Surprisingly, human fat has been mentioned in pharmacopeias, books filled with medicines and medical advice, since the 16th century. It was described as an important component for ointments and other medicines.

It was often used alongside other fats from animals. Most people tend to hear about the medicines featuring animal products that date back to ancient Egypt but the history of human fat and its use in medicine has been obscured.

That is until recently. A recent book by Christopher E Forth in 2019 has brought to light some of the more unusual aspects of human fat. In the book Fat: A Cultural History of the Stuff of Life he claimed that in 16th and 17th century Europe, a specific interest was being developed in using human fat for medicine.

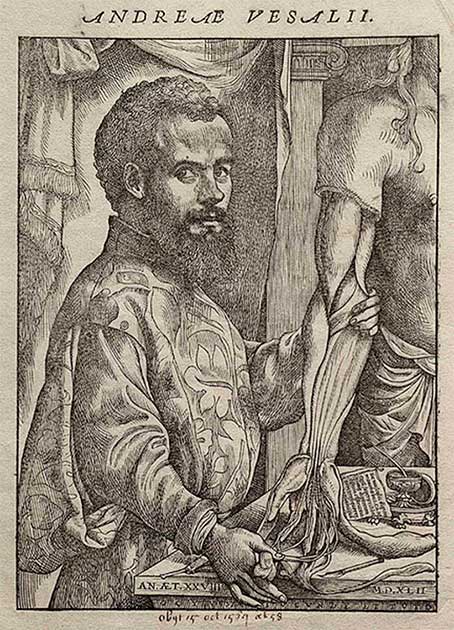

Andreas Vesalius, a physician, instructed many people who were boiling bones before they examined them, that they should save the fat for the benefit of the general public. He believed that it could be used to help scars fade and help nerves and tendons grow and repair themselves.

After a battle in 1601, at the Siege of Ostend in Belgium, Dutch surgeons visited the battlefield to harvest bags of fat likely to use the fat to treat any survivors. It seemed that the health benefits trumped any squeamishness about using it.

Medicine from Corpses

The use of dead bodies can be traced back to the days of the Roman Empire, but it was not that widespread. It is first mentioned in 25 AD. There are some indications that it was used across Europe in the Middle Ages but it was not organized until the 16th and 17th centuries.

It only lasted until the 1890s. Physicians regularly experimented with corpse-derived medicines. It was suggested that they could be a medicine for anything from deep wound scars to gout. Some of these recipes can still be found today.

- Mummia Medicine: Did Europeans Eat Ancient Egyptian Mummies?

- Jaw-Droppingly Awful? The Radioactive Medicine of the 1920s

Roman writers claimed that drinking gladiators’ blood after they had been freshly killed, would strengthen the drinker. Some claimed that applying moss found on skulls could stop fresh wounds from bleeding.

In order to promote hair growth, for those who had a struggling hairline, a “liquor of hair” (gross) was developed. Powdered hair was recommended to cure jaundice. Cataracts could be fought by grounding excrement into a powder that you could blow into your eye.

A belief circulated across Europe that eating ground body parts and bodily fluids would combat other bodily problems. A 16th-century Swiss physician named Paracelsus was hailed as the “father of toxicology” and advocated that in order to cure an ailment, you needed something that was similar.

This was how they justified corpse medicine. In order to fix the body, you needed pieces of the body. However, it did not always need to be eaten or ground up. He believed that if you suffered from a toothache then you would want to wear a tooth around your neck. If you were feeling risky, you could touch the healthy tooth of the corpse of your ill one, and it may just heal the tooth rot.

This fascination with medicine interested all standings of society. From paupers to kings, they were all interested in the corpse medicine business. A key figure who was interested in his medicine was King Charles II of England.

He reportedly used the “King’s Drops”, a medicine which was made from a human skull. All it required was for you to powder a human skull into a bag of fine dust, add alcohol to it and drink it. Charles II used this medicine even on his deathbed along with other herbal remedies but all failed.

Whilst Charles II died, his medicine lived on. It was sold in shops across London, through the 18th century. It was adapted slightly, some physicians would add chocolate or herbs to the mix all in the hope of curing epilepsy, and bleeding and preventing death.

Where did they Get the Bodies?

There was a whole host of places where these physicians could source the bodies. Some were shipped over from Egypt as mummies, whilst others encouraged mummification to happen at a local level.

Depending on the social standing of the person when they died, their body may be used for different medicines. A great source of bodies and body parts was often an executed criminal or a poor person who likely died through overwork and starvation.

However, a premium medicine would require a premium body. In the UK, Irish workers and dead were great sources of bodies. They were colonized and maligned by England and thus there were lots of opportunities to source parts.

Corpses were also taken back from wars and criminal executions. The more violent deaths were seen to give the body more medicinal power. Dissection and corpse medicine became intertwined socially as bodies were dug from the ground.

Some doctors drew the line at taking bodies from graves marked by families. They tended to focus on unclaimed bodies. However, not everyone was able to have a readily available supply of bodies in an unmarked grave. Thus, they had to turn to other supplies.

In the 17th century, recipes began to emerge for mummification. Johann Schroder claimed that “Take the fresh, unspotted cadaver of a redheaded man (because in them the blood is thinner and the flesh hence more excellent) aged about twenty-four, who has been executed and died a violent death. Let the corpse lie one day and night in the sun and moon—but the weather must be good. Cut the flesh into pieces and sprinkle it with myrrh and just a little aloe. Then soak it in spirits of wine for several days, hang it up for 6 or 10 hours, soak it again in spirits of wine, then let the pieces dry in dry air in a shady spot. Thus, they will be similar to smoked meat, and will not stink.”

Put another way, this encyclopedia of treatments allowed by a certain frugality when it came to using the bodies. It allowed the physicians to use every available piece available to them, hopefully drawing out the time before they had to go and get another corpse.

This may all seem positively ghoulish to the modern ear, or at the very least extremely misguided. However corpse medicine lasted for hundreds of years, and it can still be seen today, albeit in different forms. Early corpse medicine led to advancements in organ donations and skin grafts.

Top Image: Corpse medicine developed alongside anatomy as doctors hoped to put the human body to use in helping the sick. Source: Michiel Jansz van Mierevelt / Public Domain.

By Kurt Readman