Rzeczpospolita, the official name of Poland, is an unfamiliar word to most. Essentially meaning “commonwealth” or “republic”, it was also applied to an earlier country, one larger than any modern European state excluding Russia.

This massive state, some 400,000 square miles (1.04 million square kilometers) in size and with 11 million inhabitants, was formed by the union of Lithuania and Poland during the 16th century. The confederated state known as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth became one of the biggest polities in modern Europe.

The state encompassed territory in modern-day Poland, Russia, Belarus and Ukraine, as well as the three Baltic states. However, during the late 18th century, it disappeared from the map altogether.

So what happened to this European super state?

Meaning of Rzeczpospolita

Initially, Rzeczpospolita was used as a generic term in Polish that denoted a commonness or a state, literally a “commonwealth.” The term was initially coined by translating “res publica,” Latin for “thing of the people.”

The ruling Polish nobility intended the Rzeczpospolita to refer to a state for the common good of its inhabitants. In this way they considered it a development and continuation of the ideals of the Roman Republic.

The 1st Rzeczpospolita

The 1st Rzeczpospolita, or “First Polish Republic” (hereafter called “Rzeczpospolita”) was brought into existence in 1569 following the signing of the Union of Lublin. It replaced the existing states of Poland and Lithuania with a new country ruled by the Jagellion King Sigismund II, the principal architect of the treaty.

But the political structure of the new country was to become very different to those that existed before. With the death of Sigismund only three years later, it was decided that his successor and all following rulers were to be elected from the nobility, ruling for life.

The new Rzeczpospolita was effectively ruled by the “Szlachta,” who had the right to elect the king from among the Magnates (higher nobility), as well as the parliament (the Sejm). The political system was known as the Golden Liberty, and went a long way to reassure the Lithuanian nobility who feared the treaty was essentially an annexation of Lithuania by Poland.

- Cold Hearted: Why Did Empress Anna Ivanovna Build An Ice Palace?

- Crown Prince Rudolph And The Mayerling Incident: Suicide Or Murder?

But Lithuania also feared her huge, bellicose neighbor Russia, and various skirmishes and wars along her frontier had left her fearing invasion. A political treaty with Poland, a powerful neighbor, and one in which the Lithuanian nobility would hold positions of power, was seen as the most practical defense against this threat.

A Modern Country?

The new state was a multi-ethnic country, inhabited by Germans, Jews, Poles, Lithuanians, and Ruthenian Slavs. A small number of Scots, Tatars, as well as Americans also occupied the country. Under the practice of “Sarmatism” (derived from the ancestors of the Szlachta) an attempt was made to integrate and accommodate the multi-ethnic nobility.

Perhaps even more surprisingly at the time, Rzeczpospolita was a multi-faith country where Protestants, Roman Catholics, Muslims, Jews, and Eastern Orthodox Christians lived together within the boundaries.

This liberal approach to faith and social background led to the new state standing in stark contrast to the absolute European monarchies to the west. The Golden Liberty was effectively unprecedented in Europe, and led to the later development of constitutional monarchies as Europe evolved towards democracy.

The 17th Century Crisis

Gradually, power struggles amongst the Szlachta and Magnates started to erode the political system and the rights of individual citizens. The Szlachta emerged as the dominant power of Rzeczpospolita, and the structure of the state was twisted to promote the privileges and rights of the nobility.

This evolving political system led to a gridlock in lawmaking, eventually paralyzing the state. This is most clearly seen with the introduction of the Liberum Veto procedure which allowed for any single noble to block legislation, for any reason.

There were also foreign pressures which damaged the state. Two decades of war against Russia and Sweden during the mid 17th century, combined with an internal Cossack rebellion and decades of epidemics and famines, exhausted and ruined Rzeczpospolita. The population dropped from 11 million to 7 million, especially in the major cities of Warsaw and Krakow.

The crisis affected Rzeczpospolita not only socially but also economically. Agricultural productivity dramatically diminished, resulting in a shortage of labor, destruction of farming equipment and farm buildings, and the loss of cattle stock. International trade also collapsed.

- The Chinese Famines of 1907 and 1959: Natural Disasters or Man-Made?

- Knights of the Golden Circle: A Pro-Slavery Empire

Rzeczpospolita was never able to recover completely after the crisis, as the economic collapse was worsened by the political stagnation. The opportunity to recover, principally through industrialization, was squandered.

