Ninety years ago, Idaho farmer William Beard, along with his son, discovered something that offered tantalizing evidence of a legendary tale from the past. On one fine morning, in the early 1930s, the father-son duo was busy digging a field in Tetonia, Idaho, which lies on the west of the Teton Mountain Range. While working in the field, they uncovered a rock of rhyolite lava, which appeared to be carved in the shape of a man’s head. On this stone was carved “John Colter 1808”.

Evidence of a Legendary Tale

With this discovery, the first evidence was provided for what had previously been considered an unbelievable story of a man’s victory over death. John Colter, or for some “the first Mountain Man”, is considered a legend. This pioneer and explorer is credited with the discovery of Yellowstone National Park, especially the Geyser Basin, which is popularly known to this day as “Colter’s Hell”.

What makes Colter’s journey especially fascinating is his desperate escape from the Native American Blackfeet (or Blackfoot) tribe. But before the historic chase which made Colter a legendary figure, his story of expeditions and adventures began in the year 1803.

Where It All Started

On October 15, 1803, Colter met Captain Meriwether Lewis and was enlisted in the Corps of Discovery with Lewis and his friend, Second Lieutenant William Clark, at a stipulated pay of US $5. For the expedition, all the members were enlisted in the US Army’s First Regiment, including Colter.

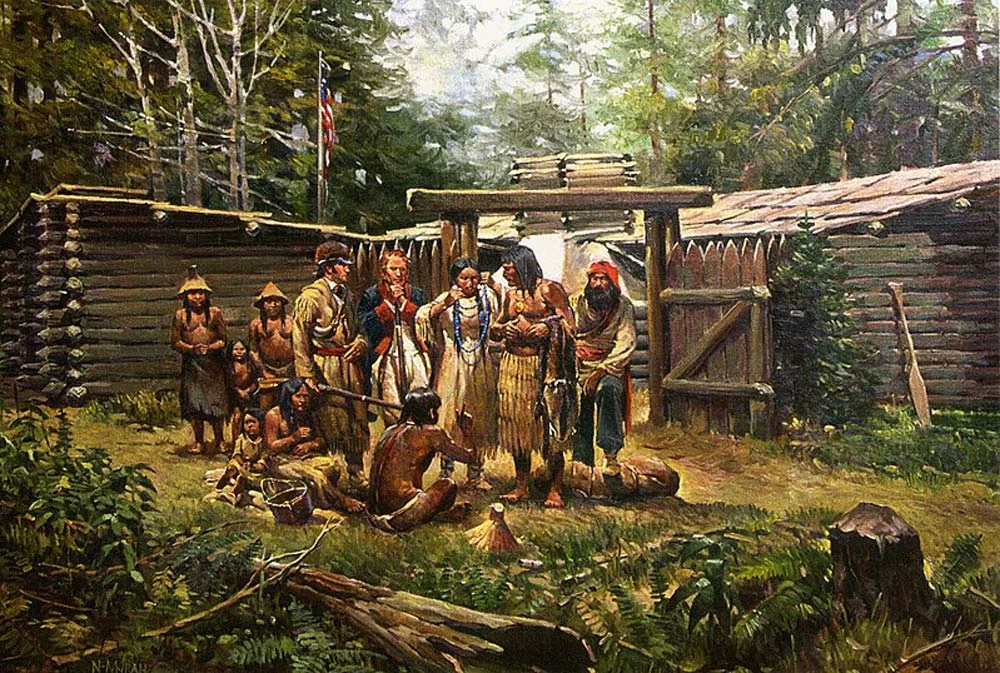

Lewis and Clark’s winter camp at Fort Clatsop. (inkknife_2000 / CC BY-SA 2.0)

There is no detailed information on the qualifications Colter had, as Captain Lewis’s diary is missing any entry about this. But we do get to know of Colter in 1809 through the journal of General Thomas James, who enlisted Colter on a later expedition. James described Colter as ready for hard endurance, and that he had a strong build and was fit for the role.

Colter’s Call of Destiny

In August 1806, when the Corps of Discovery’s return trip had reached the Mandan villages and all the expeditioners were eagerly anticipating the comforts of home, John Colter changed his mind. Two trappers, Joseph Dickson and Forrest Hancock were heading up the Missouri River and invited Colter to join their expedition. Colter agreed and the three men headed up to Missouri on August 17. They reached Yellowstone country, but eventually, the three trappers split up and Colter headed on to St Louis, all alone.

