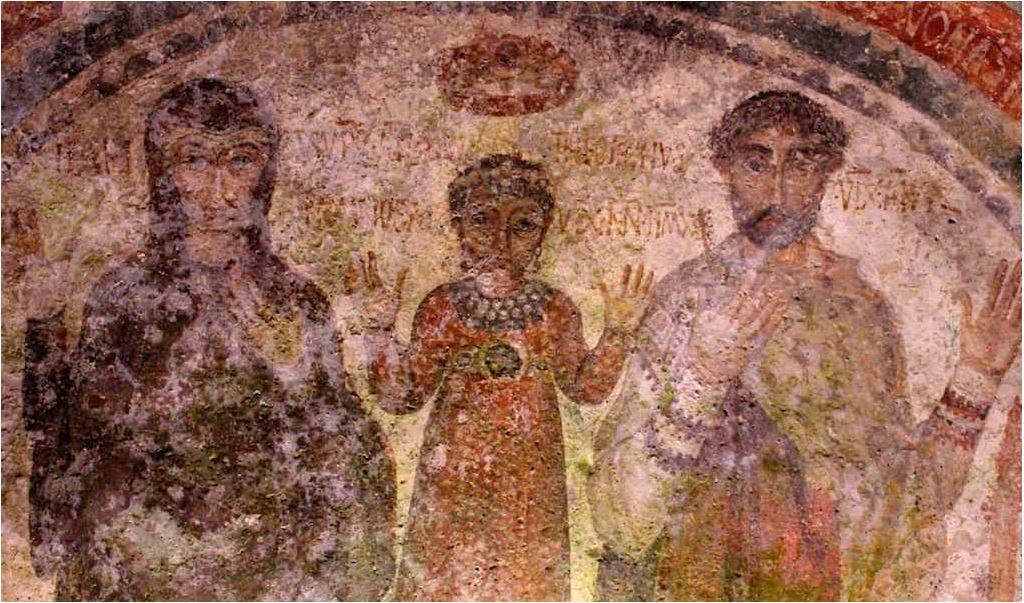

Fresco of Ilaritas, Nonnosa, and Theotecnus

They say a picture is worth a thousand words, and this exceptional fresco of a woman, a female child, and a man certainly tells a lot. As this arcosolium contains the names of the family members and their ages of death, this is one of the most important artworks in the San Gennaro catacombs.

The noteworthy fresco of Theotecnus, Ilaritas, and Nonnosa at the Catacombs of San Gennaro. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

The colorful image lies over the burial tomb of a wealthy family in the upper vestibule of the catacomb. Its location tells us that the family died between the second or third century AD and the sixth century AD.

According to the writings on the fresco, the mother’s name was Ilaritas. The fresco states that she died when she was 45. Nonnosa, Ilaritas’ daughter, died at the early age of two years and 10 months. Finally, Theotecnus was Nonnosa’s father, and he died when he was 65 years old. It is interesting that the fresco does not mention the year of death: only their ages.

There is evidence indicating that the fresco has been reworked at least three times in the past. Researchers believe the original layer only displayed Nonnosa. When her father passed away, it was covered by a new fresco showing Nonnosa with her father. Finally, when Ilaritas passed away, a final fresco depicted all three of them.

Symbolism in the Family Fresco

In the fresco, Nonnosa is wearing a red dress and both of her hands are up with palms out. In the ancient world (and even now), this gesture is a visual representation of praise and prayer in a religious context. Although she is apparently wearing a wreath around her head, a crown floats above her. This probably symbolizes her state of holiness or righteousness and the everlasting life that she has earned through her moral purity. A pearl necklace adorns her neck, and additional jewelry dangles from her dress.

Theotecnus is shown with a short beard. His tunic appears to be designed with jumping antelopes. Both Ilaritas and Theotecnus are also holding one hand up and out in a praise position, while the opposite hand faces toward the body. Additionally, Ilaritas wears dark clothing signifying that she is mourning. In this case, the family’s clothing and adornments clearly indicate their wealth.

