In 1890, the coal mining town of Centralia, Pennsylvania, was home to more than 2800 people. Just like in any other town, rows of houses lined the streets, townsfolk had barbecues in their backyards, and everyone put up Christmas decorations during December. In 1962, the Centralia mine fire propelled the quiet borough into the spotlight overnight. The routine controlled burn went below ground catching the natural reserves of anthracite coal on fire under the community. It never stopped. Conditions became so dangerous, people left voluntarily or the government coerced them to leave. Fifty years later, the ground still burns, and the town, if you can call it that, is no more than a ghostly condemned zone.

The Centralia fire has been emitting heat and noxious smoke since 1962. CC2.0 Aaron Muderick

The Early Days of the Mining Town

Centralia was founded in 1866 in Pennsylvania’s Columbia County between routes 61 and 42 by mining engineer Alexander Rea. With an abundance of anthracite coal under the ground worth billions of dollars, the town became prosperous. The mines supported a population of around 1500 people, and the number continued to grow until about the early 20th century.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Centralia PA”]At that time, the vibrant borough had five hotels, 27 saloons, seven churches, two theaters, one bank, and a post office, as well as 14 general and grocery stores.[/blockquote]

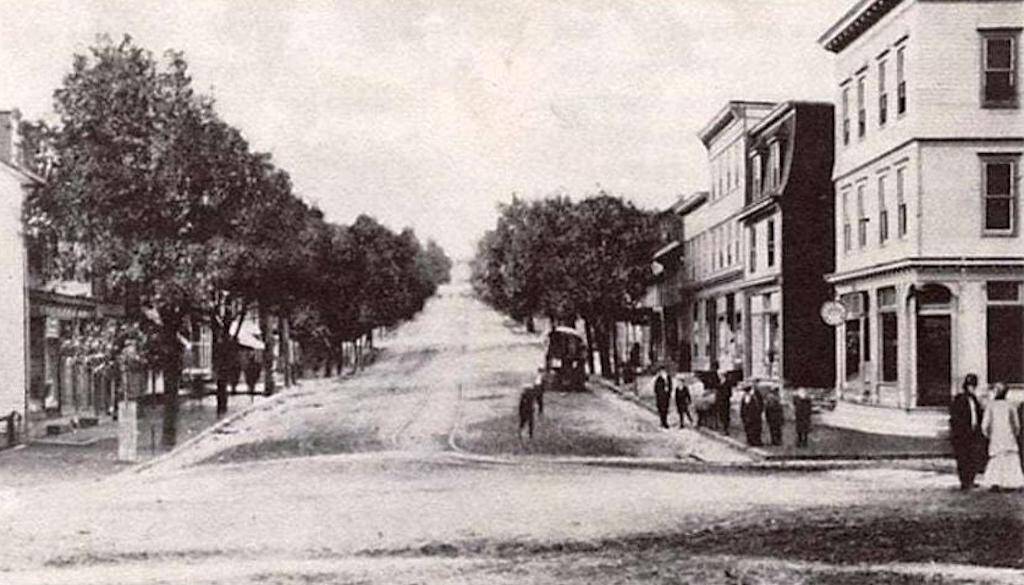

Before the Centralia mine fire, Locust Avenue, 1915. CC2.0 dfirecop.

The town’s heyday came in the early 1900s when it reached a population boom of around 2800 residents. In the 1950s, it was still a small, close-knit community of schools, churches, neighborhoods, and hardworking adults who mined coal or worked the stores that supported the town.

The Day the Coal Fire Started

On May 25, 1962, the quaint mining town changed forever. The town council wanted to get ready for their big Memorial Day celebration. However, the illegal garbage dump left an unsightly mess that would interfere with their plans. So, they discussed their options and decided to burn it.

The local firefighters lit the blaze and burned out the trash. Then at the end of the day, they put out all the visible flames that they could see above the surface. What nobody knew right away, however, was that an old mining seam with flammable coal and coal dust beneath the town had caught on fire.

Flames continued to crop up around the initial burning site over the next few days. Several efforts were made to put out the fire, but it continued to spread below ground. The network of old mining tunnels stoked the fires with a steady supply of oxygen, and the rich anthracite coal deposits offered it plenty of burnable fuel. For weeks, random fires would spring up as the coals burned. Even without visible fire, the stench of burning coal and smoke permeated the town.

Dangers for Townsfolk

For years, the authorities tried to put a stop to the fires, but their attempts were futile. They tried pumping water into the shafts. This only left the town at risk of dangerous steam explosions. Additionally, they dumped in clay and slurry. Those failed too. For almost twenty years, the people of Centralia coexisted with the fire. However, this less than cozy arrangement was unsustainable as conditions became ever more threatening. In 1969, three families had to leave their homes due to the presence of toxic fumes.

In November 1979, John Coddington, who owned a gas station, noticed steam rising from the lot next to his station. He had four underground gas tanks holding a total of 9000 gallons of gasoline. Thus, John became concerned. Then in early December, he saw steam coming from his basement floor which was warm to the touch and measured 136 degrees Fahrenheit. Officials began monitoring the temperature of the gas. The heat was steadily rising. As a result, the Pennsylvania Police fire marshall ordered the shut down of the station. Coddington had to pump all the gas tanks and fill them with water to prevent an explosion. In 1981, Coddington’s Gas and Service Station was demolished.

