Magic shows were already massively popular by the 18th century. In the 17th century, many books described magic tricks and were a common source of entertainment at fairs and festivals. As the belief and fear of witchcraft waned, the 18th century saw magic tricks and illusions becoming respectable and were hugely popular to both nobles and commoners alike. But why were people so fascinated by it? And how, in this case, were so many people incensed by it that in London in 1749, they rioted, destroying a theatre and its surrounding area?

Magic Through the Ages

Magic as a performance of tricks had no theatrical significance until the 18th century, yet there were descriptions of magical demonstrations happening in Egypt as early as 2500 BCE. One of the main facets of magic is that the spectators cannot believe the effects of what they have witnessed. The practices of misdirection and psychology have always played a part.

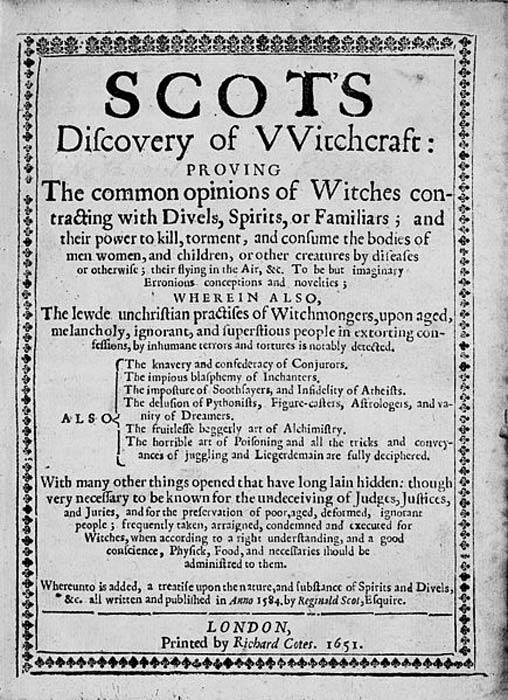

References have existed throughout history, but it is not until the mid-16th century that we see printed literature of magic. Reginald Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft and Jean Provost’s The First Part of Clever and Pleasant Inventions are two of the seminal works on magic. These relay performances of conjurers and the basis of sleight of the hand which is still in use today.

The Rise of the Professional

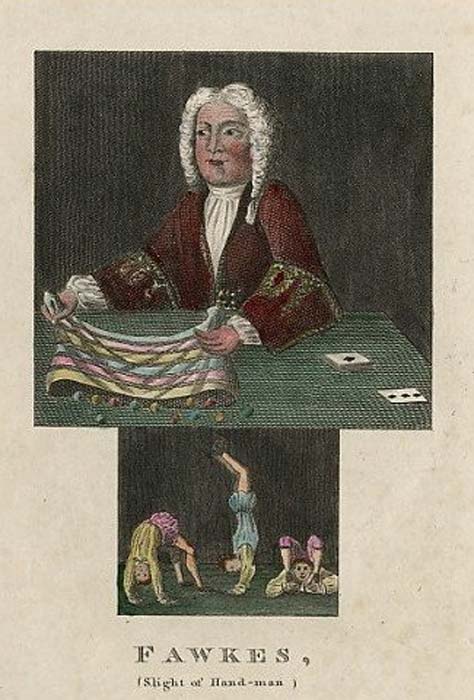

One of the first professional magicians was Isaac Fawkes, an Englishman who performed “surprising tricks by the dexterity of hand” and “curiosities no person in the kingdom can pretend to show like himself”. He was also credited with performing to King George II and other nobility, according to the newspaper articles and advertisements written about him at the time. Research has suggested that the person writing these articles was Fawkes himself, perhaps discrediting these more outlandish claims.

- History of Magic from Dark Art to Pop Entertainment

- Who Was Aleister Crowley…Occultist, Satanist, and British Spy?

Isaac Fawkes became quickly popular in London throughout the early 18th century. Despite establishing his reputation through his self-advertisement, other newspaper journalists began to wax lyrical on his skills. In some papers, they say that he was able to deposit over £700 in his bank account from his exploits as a magician. He even had the arrogance and competitive spirit to challenge others in his profession to achieve the same amount by doing conjuring shows. No one took him up on the challenge.

Fawkes continued to perform at fairs and shows with his son throughout the 1720s until he died in 1732. Isaac was able to leave a fortune of above £10,000 for both his wife Alice and his son. His son continued the business, although Alice had been terrified into confinement after a fire broke out in a neighboring booth whilst he was performing earlier that year.

Clearly, there was a growing enjoyment of these shows, particularly in London. All of this set up what was to be one of the greatest pranks of the 18th century, based on the magic shows of the ancient civilizations and those developed throughout the centuries.