While returning in 1807, Colter encountered the expedition of fur trader Manuel Lisa, a founder of the Missouri Fur Trading Company, which was travelling towards the Yellowstone River. Colter was delighted to see his old comrades from the Corps of Discovery expedition in Lisa’s company, these included John Potts, Richard Windsor, George Drouillard and others. Colter took up the role of free trapper in Lisa’s company, responsible for fur trapping for pelts. Although St Louis was only a week’s travel away, he chose to return to the wilderness to assist Lisa in building the trading post of Fort Raymond.

Colter’s Hell

From this point, the trail of Colter and history seems wrapped up in a blanket of haze, with no direct evidence of the events Colter claimed to have happened. In later 1807 he embarked on his most famous and marvelous journey of discovery into what is now Yellowstone National Park, although unfortunately he kept no written record at the time.

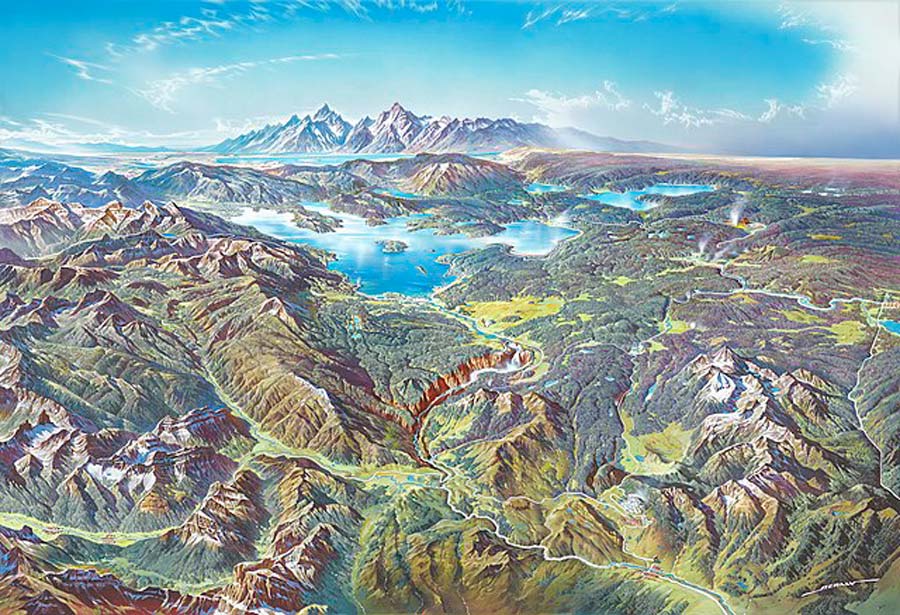

Yellowstone National Park panorama (Heinrich C. Berann / Wikimedia Commons)

Even in the absence of such evidence, “Colter’s Route” released by Colter in 1807 and William Clark’s “Map of the West” has helped researchers reconstruct Colter’s likely path into Yellowstone, along with his discovery of “Hot Spring Brimstone” across the Yellowstone River’s sulfur beds crossing, and the “Boiling Spring”, close to the Stinking Water.

When Colter returned and narrated his discovery of Yellowstone National Park and the wonders he saw, his story was met with near-universal disbelief and his discoveries mockingly called “Colter’s Hell”. Today it is thought that “Colter’s Hell” was likely located outside Cody in north west Wyoming, but the term was also used to refer to Stinking Water, which was an active geothermal area in the Yellowstone National Park’s north-western section, as mentioned by writer Washington Irving. To add to the confusion, in 1895, the Geyser Basin was also referred to as “Colter’s Hell” by Hiram M Chittenden, likely erroneously, and this passed into public use.

The Blackfeet

The Blackfeet were the most powerful Native American tribe in the region and were armed with modern weapons which allowed them to dominate the weak, less powerful tribes. The Blackfeet had a monopoly on the local Native American trade, and hence they were upset when they came to know that Clark would be trading with the Flathead and Shoshone tribes. At about this time, Lewis had a small skirmish with the Blackfeet, while on the Corps of Discovery expedition’s return voyage, which marked the beginning of 35 years of war between the settlers and Blackfeet.

