Mountaineering is a dangerous and physically demanding hobby, but some fantastic mountains can be conquered. There are many intense peaks in the Himalayas, one of the most challenging climbs is K2, also known as the “Savage Mountain”.

This is the second tallest mountain in the world, and the infamous “Bottleneck” section sees climbers traverse large swaths of glacial ice. Someone can only climb K2 so far before reaching the “death zone,” which is an altitude of 8,000m, where human life can only briefly be sustained.

There is Denali in Alaska, a high altitude, isolated, poor weather, and low temperatures climb up the tallest mountain in North America. The mountain has a 50% success rate of climbers reaching the summit, but many mountaineers seek to check Denali off their “To Climb” list.

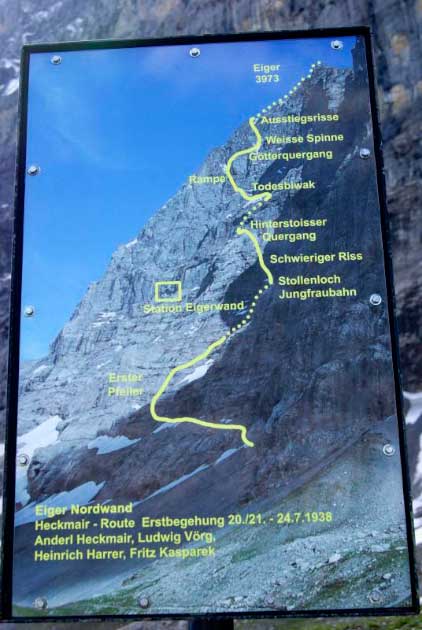

The Alps are in many ways the perfect place to climb, but what tempts climbers the most is Eiger Mountain. The north face of Eiger has earned the nickname “Murder Wall” for a good reason; climbing this face has killed at least 64 climbers since its first successful ascent in 1938.

The Eiger is a mountain that requires enormous skills and expert use of an ice axe. To make it even more of a challenge, avalanches and rockfalls are known to occur pretty often. Why is Eiger’s north face such a treacherous climb, and had anyone tried to climb the mountain before 1938?

The Eiger

Eiger is a 13,015ft (3,967m) mountain of the Bernese Alps that overlooks the villages of Lauterbrunnen and Grindelwald in the canton of Bern, Switzerland. The most notable feature of Eiger is the 5,900ft (1,800m high) northern face of the mountain, a sheer climb of rock and ice.

Eiger’s north face, or Nordwand in German, is the biggest north face in the Swiss Alps. Eiger makes up one of three mountain ridges of the Alps known as the Virgin, the Monk, and the Ogre; Eiger is the standard German word for Ogre.

The north face of Eiger is one of the three significant northern faces of the Alps, along with the northern faces of the Matterhorn and the Grandes Jorasses. While summiting Eiger from other approaches is almost trivial, climbing the north face of Eiger is a technically and physically demanding climb.

The climb is best suitable for intermediate to advanced climbers. To have any chance of success you must be experienced and confident climbing along exposed ridges, 45 to 60-degree ice, and snow slopes. It has a climbing rating of 5.7/5.8, which is used to describe a vertical climb with small and challenging areas for hand and footholds.

Climbing Eiger’s north face takes you through sub-freezing temperatures, and the weather conditions of the Alps are constantly changing. Before attempting the climb, it is recommended that a climber know how the weather in the Alps works and how clouds and storms can linger in the mountains, which can keep someone camped in place for one to several days before the conditions are clear enough to continue.

Many experienced solo climbers and teams of climbers have attempted to scale the north face of Eiger and have been unable to do so. That being said, it is possible to climb to the summit thanks to modern climbing devices and technology.

At a height of 2,866 meters (9,400 feet), inside Eiger mountain is the Eigerwand railway station. This station connects to the north face via a tunnel opening that has often been used as a rescue point for climbers. In 1938, the year of the first successful climb, the editor of the Alpine Journal called the north face “an obsession for the mentally deranged” and “the most imbecile variant since mountaineering first began”.

- The Mystery of Mount Everest: Did Mallory Reach the Top?

- Machu Picchu Facts – 11 Fascinating Details of the Inca Citadel

Other notable features and landmarks on the mountain evoke vivid imagery and clearly portray the dangers of the face. (from the base of the mountain and up). The Eigerwand Station, First Ice-field, Hinterstoisser Traverse, Second Ice-field, the Death Bivouac, the Traverse of the Gods, and the Spider.

The First Ascent of Eiger

The first successful ascent of Eiger took place on August 11, 1858, and was completed by Christian Almer and Peter Bohren guiding Charles Barrington. Barrington wanted to attempt the first ascent up the Matterhorn, but due to a lack of a budget and because he was staying near Eiger, that is the mountain he climbed. This climb was on the west flank of the mountain, not the tricky north face.

The first attempt at climbing Eiger’s north face took place in 1934, but the climbing group only managed to reach a height of 2,900m (9,500 feet). This climb has largely been overshadowed by the earlier 1935 attempt by two German men, Karm Mehringer, and Max Sedlmeyer.

On the first day of their ascent, the weather was poor, but once it cleared up, the duo reached the Eigerwand station, where they decided to stop and create the first bivouac of the journey. A bivouac is a temporary improvised campsite/shelter used by soldiers or people scouting, backpacking, or mountain climbing.

On the second day of the climb, the duo faced lousy weather that saw low clouds and snow on the third night. At this point, avalanches began to happen, a common condition on Eiger’s north face, and the situation became extremely perilous.

