Much of what we consider to be inviolable in our society stems from human invention. From social codes of conduct to responsibilities to each other, from human rights to individual freedoms and liberty, the patchwork of human interactions are the result of millennia of development and experimentation.

But of course such a time existed before such social arrangements were put into place, much less codified. Someone, somewhere had to start with a blank slate (perhaps quite literally) on which to make the first attempts at writing down a rule book for our social interactions.

What might this earliest set of rules have looked like? What might it tell us about the society that created them, and through the lens of their truth our own society. In this we are extraordinarily lucky in that much of this earliest law survives to this day, and we still have a record of the Code of Ur-Nammu.

An Ancient Law

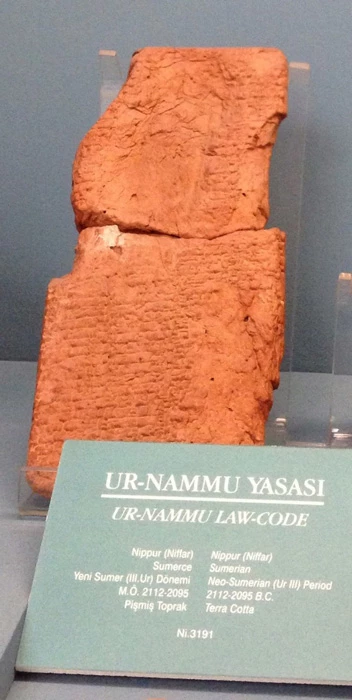

The Code of Ur-Nammu, written between 2100-2050 BC, is the world’s earliest extant legal code. It was written centuries before the more famous Code of Hammurabi was penned by the Babylonian monarch Hammurabi between 1795-1750 BC.

This first law comes from one of the oldest civilizations in the world, Sumer. The law was written either by the Sumerian king Ur-Nammu 2047-2030 BC, or his son Shulgi of Ur. Other, even older laws exist, such as the ancient Code of Urukagina from some two hundred years earlier, but Ur-Nammu created the first combined and balanced legal system.

Although the Ur-Nammu Code is imperfect, enough of it has been survived to allow academics to comprehend the king’s idea of law and order in his territories. Ur-Nammu portrayed himself as the father of his people, encouraging his followers to consider themselves as one family, and his laws as the rules of a home.

In this approach we see harsh discipline but also leniency. Except for fatal acts, punishments were in the form of fines, similar to how a child could be denied a favorite pastime or toy for misbehaving.

- Uruk, the First Great City: A Leap Forward for Humankind?

- The Epic of Gilgamesh: Mankind’s First Story?

Samuel Kramer deciphered the first copy of the code, discovered in two shards in Nippur in what is now Iraq, in 1952. The Istanbul Archaeological Museums house these relics. Only the prologue and five of the laws were apparent due to its incomplete preservation.

The World of Ur-Nammu

The region of Mesopotamia at this time had been long dominated by the Akkadian Empire, founded by Sargon of Akkad 2334-2279 BC. However around 2083 BC the Sargonid Dynasty, weakened by drought and hunger, was overthrown by an invasion by the West Asian Gutians.

The Gutians (from modern-day Iran) then portrayed themselves as the Sargonids’ heirs, but according to Sumerian chronicles they lacked the administrative skills and religious cohesion that had allowed Sargon and his predecessors to rule so efficiently. Simply put, they lacked the bureaucratic apparatus to rule the lands they had conquered.

Even the Sargonids had not been able to maintain a peaceful empire. Though they had maintained order for generations, this was through military dominance and this led to the need to constantly fight to maintain order. The citizens never accepted their Sargonid rulers.

Clearly some form of agreement between the ruling class and the populace was needed. If the kings could put into place a legal code which (nominally at least) applied to all, then the population would be instilled with a sense of order and fairness in treatment, which might make them more amenable to their social position.

Not Too Different from the Modern Day

The laws are unquestionably more brutal than those preferred by the modern world, with summary execution for the most serious crimes such as murder, robbery and rape a standard inclusion. However there are fines for the “lesser” crimes involving slaves which allow historians to understand the value which the Sumerians placed on a human life, and the relative importance of the enslaved versus free citizens.

There were also standard payments for physical injury, but also how much a man must pay in a divorce (one mina of silver for your first wife, half a mina for all subsequent divorces). Some other, more unusual punishments were also outlined, such as having your female slave’s mouth filled with salt if she compares herself favorably to you.