Six Blackfeet Chiefs, 1859 (Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons)

In 1808, for the first time, Colter encountered the hostile Blackfeet, while he was accompanying the Flathead tribe. He instantly captured the Blackfeet’s attention, when he was seen killing a warrior, who was trying to steal horses, and hence, the Blackfeet sought revenge on the “White Man”. Colter was now a marked man.

Colter’s Capture

A year later, Colter, along with John Potts, was canoeing in the Missouri’s headwaters. While they were paddling their way up the Jefferson River, they saw Blackfeet warriors emerge on the east bank in large numbers. Seeing more than 200 Blackfeet warriors, Colter decided not to go for his rifle, and turned the head of the canoe to the shore. Colter and Potts were within the range of the Blackfeet rifles, and hence had no option but to surrender.

As soon as they touched the shore, Potts’s rifle was seized by a Native American. Colter retook the rifle and returned it to Potts, who tried to use it to push the canoe off into the river. When he was unable to do so, Potts levelled his rifle at the Blackfeet and shot a Native American. Instantly, his entire body was pierced by multiple bullets and he fell dead, or as Colter’s phrased it, “he was made a riddle of”.

Missouri River, Montana (Lankyrider, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Potts’ body was taken by the warriors, scalped and then mutilated, as Colter continued to look on at the horrifying scene. Having recognized who their captive was, the Blackfeet took him to a nearby camp, where the trapper was stripped naked. Following the customs of the Blackfeet, it was decided that Colter would not be killed outright as he was a brave man. As the tribe’s chief asked Colter how fast he could run, Colter understood that he would have to now run for life. They were going to hunt him down.

The Famous “Colter’s Run”

The unarmed, naked Colter was released with a minimal head start, and as soon as he heard the war cry behind him, he ran at a tremendous, unbelievable speed. Colter was a powerful runner and in great shape, moving so quickly that he outdistanced the pursuing Blackfeet. As he ran through thorns, sharp rocks, and tough terrain, his feet were shredded and mangled beyond recognition but he managed to save himself from the lethal range of the bullets the Blackfeet warriors fired at him. His exertion was so extreme that blood gushed from his nostrils, freely bleeding down his front.

However, a single Blackfeet warrior, carrying a spear, was able to catch up with Colter. Seeing the warrior gain on him, Colter suddenly stopped, and as the warrior tried to stop, surprised by Colter’s move, he fell on the ground and his spear broke in his hand. Grabbing the pointed part of the spear, Colter pinned the warrior down with it, and continued to run.

Reaching the border of the fork in the river, he jumped in the water and hid himself in a raft of drift timber. He floated down the river silently in the night and covered some distance. After he felt sure he had eluded his pursuers, he climbed up the bank of the river and continued his escape over land.

After seven days’ travel, he reached Lisa’s fort, unrecognizable, completely naked, having survived on roots and with his feet soles filled with thorns. The company at first failed to recognize him until he introduced himself. The incident was later retold and made famous by British naturalist John Bradbury in 1817, in great detail.

The Mountain Man Settles in Civilization

Feeling that he had exhausted his fair share of luck in surviving the wilderness, Colter decided to travel back down the Missouri River and settle in more civilized surroundings There he stayed until he died, most likely of jaundice in 1812 or 1813. His stories lived on in folklore but with no evidence or record at the time many considered the story of his escape fanciful, until the fateful unearthing of a stone head and the inscription “John Colter 1808”, 90 years ago.

Top Image: John Colter’s adventures have passed into legend. Source: subinpumsom / Abode Stock

By Prisha

References:

Vinton S. 1926. John Colter, discoverer of Yellowstone park.

Mattes M. 1962. Colter’s Hell & Jackson’s Hole : the fur trappers’ exploration of the Yellowstone and Grand Teton Park Region.

Rutter M. 2005. Myths and mysteries of the old West.

Harris B. 1993. John Colter, his years in the Rockies.

Nolting M. March 21, 2014. Across the Fence: John Colter, the first mountain man. Available at: https://www.suntelegraph.com/story/2014/03/21/community/across-the-fence-john-colter-the-first-mountain-man/3833.html

Fifer B. John Colter. Available at: http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/2613