The Final Straw

Also in 1981, on Valentine’s Day, a steaming 150-foot fissure that once served as a mine shaft opened up under a 12-year old boy, Todd Domboski. He fell in about 6 feet but grabbed onto a tree root. His cousin, Eric Wolfgang heard Todd’s screams and ran over to pull him out. Later, officials measured the temperature inside the hole at 350 degrees. Todd was uninjured, but it was a wake-up call for the people in the town.

A few weeks later, an elderly man was rushed to the hospital for carbon monoxide poisoning after he passed out – a direct result of the underground fire. Officials indicated that had it been only minutes later, the man probably would not have survived.

Todd Domboski fell into this steaming hole caused by the mine fire. CC2.0 dfirecop.

The Centralia coal fire brought not only smoke, odors, and dangerous sinkholes, but also many harmful and carcinogenic chemicals into the air. Specifically, “Direct hazards to humans and the environment posed by coal fires include emissions of pollutants, such as CO, CO2, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, toxic organic compounds, and potentially toxic trace elements, such as arsenic, Hg, and selenium” (USGS).

From Coal Town to Ghost Town

It was too dangerous for the townsfolk to stay. Divergent factions formed in the community. Some folks wanted the government to buy them out so that they could make a fresh start someplace else. Others wanted to attempt to maintain their community. Additionally, a number of citizens suspected a government and big-business conspiracy that would remove everyone from the town to free up the coal reserves to large mining companies. The once tight-knit community was turning against each other.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Stephen R. Couch”]The outcome of these differences was a two-year period of intense intracommunity conflict. Town meetings ended in shouting or fistfights. Telephone threats were made, car tires slashed, and at least one fire-bombing occurred. Many neighbors – and even some family members – no longer spoke to one another.[/blockquote]

In 1983, the government allocated $42 million for the Centralia Mine Fire Acquisition Relocation Project – a voluntary buyout program for land and business owners. Over the next several years, almost everyone was bought out of their properties at the fair market value. (Couch).

By 1991 almost everyone had moved away. Once they left, their homes were leveled, leaving only empty streets behind. The small minority of 58 people refused to leave the only place they had ever known and loved. They felt betrayed and scorned those who left.

In 1992, Pennsylvania ordered the remaining people out but gave them one last chance for the buyout program. Then they issued an Eminent Domain and took legal, but not physical, possession of the last houses. This meant that the state now owned all the properties left in the town. The remainders filed a lawsuit that took 20 years to resolve. Eight residents remained in the city until they either chose to move or passed away. However, those people no longer owned their properties; the government did. Today, only a few folks are all that’s left in the Centralia ghost town.

Destination: Graffiti Highway

The burning town in Pennsylvania has become something of an interesting tourist attraction. Many people who visit the abandoned city say that it has the feel of a post-apocalyptic movie or a war zone. Concrete remnants are all that remain of the streets that once contained rows of houses. Twisted and bent stairs, sidewalks, and the Old Hwy 61 bear the large cracks and charring from the fiery heat below the city.

The underground coal fire, evident by rising steam, caused Old Hwy 61 to swell and crack. CC2.0 t3hWIT.

A few homes, one church, and the graveyards remain. The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church even holds weekly services. Sometimes smoke rises out of the ground in one old cemetery, which is very close to where the fire started.

The Graffiti Highway is probably the most famous remaining attraction in the old town. Once, this was part of Route 61. But the enormous asphalt ruptures from the fire beneath the ground caused the state to reroute the highway in 1994. Graffiti now covers the three-quarter-mile roadway which lies in disrepair and abandonment. Like most graffiti around the world, some messages are artistic and uplifting while others are vulgar and filled with expletives.

The Graffiti Highway is a famous landmark. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

What Lies Ahead

The burning Pennsylvania ghost town has managed to live on in movies, TV, radio, and print and online sources. Several documentaries have aired. In 1982, Martin Sheen narrated the PBS program, “Centralia Fire.” Chris Perkel and Georgie Roland put out “The Town That Was” in 2007. Recently in 2017, Allyson Kircher released “Centralia: Pennsylvania’s Lost Town.” All the documentaries tell the poignant and controversial story from the beginning with interviews and historic footage and photos. Additionally, the French-Canadian motion film “Silent Hill” received its inspiration for its horror story from the burning ghost town.

For a hundred years, mining families made the small mining borough their home. Then one fateful decision erased nearly everything they built. Most of those people painfully relocated and started their lives all over again, while a few stayed in the lonely town where they quietly passed away or still live. Once the last few folks move on, the only thing that will remain is the fire which will burn on and on for hundreds, if not thousands, of years into the future.

References:

Calderone, Julia. “This Town Has Been Burning for 50 Years.” Business Insider. July 13, 2015.

Centralia PA. “History of Centralia PA Before 1962.” July 11, 2016.

Levine, Jeffrey R., and Jane R. Eggleston “The Anthracite Basins of Eastern Pennsylvania.” USGS.gov, n.d.

Morton, Mary Caperton. “Hot as Hell: Firefighting Foam Heats up Coal Fire Debate in Centralia, Pa.” EARTH Magazine, March 4, 2014.

Couch, Stephen R. “3 Environmental Contamination, Community Transformation, and the Centralia Mine Fire.” United Nations University, n.d.