The gold and silver rushes in 1848 in California, and 1859 in Nevada set the American West on fire. Thousands of prospectors hoping to find wealth in the rocky mountains of the West began to move to the West Coast of the US.

Mining towns like the famous Tombstone, Arizona, popped up, and bankers began to create mining companies to make millions of dollars for themselves and other investors. This greed and mining frenzy was the perfect environment for the Great Diamond Hoax of 1872.

This hoax was considered the “most gigantic and barefaced swindle of the age,” but what actually was it? What happened during the Great Diamond Hoax of 1872?

A Cunning Plan

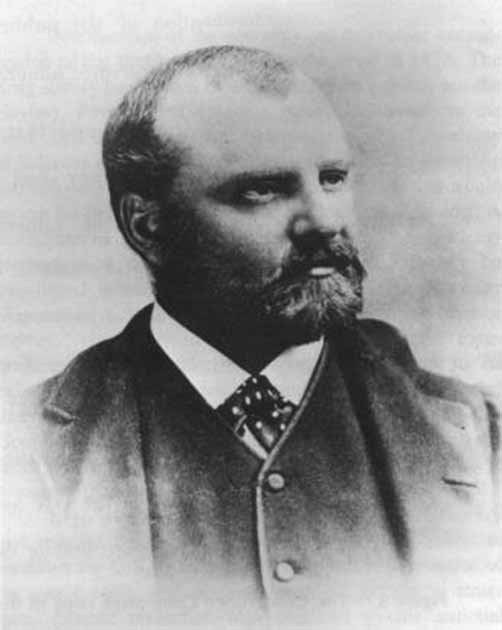

One night in 1871, two cousins and prospectors, Philip Arnold and John Slack, appear at the doorstep of George D. Roberts’ office in San Francisco. George Roberts was a financier, mining broker, and businessman described as “a man willing to move swiftly – perhaps too swiftly – when opportunities arose.”

The cousins Arnold and Slack asked Roberts if they could enter his closed office and keep something there overnight. After some pushing from Roberts, the cousins told the man that the leather bag they had was full of rough (uncut) diamonds that they found at a gem field at a secret location.

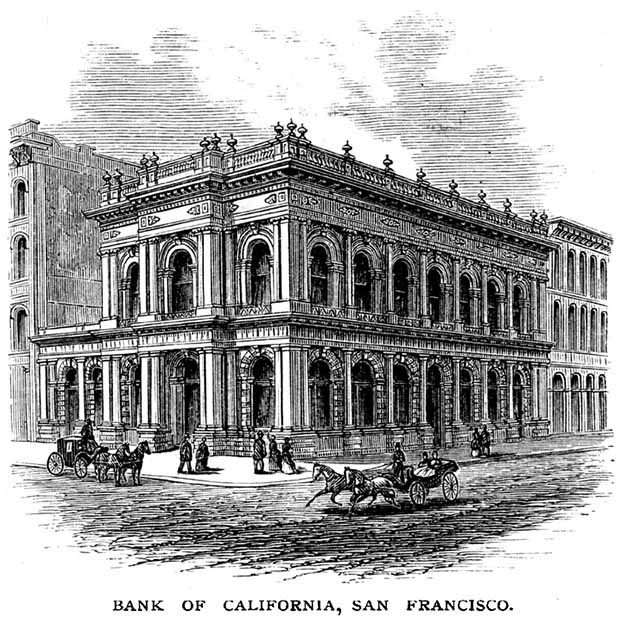

Arnold and Slack said they intended to deposit the bag at the Bank of California, but the bank was closed at that late hour. Arnold and Slack made Roberts swear that he would not speak to anyone about the diamonds.

But here is the thing about George Roberts: he was terrible at keeping secrets, and almost immediately after Arnold and Slack left the office, Roberts called William Ralston, the very wealthy founder of the Bank of California and a man named Asbury Harpending who is often described as an “adventurer and a one-time would-be Confederate swashbuckler”.

With the desire to grow their bank accounts, Ralston and Harpending agreed to provide some financial backing to facilitate more mining in the secret location. And so they set a cunning plan into motion.

Arnold and Slack knew if they wanted to catch the financial support of bigger fish, they needed to use bigger bait. This meant that the pair came back to Roberts sometime after the first visit and told the financier that they had just returned from the diamond field.

They had collected 60 pounds of diamonds and rubies with an estimated worth of over half a million dollars, a massive amount of money in the 1870s. Roberts took the bait and convinced two other wealthy mining entrepreneurs, General George Dodge and former officer in the Union Army William Lent, to join what looked like the diamond haul of the century.

Arnold and Slack convinced the financiers that they would bring back more precious gems worth millions of dollars in exchange for an investment and partial buyout of $50,000 cash. When millions of dollars of rough diamonds and other stones can be collected, a cash buyout for $50,000 seemed like a fair deal.

Roberts and the additional backers involved in this hoax didn’t know that Arnold worked for the Diamond Drill Co., a San Francisco drill maker that created diamond-headed drill bits. Industrial-grade diamonds are incredibly strong and are still used today to drill through ceramics, marble, granite, and porcelain.