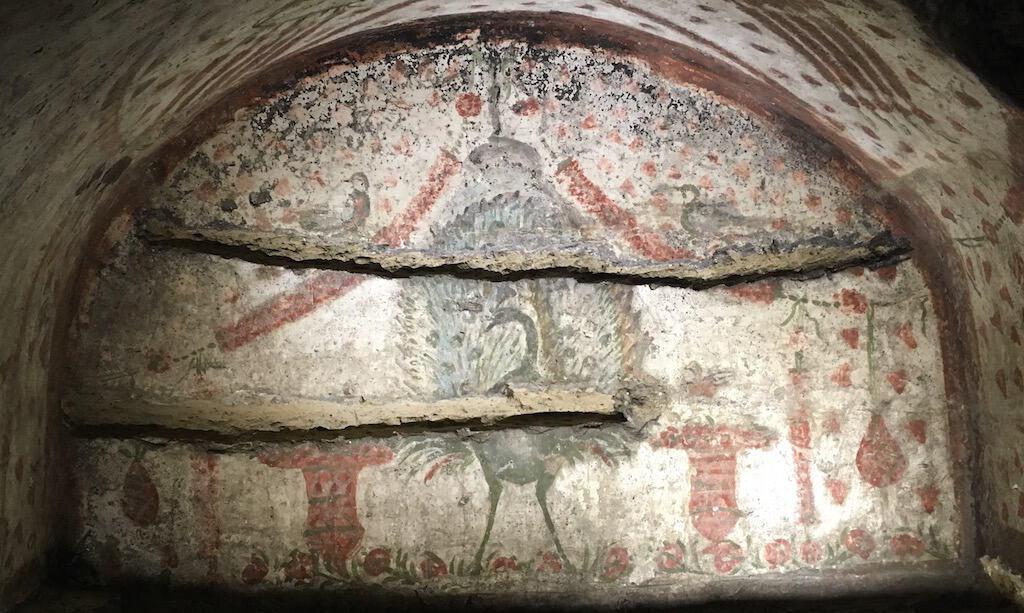

The Peacock

While most of the painted arcosolia depict images of the person interred below, the subject of this fourth-century painting is a peacock. In the image, two birds sit above the peacock on his left and right side. What appears to be fountains are on both sides next to him. Another small bird is visible on the right-hand fountain. Additionally, the peacock is standing on a bed of roses, and rose petals dot the backdrop of the painting. These symbolize happiness in the afterlife.

The peacock arcosolium contains important religious iconography. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

“In Christian iconography the peacock symbolizes the immortality of the soul which enjoys eternal life. In the past it symbolized the awakening of life in the spring because it loses and renews the feathers, while the “wheel” of his tail, became picture of a starry sky” (Zambella et al. 2013).

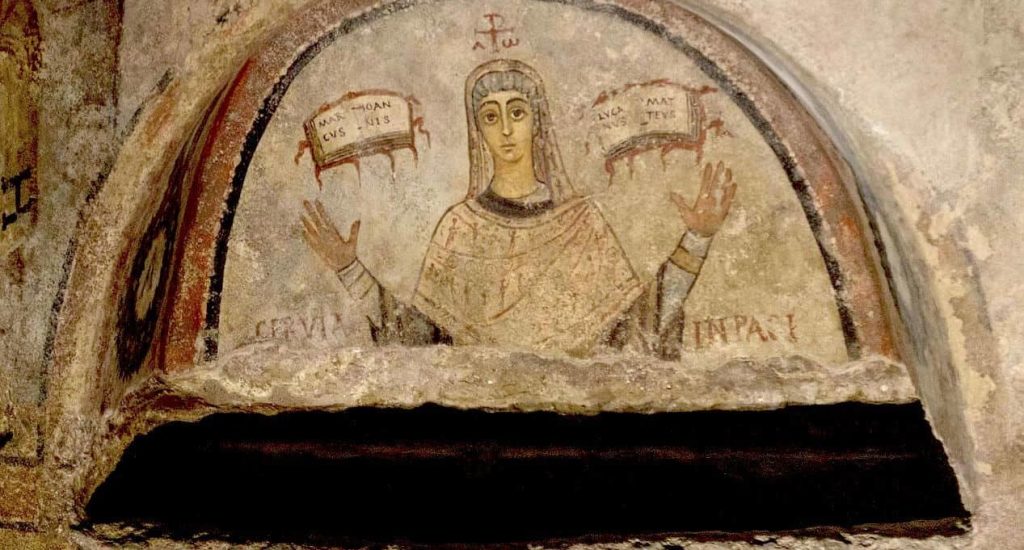

Arcosolia of Cerula and Bitalia

Cerula and Bitalia are two women who have become quite controversial in the international arena. Both of their arcosolia have frescos that reveal each woman in the open arm prayer position. Flaming books, probably gospels, float above the hands near their heads. Experts believe this symbology was reserved for bishops in the church and that this may solve an age-old controversy about whether or not women held prominent positions in early Christianity. In Cerula’s fifth-century fresco, shown below, she also has the Chi-Rho symbol, representational of Christ, above her head.

According to an article in The Telegraph, in the late fifth century, Pope Gelasius wrote a letter of disapproval to the bishops of South Italy regarding women who were ministering at Christian altars.

Cerula may have been a minister of the early Christian faith. Photo: CC4.0 Dominik Matus.

Where Did All the People Go?

Saint Januarius remained in his cubicle at the Catacombs of San Gennaro until in 831 when a Lombard prince stole his remains and took them to Benevento. They were eventually returned to Naples in 1497 and now lie in the Naples Cathedral.

In the 13th-18th centuries, robbers looted the tombs. As a result, caretakers emptied the tombs and transferred most of the bodies to the Fontanelle Cemetery, not far from the San Gennaro’s catacombs.

References:

Bisconti, Fabrizio, and Fabrizio Bisconti. “Napoli. Catacombe Di S. Gennaro. Cripta Dei Vescovi. Restauri Ultimi, in Rivista Di Archeologia Cristiana 91, 2015, Pp. 7-34.”

Catacombs of Naples

Selene. “A Special Day in the Catacombs of Naples.” Napoli Underground.

Zambella, C & Ciocia, C & Loffredo, Filomena & Pugliese, Mariagabriella & Quarto, Maria & Roca, V & Rita Pinto, M. (2013). “Environmental Monitoring of the St. Gennaro and St. Gaudioso catacombs in Naples.”

Updated July 11, 2019.