It’s not often that legal history and ghost stories go hand in hand. But that’s exactly what happened with the Hammersmith Ghost case of 1804, a haunting chapter in British case law.

Amidst the gloomy tenements of 19th-century London, a wave of terror swept through Hammersmith as reports of a malevolent spirit gripped the community. When terror turned to hysteria an innocent man was murdered in a case of mistaken identity, leaving the British courts in a bit of a quandary.

Can a man be found guilty of trying to kill a ghost? It took them a surprisingly long time to find an answer. This real-life horror story sparked a legal saga that endured for nearly two centuries.

Haunting Hammersmith

Towards the end of 1803 the people of Hammersmith in west London began claiming they had seen or even been attacked by a ghostly apparition. The ghost was said to be of a man who had killed himself the year before and was buried in Hammersmith’s churchyard.

The belief at the time was that suicide victims had committed a mortal and were condemned to hell. Their bodies were not allowed to be buried in consecrated ground as this would stop their souls from being at rest. As such the locals believed they were being haunted because the suicide victim had been buried where he shouldn’t.

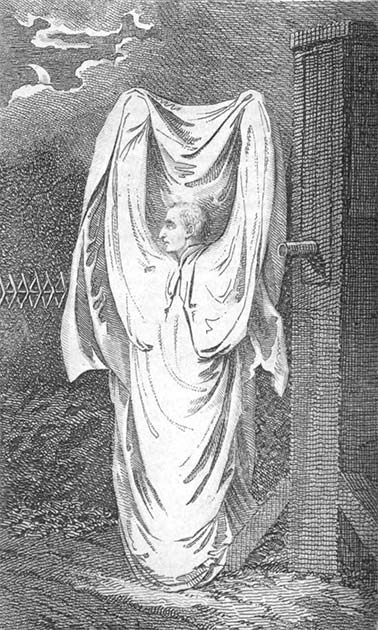

Reports of what the ghost looked like differed somewhat. Some witnesses claimed the ghost was very tall and dressed in white robes. Others said it wore calfskin clothes and had horns and large glass-like eyes.

These were incredibly superstitious times and the ghost story quickly circulated. People became increasingly paranoid as reports of people being attacked by the entity began to spread. In particular, two women, one elderly and one pregnant were said to have been attacked while walking past the local church. Supposedly it was so traumatic they both died not long after from shock.

Another report of an attack came from brewer’s servant Thomas Groom who claimed he had been attacked while walking through the churchyard at night. “Something” had pounced from behind a tombstone and grabbed him by the throat. It only ceased its attack when Groom’s companion noticed something was wrong with his friend.

The final ghost sighting before tragedy struck occurred on 29 December 1803 when a night watchman by the name of William Girdler spotted the ghost along Beaver Lane. He gave chase but the ghost managed to escape by throwing off its white shroud and disappearing. This sighting led to some citizens setting up armed patrols of the area in the hopes of catching the ghost.

Sadly, this mounting hysteria would lead to tragedy. On the night of 3 January 1804, Girdler ran into one of these armed citizens on the corner of Beaver Lane.

It was 29-year-old excise officer and wannabe ghost hunter Francis Smith. Smith was carrying a shotgun and told the watchman he was looking for the ghost. The two arranged to meet up at 11 pm, when Girdler had called the hour, to catch the ghost together.

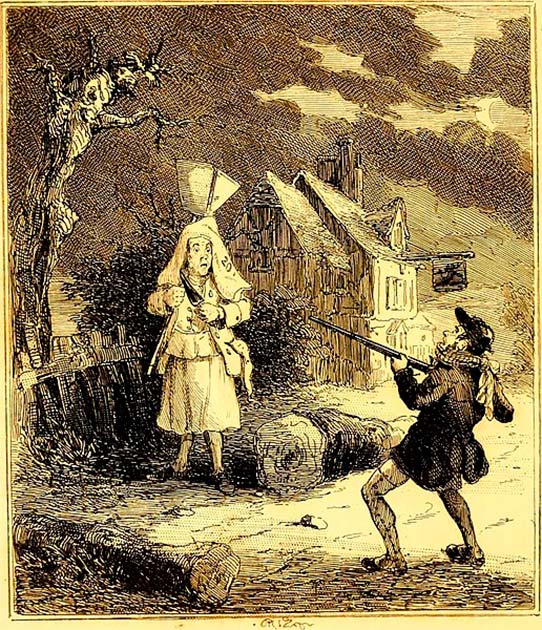

At just after 11 pm Smith ran into Thomas Millwood, a bricklayer who was heading home after paying a visit to his parents and sister. During this time bricklayers wore all white clothing and Millwood was wearing “linen trousers entirely white, washed very clean, a waistcoat of flannel, apparently new, very white, and an apron, which he wore round him”. It’s easy to guess what happened next.