The core of the drill bit contains tiny particles of raw diamonds, which are welded into the metal to give the bit strength. It is believed that the rough diamonds that Arnold and Slack had were taken from the Diamond Drill Co.

The other stones like rubies, garnets, and sapphires that the men brought back, claiming to have been found at this top-secret diamond field, most likely were purchased from Native Americans in Arizona. The ruse was working, however.

When the pair set out for their supposed third mining expedition, they didn’t go to some wind-swept rural area in the American West; they went to London. Using fake names, the con-man cousins bought an estimated $20,000 worth of rough, uncut diamonds and rubies from a gem merchant in London.

Arnold and Slack returned to San Francisco and allegedly dumped a bag with thousands of stones onto a pool table in Harpending’s home for Roberts, Ralston, Dodge, Lent, and Harpending to see. The men were dazzled by the thousands of stones, and they should have been.

All the stones Arnold and Slack presented to the men were genuine rubies, sapphires, garnets, and diamonds; however, they were low-grade and less valuable than they looked. Not all gemstones are high quality enough for use in expensive jewelry, and some are of poor quality or cut and practically worthless. This is why you can buy jewelry with someone’s birthstone for $50 or what looks like a massive stone for less than $800.

Tiffany & Co.

After looking at the heap of gemstones laying across Harpending’s pool table, the men decided that 10% of the stones from this pile were to be taken to New York for appraisal by Charles Lewis Tiffany of Tiffany and Co Jewelers. The crew of men brought the stones to Manhattan for the appraisal and were joined by Congressman and one-time presidential candidate Benjamin Butler from Massachusetts, Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune, Major General McClellan, and several unnamed “high-profile bankers”.

After examining the stones, Tiffany determined that the stones were genuine and set a value of around $150,000, which meant that the remaining 90% of stones from this most recent “trip to the diamond field” were worth about $1.5 million!

The California and New York investors created the San Francisco and New York Mining and Commercial Company. In an effort to convince people to buy shares of stock in this new company, trays full of gems were displayed in prominent jewelry shops.

The investors came to Arnold and Slack and demanded that the two men guide them to this fantastic mine, and they would bring with them Henry Janin, a well-regarded mining engineer, to assess the site further. The cousins agreed to these terms but insisted that the group be blindfolded during the final approach to their destination.

- (In Pics) Six of the Most Famous Jewels from History

- Outrageous Astronomy – Who Was Behind The Great Moon Hoax of 1835?

In June of 1872, the “inspection party” set out by train to a town called Rawlings in the southern Wyoming Territory before setting out on horseback. Knowing that the diamond field didn’t actually exist, Arnold and Slack led the group around in circles for four days and pretended to be lost. The group reached the “site,” described as a “broad mesa dominated by a cone-shaped mountain to the south.”

It took only minutes for one of the men to alert the party to a diamond he found in the dirt, which set off a domino effect of men finding diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires without much effort for over an hour. The mining engineer Janin was ecstatic and declared that the gem field was genuine.

Janin was paid $2,500 by the investors but was given thousands of shares of the company stock at around $10 per share. Once he returned to New York, Janin quickly sold all of his shares for four times their value, raking in some serious cash.

The Hoax Exposed

Arnold and Slack made moves to get as far away from San Francisco and the investors as they could, and they cashed out their stock. Slack walked away with $100,000, and Arnold received $550,000.

Together the men swindled over $650,000 from the investors, over $17 million today. Money in hand, Slack seemed to fall off the face of the earth while Arnold returned to his family in Elizabethtown, Kentucky.

The truth about the diamond field was brought to light thanks to geologist Clarence King who was working on a massive survey of agricultural and mineral resources for the U.S. government in the areas around the location of Arnold and Slack’s field. In a chance encounter, one of King’s geologists ran into Janin on a train headed to California and was shown some of the site’s diamonds, rubies, and sapphires.

The geologist reported back to King, and they both realized something wasn’t adding up. Rubies and sapphires are seldom found in the exact location as diamonds, and the geologists paid another visit to Janin in San Francisco to learn more about the miraculous find.

In October of 1872, King and a party set out to examine the Arnold-Slack site on their own, and almost immediately, the men began to find garnets, spinels, and amethysts but no diamonds. King saw a diamond several days later “perched precariously on a slender rock” and was suspicious because it would not have remained in its location for the hundreds of years needed to form a diamond.

Then the group discovered that every anthill had several holes in them besides the main entry/exit hole. These additional holes were 6-8 inches deep and looked like a stick or a cane made them, and when the hill was dug up, a gemstone was found in each one of the holes.

The site had clearly been salted, and the investors, bankers, mining engineers, and even Charles Tiffany had been fooled. It turned out that Tiffany knew next to nothing about uncut precious gems, and while Janis was tricked and his reputation tarnished, he managed to walk away with a lot of money from selling his stocks, so it wasn’t too bad for him.

Investors sued Arnold and Slack, but nothing came of it, and the two went on as if nothing had happened. The excitement of the gold and silver rush in the American West and the mining of precious gems was so enthralling that the investors and experts were oblivious to the trick being performed right before them.

Top Image: Suspicions which led to the exposing of the Great Diamond Hoax were raised when a geologist found a diamond implausibly perched on top of a rock. Source: RT Images / Adobe Stock.

By Lauren Dillon