One of the horrors of the Eiger is that the entire ascent can be watched in real time from the town below. Unable to help, the observers on the ground watched the two men through the breaks in the weather as they fought their way up the impossible climb.

By the fifth day, Mehringer and Sedlmeyer were seen setting up a bivouac for night five when the weather took a turn for the worst. When the weather cleared several days later, there was no sight of the men.

A German WWI flying ace named Ernst Udet flew around Eiger searching for the missing men; he found Mehringer’s frozen body in an area that has now become known as the “Death Bivouac.” A year later, the body of Max Sedlmeyer was found by his brothers, who were on the mountain searching for the climbers from a disaster that occurred that year.

The 1936 Eiger Disaster

In July 1936, ten climbers from Germany and Austria attempted to climb the north face of Eiger, and the trip was a disaster from day one. Before the climb began, one of the climbers was already dead, killed in a training climb, and as the remaining climbers soldiered on the weather worsened.

After several days, the weather didn’t look like it was going to clear up, and several climbers quit before the trip began. When the weather improved, the four remaining climbers, Andreas Hinterstoisser, Toni Kurz, Edi Rainer, and Will Angerer, set out for the dangerous climb.

During preliminary explorations that took place once the weather cleared at the lowest part of the north face, Hinterstoisser fell 121 feet (37m) but was miraculously not injured. On the second day of the climb, the men experienced a rockfall, and Angerer was hit by a rock just below his shoulder blade and sustained injuries, but the group tried to keep climbing at his request.

On the third day, the group was seen descending the mountain at the Death Bivouac. The group had no choice but to begin their descent because Angerer’s injuries were far worse than initially thought. The group struggled to cross a problematic traverse (now known as Hinterstoisser Traverse), and Hinterstoisser tried for several hours to cross this traverse but could not do it.

On the way up, Hinterstoisser used a sophisticated tension traverse climbing technique. This technique involves a rope fixed tight to the face of the mountain that is kept taut so the climbers can lean on it for balance. The issue was the technique could not be used upon descent, leaving the four climbers trapped on the face.

The group decided to abseil/rappel down from the lower lip of the First Ice Field because a ledge ran along a wall of rock, and if they could reach it, they would have ended up at the Stollenloch entrance to the Eiger train tunnel.

- Firozkoh: In Search of the Legendary Turquoise Mountain

- The “Hand Made Mountain”: Cholula, the Largest Pyramid in the World

At this time in history, belay devices had not been invented yet, forcing the group to use a non-mechanical rappel method known as the Dülferstiz method. The Dülferstiz method became used less frequently after the belay was created.

The four climbers made contact with a rail guard at Eigerwand station, about halfway down their descent, and a climber said everything was going alright. But then, while Hinterstoisser was setting up the last rappel of their descent, an avalanche occurred on the north face of Eiger.

The avalanche took Hinterstoiser with it because he had unclipped from the rest of the group to set up the rappel. His remains were found at the bottom of the mountain several days later. The order in which the following events happened or what caused them is unknown, but at some point Willy Angerer fell and was killed on impact after his body hit the rock face.

Edi Rainer was dragged down with him and died by asphyxiation due to the weight of the rope around his diaphragm (possibly caused by Angerer’s fall and dead weight). Toni Kurz managed to survive the avalanche, but he was stuck hanging on the rope with the bodies of Angerer and Rainer still attached.

After being stuck hanging on the rope from the mountain for three days, Swiss guides tried to rescue Kurz but could not reach him. They did get agonizingly close, near enough to ask Kurz what happened, and he told the guides that one fell down the face of Eiger, one was frozen to death on the rope above him, and another fractured his skull while falling and was hanging onto the rope dead below him.

The guides left to get more help, but when they returned, Kurz was in a bad way. He had spent four nights exposed to the elements, and one of his hands and arm were completely frozen and couldn’t move.

Kurz managed to haul himself back into contact with the face of the mountain after he cut Angerer’s body off the rope below him. Still, the guards could not reach the hypothermic man. They were able to toss Kurz a long rope made of two knotted ropes. Kurz tried to use the rope to reach the guides, but the rope knot could not pass through his carabiner.

After hours of struggling, Kurz began to lose consciousness. The guides reported that the last thing Kurz said was, “Ich kann nicht mehr” (I cannot go on anymore) before he died.

At Last a Success

The murderous reputation of the Eiger was confirmed, but it would not be long before it would finally be defeated. On July 24, 1938, climbers Anderl Heckmair, Fritz Kasparek, Heinrich Harrer, and Ludwig Vörd became the first to ascend Eiger’s north face successfully.

It would be decades before anyone would dare to climb the mountain solo, but the first solo ascent took place on August 2-3, 1963, by a Swiss Mountain Guide named Michel Darbellay. His climb took 18 hours to complete.

In 1964, the first woman, Daisy Voog, became the first woman to make it to the summit of Eiger via its north face; Werner Bittner accompanied her during this climb. The first solo female climber to scale Eiger’s north face was Catherine Destivelle on March 9, 1992. She completed the climb in 17 hours in winter.

The second female to solo climb the north face was Laura Tiefenthaler at the end of March 2022. She was 25 years old at the time of her climb and was able to reach the summit in 15 hours. She had climbed Eiger before with partners but never on her own until that climb. She was inspired by the story and writings about Catherine Destivelle’s 1992 climb.

Today the Eiger has lost much of its reputation, and with modern safety and modern techniques it is more of a plaything for extreme sports. However nobody should forget the dangers of this most intimidating of Alpine mountains.

Top Image: The awe-inspiring North Face of the Eiger. Source: Tobias Marx / Adobe Stock.