As the thinkers of the enlightenment gained insight into the world around them, among other things they became fascinated by the complex machines they called automata. The purpose of these machines was to imitate the living objects, and there were many examples. Among the first was a mechanical duck that ate food and quacked, built by a Frenchman, Jacques de Vaucanson. It astounded people in that it did everything that a real duck would do, yet was a machine!

But, probably the most famous of all examples of automata was the “Great Chess Automaton”. It was built by Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen, a Hungarian engineer, in the year 1769. And his invention took the world by storm.

The Mechanical Turk

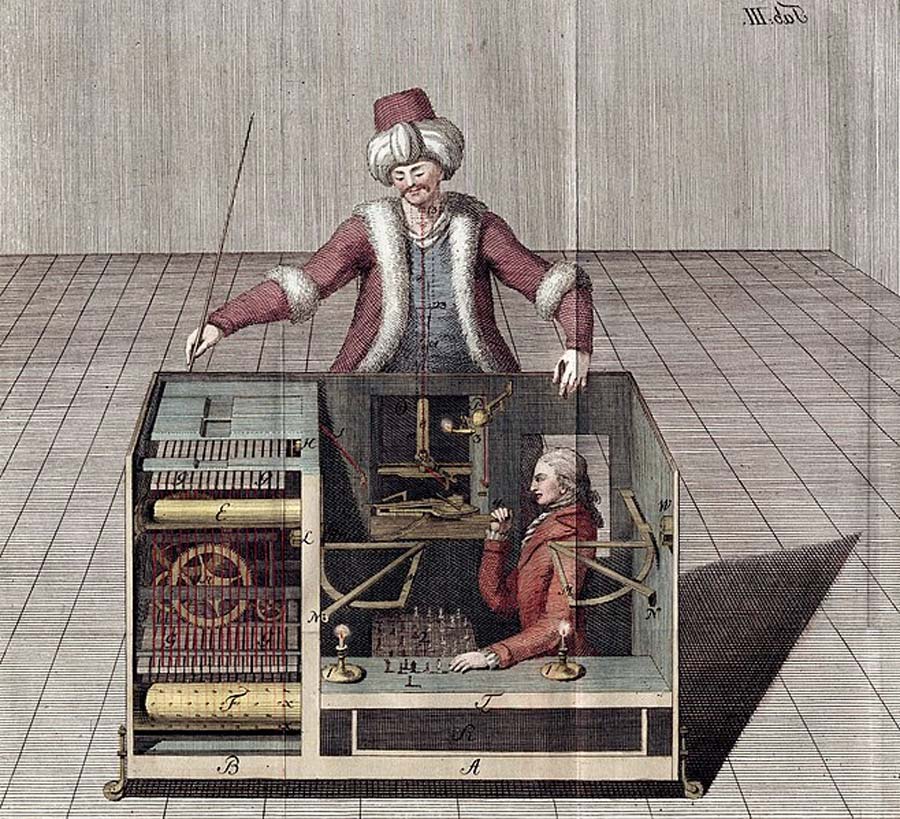

The Great Chess Automaton, also known as the Mechanical Turk, was built in the late 18th century. Von Kempelen presented it as a chess-playing machine, that had the capability of beating even the strongest of chess players. The Great Chess Automaton consisted of a wooden figure sitting at a table with a chess board. The figure was wearing Turkish Clothes, from which it got its name, “Turk”. The trunk of the Turk contained a complex system of wires and gears that allowed the Turk to operate. Once set up, the machine played chess against real opponents.

This was not just a simple automata machine that seemed to play chess. It reacted to the other person’s moves and offered a genuine game of chess to its opponent. Furthermore, the Turk proved to be an excellent chess player, and won many more games than it lost. The Great Chess Automaton was clearly something more than a simple mechanical contraption like the duck, and the inventor named it the “Thinking Machine”, a title it certainly seemed to live up to.

Von Kempelen toured across Europe with this machine and exhibited it in front of large audiences, especially aristocrats and royalty. The inventor challenged his audience to beat his chess player, and the Turk proved itself to be amongst the best chess players. The Great Chess Automaton even defeated Benjamin Franklin, a founding father of the United States, in a game!

Success On The Road

The first performance for the Turk was in 1770, in the Habsburg Court in Vienna. It was presented to the Habsburg ruler Maria Theresa and a large group of her courtiers. From there the exhibition toured with great success for the next twenty years, until the year 1790, when von Kempelen decided to dismantle the Turk and store it.