The Great Bottle Conjurer

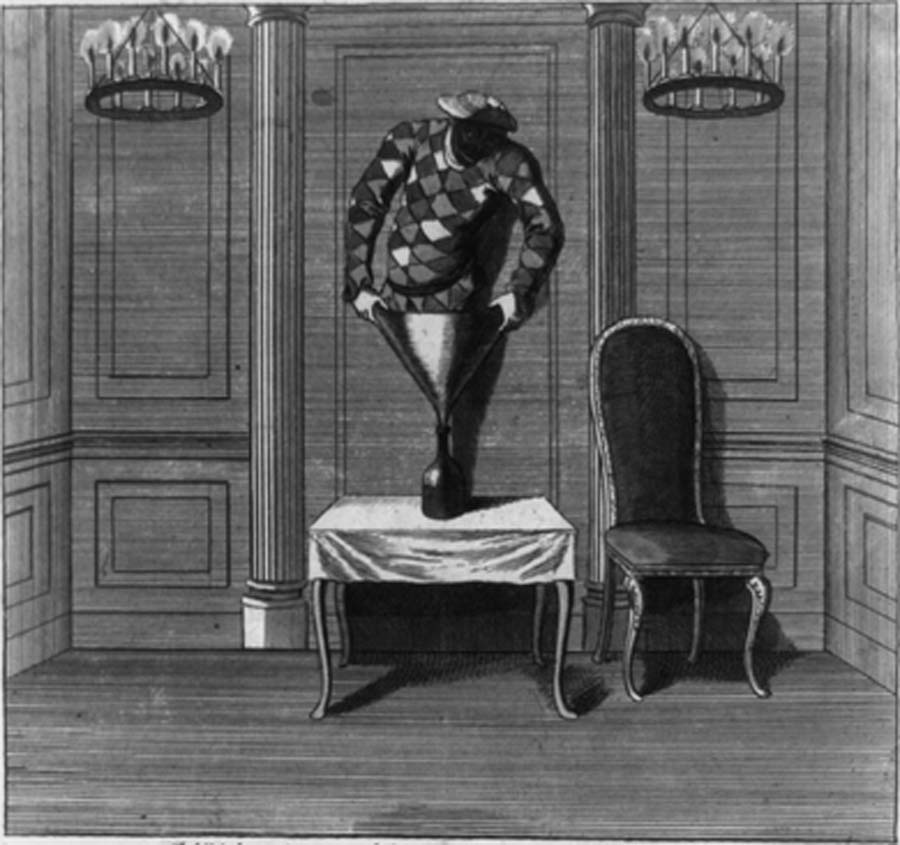

Early in January 1749, a newspaper advertisement appeared offering a show in the New Theatre in the Haymarket. It promised to deliver a person who could perform the most surprising things. Taking a common walking cane from the spectators, he would play the music of any instrument on it perfectly, accompanied by lovely singing. Next, he was to present a common wine bottle, placing it in the middle of the stage and then somehow going into it. The audience could even handle it and see that it was an ordinary bottle.

Unsurprisingly, the people of London were abuzz with excitement to see the latest show, full of tricks that had only been seen by the eyes of kings in foreign lands. On the night of the show, the theatre was packed with viewers all waiting to see the show, from the boxes to the gallery. Yet no magician stepped forward, no matter how long the crowd called and waited.

The Crowd Turns Ugly

As the crowd grew even more restless, an employee of the theatre came out to tell the audience that the performer had not shown. The mob would not be appeased. A gentleman in one of the boxes threw a candle onto the stage. This acted as a signal to the people. They rose, tearing up the seats, benches, and boxes, demolishing everything in sight. Everything that could be carried was taken out into the street to be burned. The night was a disaster.

- “Freak Shows”: P T Barnum and the Circus of Exploitation

- The Stolen Airliner TAAG Boeing 727-223 (N844AA)

Journalists ridiculed the town. Pamphlets were issued mocking the gullibility of the public. Stories even began to circulate that the conjurer had not shown because he had performed a private show where he put himself in the bottle, only to be locked in there by one of the viewers.

Who was the perpetrator?

But who was the mastermind that organized such a hoax? The rumor is that it was a duke who enjoyed such practical jokes. John, the second Duke of Montagu, is said to have stated that if the most impossible thing in the world was claimed, he could fill a playhouse with people who would believe in it. All his friends jumped at the chance to make this bet and challenged him to it. According to this theory, they were behind the advertisement in the paper.

The story soon spread across the nation and throughout Europe. The story became a standing joke on the gullibility of the English nation. This was a particular slight during the so-called age of enlightenment. The great bottle hoax of 1749 has gone down as one of the greatest pranks ever to be played on the public.

Top Image: Historic Magician. Source: Andrey Kiselev / Adobe Stock

By Kurt Readman