Almost all of what was written throughout human history has been lost. The further back we travel in time from the present day, the more has gone missing. Eventually, the fact that anything survived at all becomes remarkable.

So it is with the Derveni papyrus, an ancient Macedonian papyrus roll first rediscovered in 1962. It is a philosophical treatise written in the circle of the philosopher Anaxagoras as an allegorical commentary on an Orphic lyric, a theosophical text about the origin of the gods.

But what makes the papyrus so special is that it is Europe’s oldest surviving text. Furthermore, it was written around 340 BC, during the reign of Philip II of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great. The poem was written near the end of the 5th century BC, and it is unquestionably the most important textual find of the 20th century in what it can tell us.

It provides a unique insight into the world of almost 2,500 years ago, the disciplines of Greek religion and western philosophical thought that developed from it, the sophistic movement, early philosophy, and the foundations of literary criticism. It offers an alternative to Socratic wisdom which it predates, and demonstrates universal human constants in needing to understand the world, cooperate with our fellow humans, and face death in sorrow.

So, what does it have to say?

Where Does the Derveni Papyrus Come From?

The roll was discovered on January 15, 1962, on the road from Thessaloniki to Kavala in Derveni, in Macedonian Greece. The location is a nobleman’s grave in a necropolis that was once part of a large cemetery in the historic city of Lete.

- Oxyrhynchus Papyri: Historical Treasure in Ancient Egyptian Garbage

- Linen Book of Zagreb – A Mummy With Etruscan Ties

It is the oldest surviving manuscript in the Western tradition, as well as the only ancient papyrus known to have been discovered in Greece. Regardless of location, it could also be the oldest extant papyrus written in Greek.

The papyrus text comprises a mixture of dialects, mostly consisting of three forms of Greek: Attic, Ionic and occasionally Doric. The texts overlap slightly between the three dialects, and there are phrases and terms which are repeatedly on more than one language, with several variations.

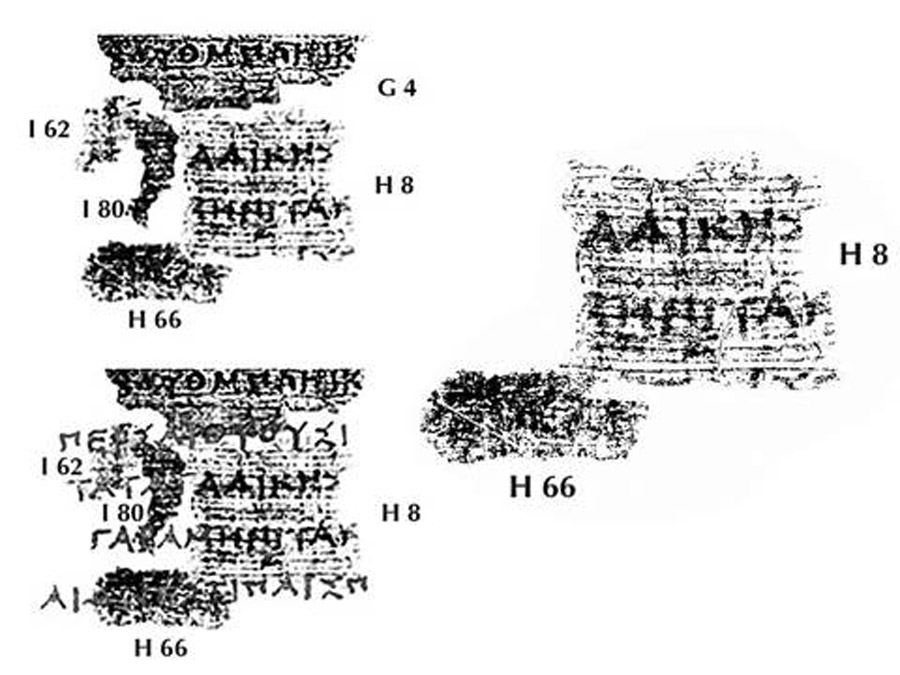

The top sections of the damaged papyrus scroll and fragments were retrieved from ashes atop the tomb slabs by archaeologists Petros Themelis and Maria Siganidou; the lower parts had burned away in the funeral fire. The scroll was painstakingly unrolled, and the fragments were reassembled to form 26 columns of text.

Because it was carbonized (and hence dried) in the nobleman’s funeral pyre, it survived in the damp Greek soil, which is ordinarily unsuitable for papyri preservation. However, the papyrus itself was still very difficult to read for several reasons.

Both the ink used and the background to the paper is black, which makes deciphering individual words a slow and painstaking process. Furthermore, it exists in the form of 266 fragments, which are conserved beneath glass in Thessaloniki’s Archaeological Museum. The fragments are held in descending order of size and have had to be meticulously rebuilt, and many smaller fragments are yet to be placed.

What Is Written On It?

The majority of the text is a commentary on a hexameter poem attributed to Orpheus that was utilized during initiations into the mystery cult of Dionysus. On the papyrus the poetry’s fragments are quoted, followed by interpretations by the text’s main author, who tries to illustrate that the poem doesn’t mean what it says literally.

“Close the doors, you uninitiated,” begins the poem, a renowned warning to privacy also referenced by Plato. According to the ancient commentator, this proves that Orpheus created his lyric as an allegory.

Nyx (Night) gives birth to Uranus (Sky), who becomes the first monarch, according to the poem’s narrative. Kronos succeeds Uranus as ruler, but he, too, is followed by Zeus, whose dominion over the entire universe is praised.

Zeus draws some of his authority and power by hearing oracles from Nyx’s sanctuary, who tell him of the future and allow him to be forewarned. Zeus rapes his mother Rhea at the end of the book, which, according to the Orphic theogony, will result in the birth of Demeter.

Zeus would then have raped Demeter, giving birth to Persephone, who would eventually marry Dionysus, a clear break from the mainstream tradition where she marries Hades. This part of the story, however, must have continued in a second roll that has since been lost.

Orpheus, according to the poem’s translator, did not intend any of these episodes to be literal, but rather allegorical. The text’s initial surviving columns are less well preserved, but they discuss occult rituals like sacrifices to the Erinyes (Furies), how to get rid of demons that have become a problem, and spells.

They incorporate quotes from Heraclitus, the Greek philosopher. Even the arrangement of the fragments is questioned, making their restoration exceedingly contentious. Valeria Piano and Richard Janko, who notes elsewhere that he has discovered that these columns also include a passage from the philosopher Parmenides, have lately given two different reconstructions.

A Window Into Ancient Thinking?

In this text we therefore have an ancient tradition, the initiation into a mystery cult, and a contemporary reading and criticism of the text. There’s a lot here for philosophers to learn about Greek religion, papyrus studies, and, most importantly, the fluidity and interconnectedness between philosophy and theology, science, and superstition in ancient Greek society.

The Derveni papyrus is a fascinating new Greek literary document. It is possibly the only papyrus ever discovered on Greek territory, and if not the oldest Greek papyrus ever discovered, it is certainly the oldest literary papyrus, dating from around 340 to 320 BC.

Sadly, given the unusual context of its preservation and the damage done to papyrus by European soils, it is likely that there will be no others. It was only chance that this single manuscript survived to offer us an insight into the thinking before Socrates and Plato.

Top Image: What can the Derveni papyrus tell us about ancient Greece? Source: Shaiith / Adobe Stock.

By Bipin Dimri