The Partitions of Poland

This decline would eventually prove terminal. The start of the 18th century saw Rzeczpospolita surrounded by powerful neighbors, chiefly Russia, Prussia and Austria, who held an increasingly powerful influence over her domestic policies.

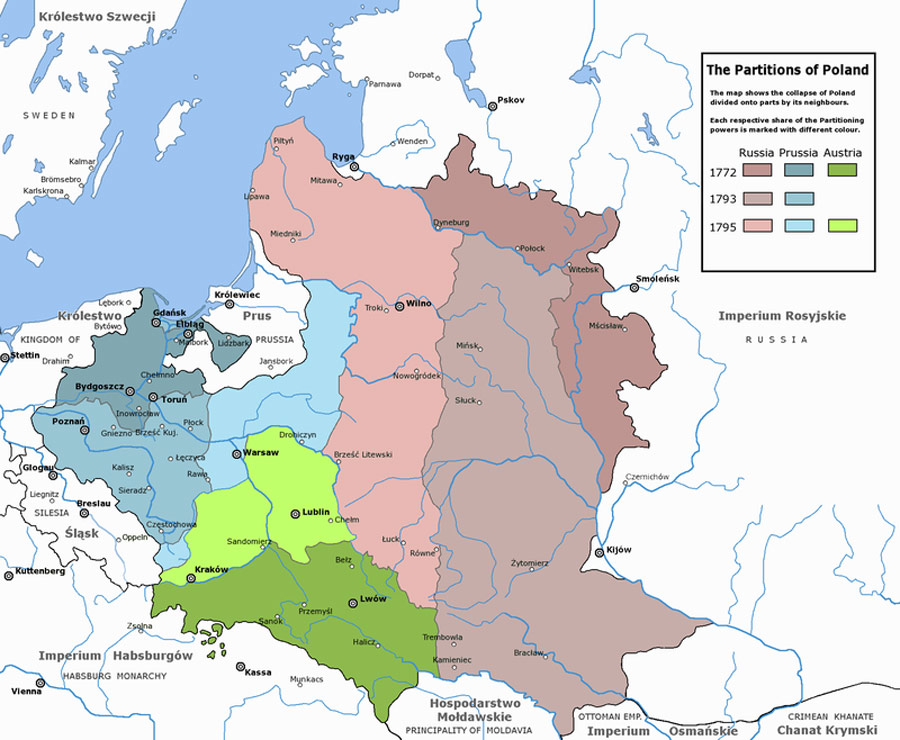

These neighbors were eventually the cause of the end, not just of Rzeczpospolita, but of Poland and Lithuania as well. In the second half of the 18th century, the so-called Partitions of Poland carved up the country, dividing the territory between the Habsburg monarchy, Prussia and Russia.

With the third of these annexations following the defeat of remaining Polish forces at the Battle of Maciejowice in October 1794, the state was finally defeated. Twelve months later the territory was divided between the conquering powers, and Poland and Lithuania would only become sovereign states again at the end of the First World War.

Later “Rzeczpospolita”

There were two more Rzeczpospolita, though neither was as large as the first. II Rzeczpospolita refers to the “Second Polish Republic” that lasted from 1918 to 1939. It refers to the Interwar period, starting from 1918 when Poland regained independence after World War I and ending in 1939, when Poland was invaded by Nazi Germany.

The Second Republic was much more populous, having more than 27 million people on nearly 150,000 square miles of land. A majority of the population depended on agriculture, while industrialization was considered essential to enhance the country’s economy.

III Rzeczpospolita refers to the “Third Polish Republic,” which started in 1989 and continues to date. This is the present-day Polish state.

A State That Looked to the Future

The first Rzeczpospolita was a surprisingly modern state and managed to resist the aggressions of its neighbors for centuries, existing from 1569 to 1795. Build in the idealized mold of the Roman Republic, it sought to balance power between the ruling class and the lesser nobility, provide for its people, and accommodate many different ethnicities and religions.

While there were attempts at reform in the final decades, these came far too late. Destroyed by internal stagnation, which left the state unable to respond to aggressive incursions, the first Rzeczpospolita vanished into history.

But her legacy can be seen today. Her electoral system and tolerance of faith provided the pattern for later constitutional reforms. She was the first step towards a democratic Europe, and through her, the world’s march to democracy continues to this day.

Top Image: Sigismund II Augustus, and the vast territory of Rzeczpospolita. Source: Lucas Cranach the Younger / Public Domain; Mariusz Paździora / CC BY 3.0.

By Bipin Dimri