We like to think our governments create legislation to protect us, using it as a tool to ensure the betterment of society. But sadly, history shows us that often the opposite has been true, with legislation being wielded as a weapon of discrimination.

A classic example is Britain’s 19th century Contagious Diseases Act, a reminder of the gender biases that were once ingrained in society’s very fabric (and, lamentably often still are). This legislation epitomizes the systemic sexism that prevailed during that era and served as a tool for oppression. The Act had a profound impact on women’s lives, persecuting them in the name of public health.

What was the Contagious Diseases Act?

The Contagious Diseases Act, or CDA for short, was a piece of 1860s legislation that left a dark mark on 19th-century Britain. First introduced in 1864 but later extended, it was framed as a way to combat the spread of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among Britain’s armed forces.

The Act came from a genuine need, with STDs in the armed forces arguably reaching epidemic levels. But the Act also authorized the police to detain any woman suspected of being a prostitute and forcibly subject them to invasive medical examinations.

Under the CDA, designated areas near military bases, known as “contagious diseases districts,” became hotbeds of regulation and discrimination. In these areas, women were subjected to levels of scrutiny that simply were not applied to men.

Any woman found to be carrying an STD could be detained and locked in a hospital for treatment. This often meant weeks or even months of confinement in awful conditions.

Although sold to the public as a measure to protect the health of servicemen, in reality, the Act really targeted women and assumed they were disease carriers. This inherent bias would have far-reaching consequences, perpetuating harmful stereotypes and legitimizing the mistreatment of vulnerable women in society.

The Contagious Diseases Act, in essence, was a tool that institutionalized sexism and sanctioned the violation of women’s rights under the guise of public health concerns.

The Excuse

So why was such a controversial piece of legislation even introduced in the first place? Well, the 19th century was a period during which the British Empire was rapidly expanding across the globe. As such, its immense military was also expanding.

The British Empire was massively reliant on its military and the fear of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), particularly syphilis and gonorrhea, spreading among the military ranks was a genuine concern. The prevailing belief was that prostitutes were the primary carriers of these diseases, and the military authorities sought to address this perceived threat to the health and efficiency of the armed forces.

The original versions of the CDA only applied to certain military garrison towns like Portsmouth and Aldershot. As mentioned earlier, the act gave local authorities the ability to arrest suspected prostitutes, test them for STDs, and lock them up against their will in hospitals.

Supporters of the CDA claimed it was a necessary evil in order to protect the health of servicemen, reduce the prevalence of STDs within the military, and maintain military readiness. Critics pointed out how flawed the Act was. It focused solely on women and reinforced gender biases, demonizing them. It also completely ignored the fact that it takes two to do the horizontal tango.

The CDA’s introduction may have been rooted in genuine concerns about public health, but it is clear it ultimately served as a vehicle for institutionalized sexism and the violation of women’s rights.

None of this means that the legislation as enacted was acceptable, however. The government may have claimed the CDA was brought in to protect the military and public health but in reality, it was a manifestation of deeply ingrained gender bias.

One of the most glaring aspects of this bias was the Act’s disproportionate and discriminatory focus on women. The treatment of women under the CDA was not just archaic, it was completely open to abuse. The police had the authority to detain women on mere suspicion, no evidence required.

It is easy to see how this led to widespread abuses of power. In essence, the police could pick up and “examine” whatever women they liked. Once in custody, these women were subjected to degrading and invasive medical examinations, including vaginal and uterine inspections. Such examinations violated their privacy and dignity in the name of “public health.”

- John Hunter: Syphilis, Hubris, and the Great Misbegotten Experiment

- Toxic Leadership: Did the US Govt Poison Prohibition Alcohol?

The real kicker however was the fact that men, who were equally responsible for the spread of STDs basically remained unaffected by the Act. They weren’t subjected to the same level of scrutiny, they weren’t rounded up by the police, and they weren’t forcibly examined.

In essence, the Contagious Diseases Act not only failed to address public health concerns effectively but also systematically discriminated against women, perpetuating harmful gender stereotypes, and subjecting them to humiliation and abuse in the name of medicine and morality.

Much of the abuse came from the fact the police were free to take in women on mere suspicion of engaging in prostitution. This essentially led to profiling where women could be stopped and examined just because they looked a certain way, came from a certain social class, or were unaccompanied in a certain area.

There was also next to no accountability in the system. The medical examinations carried out under the CDA were often conducted without proper consent, violating the rights and dignity of the women involved. Moreover, there were instances of unscrupulous doctors exaggerating or falsifying STD diagnoses to keep women in “lock hospitals” for extended periods, sometimes months on end.

During this period if you wanted to get rid of a certain woman all you needed to do was report her as a prostitute. With the right connections, you could make her disappear for months on end and destroy her reputation at the same time.

The act did little to actually address the root causes of prostitution at the time- poverty and limited employment opportunities for women. Instead of addressing the social issues that led some women into sex work, the CDA focused solely on punitive measures against them.

The Contagious Diseases Act, though born of genuine concerns about public health, became a symbol of institutionalized sexism and abuse of power. Its discriminatory focus on women, arbitrary detentions, invasive examinations, and perpetuation of harmful stereotypes underscored its inherent flaws.

While ostensibly aimed at curbing sexually transmitted diseases, it failed to address the root causes and disproportionately punished women. The CDA’s legacy serves as a stark reminder of the lengths to which society can go when prejudice masquerades as public health policy. As a society, we must be ever vigilant against legislation that claims to be for the greater good but can just as easily be used to oppress.

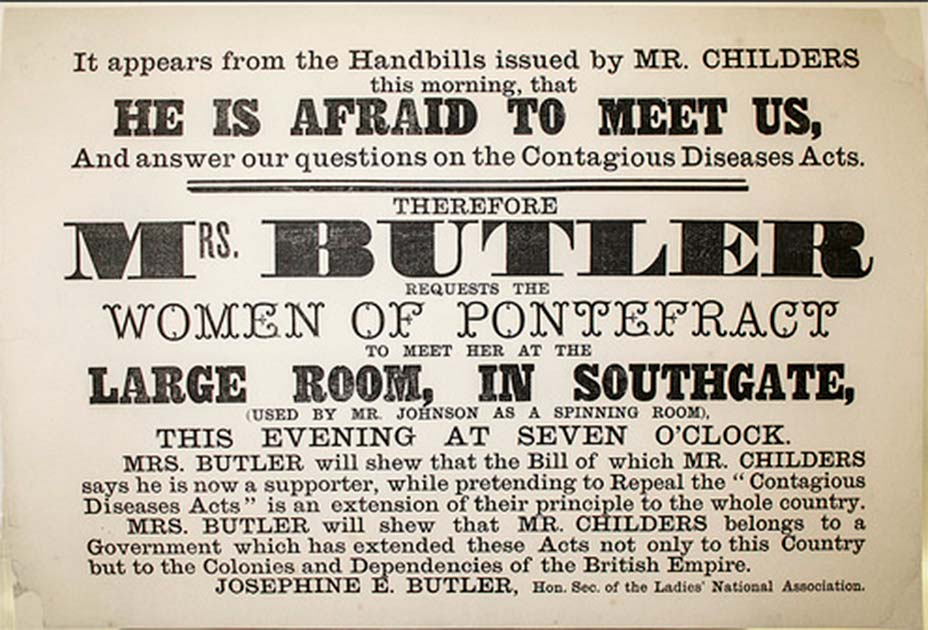

Top Image: The Contagious Diseases Act may have been well-intentioned, but it exposed a deeply sexist way of thinking in British society and was open to egregious abuses. Source: John Leech / Public Domain.