According to Millwood’s sister Anne, who overheard the encounter, Smith said, “Damn you; who are you and what are you? Damn you, I’ll shoot you” before shooting Millwood in the head.

Upon hearing gunfire several neighbors ran out to see what the commotion was all about. Upon finding an agitated Smith standing over a dead body they told him to go home. Before he could do so however a constable arrived and arrested him. Millwood’s lifeless body was then carried to a nearby inn where a surgeon, Mr. Flower, later examined the body.

Mr. Flower found that the cause of death was “a gunshot wound on the left side of the lower jaw with small shot, about size No. 4, one of which had penetrated the vertebrae of the neck and injured the spinal marrow.” Smith was in a lot of trouble.

The Trial and the Law

Smith was tried for willful murder and his trial did not go well for him. It began with Millwood’s tearful widow telling the court how she had warned her husband to cover up his white clothes. He had already been mistaken for a ghost on at least one other occasion and his wife had feared for his safety.

Millwood’s sister then gave damning testimony. She recalled how even though Smith had warned her brother first, telling him to stop, he had fired almost immediately. The Chief Judge, Lord Baron Sir Archibald Macdonald, then reminded the jury that premeditation was not needed for a guilty verdict, just the intent to kill.

The judge then pointed out Millwood had never attacked Smith and was never even given the chance to provoke Smith. Furthermore, Smith had made no attempt to “catch” the ghost and had chosen to shoot on sight. As such he felt that the killing could not be deemed either an act of self-defense or an accidental shooting.

- Murderous Intent: The Cranmers and the Demon of Brownsville Road

- The (Mostly) True Story of “Ghost Photography” (Video)

Millwood’s defense brought in a number of declarations of Smith’s good character but the judge was having none of it. He told the jury that good character had nothing to do with the case, Smith had shot Millwood pure and simple. He emphasized that Millwood had done nothing wrong. And that even if he had been pretending to be a ghost that would have only been a small misdemeanor, not something to be shot over.

After an hour’s consideration, the jury came back with a verdict of manslaughter. The judge told them that their choices were either murder or acquittal and sent them away again. They then returned with a guilty verdict. Smith was sentenced to hanging and dissection. After an appeal to the king, this was commuted to a year’s hard labor.

The crux of the case came down to whether or not Smith could be held liable for his actions even if they were the result of a mistaken belief (Millwood being a ghost). At the time the judge held that the reason Smith couldn’t plead self-defense was that he had never been in any danger. He had been mistaken and had taken a man’s life, and so should pay the penalty.

But this didn’t sit right with everyone, including the king, who commuted the original sentence. Smith had made a serious mistake but was it really fair not to take that into consideration? It took 180 years for England’s legal system to decide.

A Court of Appeals decision from 1984 decided that when it comes to self-defense whether or not the accused was mistaken or not should be taken into consideration at trial. The trial’s judge, Lord Chief Justice Lane, stated that even if the mistake was an unreasonable one (like thinking someone is a ghost, or thinking a shotgun could kill a ghost for that matter) if the accused believed it at the time, then they should be allowed to rely upon it in court. The decision was later approved by the Privy Council in Beckford v The Queen (1988) and was later written into law in the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008, Section 76.

Conclusion

So, if Smith had been tried 180 years later would he have gotten away with the killing of Millwood? That’s still up for debate. Smith went out looking for trouble and he found it.

Whether or not Smith was mistaken, a completely innocent man lost his life that night because someone had an itchy trigger finger. The UK has strict rules on how much force can be used in self-defense and it’s hard to believe any modern jury would consider shooting a ghost in the head with a shotgun to be “reasonable force”.

But one question remains, who or what was the Hammersmith ghost? As it turns out the true culprit was an elderly shoemaker and prankster by the name of John Graham. All the publicity surrounding the case convinced him to come forward and confess. His apprentice had been scaring Graham’s grandchildren with ghost stories and he’d decided to teach him a lesson by dressing up as a ghost.

Top Image: The Hammersmith Ghost shooting created a legal quandary that remained unresolved for centuries. Source: Top Images / Adobe Stock.