The laws seem to have been made with extreme care and to present a sense of balance in the treatment of crimes according to their severity. It is hard to tell if the comparative severity of the crimes as outlined in the code was generally agreed upon at the time, but the fact of the successful adoption of these laws suggests that they must have seemed reasonable.

However, tellingly there is no mention of error in the sentencing in these laws, nor room for accusations which were later proven to be false aside from fines. The specifics of reasonable doubt and the army of lawyers looking to exploit the legal system seems to have come much later.

On Divine Authority

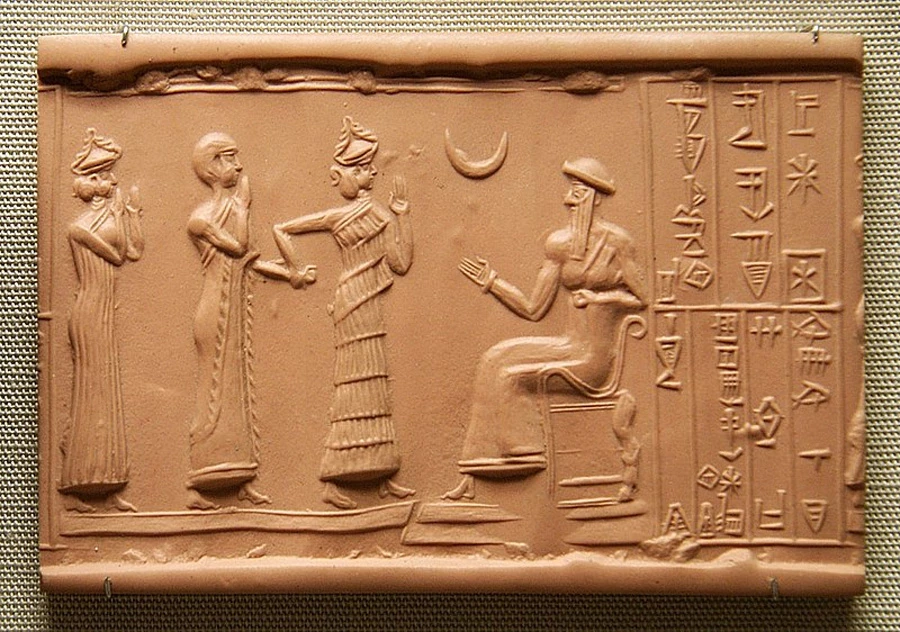

While the legal system in the code seems reasonable, Ur-Nammu would have been aware of the dangers of introducing such a set of rules. Therefore, recognizing the potential of religious beliefs to influence personal behavior, he presented his laws as having come from the gods.

He appears to have made certain that people understood that the king was just the administrator, not the inventor, of the code, and that breaking the law was a form of rebellion against the divine will. The code was then widely disseminated throughout the reign of Shulgi, who, as previously said, may have even been the author.

There was no need for a public exhibition of the rules, however, because the inhabitants of Ur-Nammu and Shulgi shared a common set of beliefs and customs. In this way it does seem that the laws were designed to encourage correct behavior within already established bounds.

The rules also detailed sanctions for offenses that, under the later Hammurabi Code, would be dealt with significantly harsher. Was the Sumerian civilization able to achieve a period of peaceful prosperity which the later Babylonians could not achieve?

Aside from the basic conditional formula (if-this-then-that), the one thing the two codes had in common was the assertion that they had been given to them by the gods. This characteristic was obviously a powerful incentive to obey, and would subsequently appear in later law codes such as that of the Assyrians, and the Hebrew Bible’s Mosaic Law.

Just as Ur-Nammu attributed Shamash’s (the Sumerian father god) code to him, Moses is said to have received his from the Hebrew god Yahweh. This policy of attributing laws to divine instruction is a risky business however: while it gives the codifiers immense authority, any flaws in judgement or anachronistic rules may expose the fakery behind the composition.

However in this Ur-Nammu appears to have been wise. His laws were careful to follow a recognized system which seems to have fitted with the expectations of the populace. By not stepping outside these tacit agreements for his own benefits, this represents a social contract between a king and his people, a meeting of minds and a social contract agreed by all.

And by having their god endorse it, Ur-Nammu gave the people ownership of their religion as well.

Top Image: The great ziggurat of the city of Ur, where the code was written. Source: Ameeryahya84 / CC BY-SA 4.0.

By Bipin Dimri