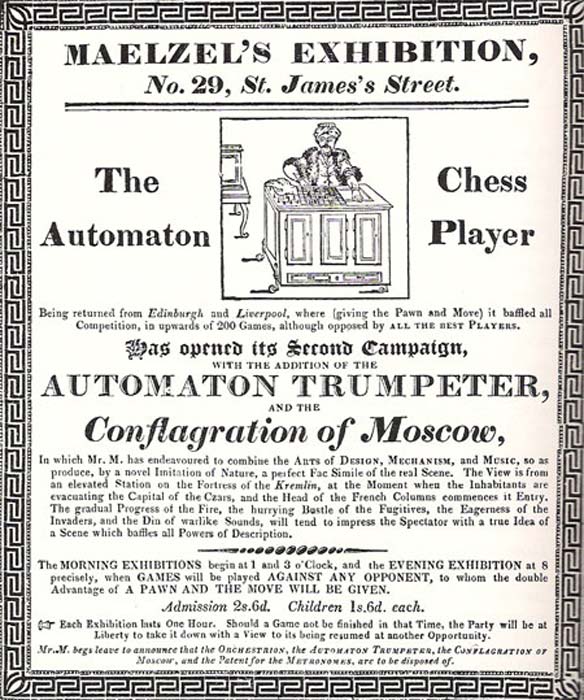

But this was not the end for the Great Chess Automaton, as after Kempelen died in the year 1805, his family sold off the machine to a German University student, Johann Nepomuk Maelzel. He fancied himself a Bavarian showman, and having reconstructed the automaton he took it on a tour of Europe once again.

The machine continued to beat challenger after challenger, to hold onto its title of being the best chess player. In 1809, during the Wagram Campaign against the Austrian army, Napoleon Bonaparte played a game with the Turk, and was defeated by the automaton! Later, it briefly became a part of the private collection of Prince Eugene de Beauharnais, before Maelzel regained its possession in 1817. Maelzel also brought the machine to America 1826 to entertain audiences across the Atlantic.

Suspicions Mount

But there was more to the Turk than met the eye, a hidden secret behind this entire mechanical marvel. The great chess automaton always performed in a systematic manner. Von Kempelen, the inventor, used to make a point before every game of opening the sliding doors of the base of the Turk to show the gears and wires to the audience. This was designed to prove that the area was filled with clockwork gears, and to let the audience see it was purely a machine.

But still, many people suspected someone was hiding underneath the Turk to operate it and guide its chess moves. Unfortunately, there was no evidence to prove this suspicion, and no one could see how it might be done. Some people theorized that a dwarf could be concealed in the base of the device and play the games, but all without proof. There were also many people who actually believed that the Great Chess Automaton was a true thinking machine.

During one of the later shows of the Turk in America, a young man by the name of Edgar Allan Poe got the chance to witness it. He wrote an article upon his experience about the logic and mystery hidden behind this Great Chess Automaton. He himself theorized that there was a man hiding underneath the Turk’s body to play the games. He was convinced his theory was correct, but he also lacked any proof.

- Secrets of the Coral Castle, Florida: An Engineering Marvel

- Was The Nikola Tesla Death Ray a Real Possibility?

A Ghost In The Machine?

But still the exhibitions continued until 1837, when Maelzel and another man named Schlumberger died from yellow fever while returning from Havana to the USA. Then, on February 6th 1837, 70 years after it was created, the Philadelphia National Gazette Literary Register revealed the secret of the Great Chess Automaton.

The newspaper reported that a full-sized man could be concealed within the base of the automaton, and direct the chess moves of the Turk, and that this Schlumberger was the most recent operator. The identity of the people playing behind the face of a Turk varied over time, but it was reported that von Kempelen and Maelzel both preferred to use chess champions for the game. And it was one of those champions who eventually exposed the Great Chess Automaton, after the secret had been kept for 70 years.

Although not certain, the two most likely operators, apart from Schlumberger, were men called Aaron Alexandre and Johann Allgaier. There were a series of sliding panels built into the Turk, and a rolling chair was installed to allow the operator to hide during the display of the automaton’s interior. The operator then preferred to use a pantograph device to sync his arm movements to that of the Turk. The chess pieces were magnetic, which helped the operator follow the game of chess accurately from within the device.

So, the Great Chess Automaton was a hoax after all, and not a thinking machine. The mystery was gone, and the device faded from view as public interest waned. Sadly, a few years later in 1854, the Great Chess Automaton was destroyed in a fire, and passed into history as one of the most enduring deceptions in history.

Top Image: The Great Chess Automaton with internal workings displayed to the audience. Source: Joseph Racknitz / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri