The preeminent Egyptian port, Thonis-Heracleion, was lost at the bottom of the sea for 1300 years.

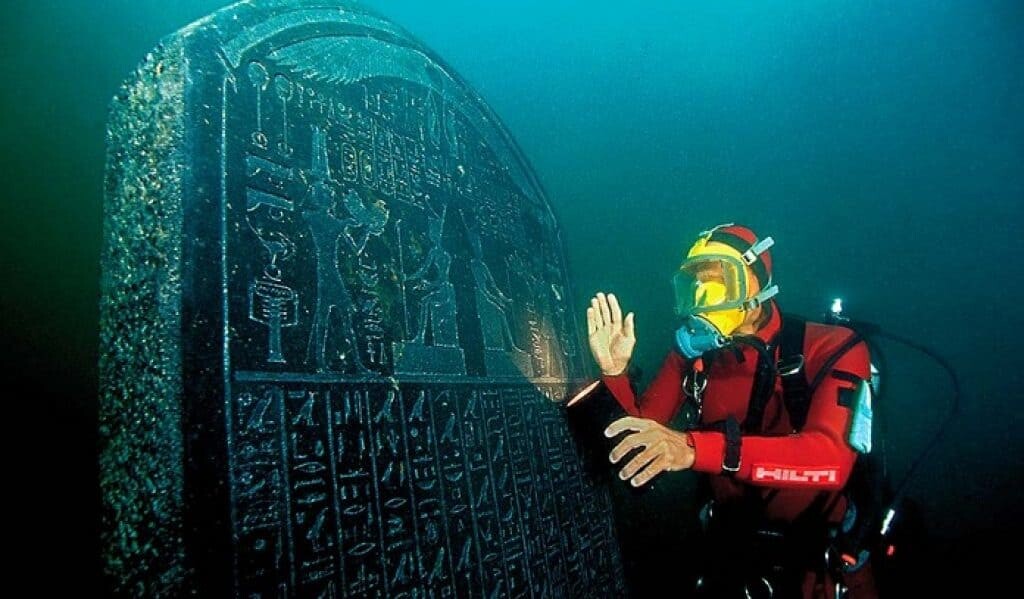

The Egyptian city of Thonis-Heracleion was the main port of entry to the Mediterranean Sea between the eighth century BCE and the fourth century BCE. By the eighth century CE, what remained of the city sank into the sea and eventually became a distant memory. Without any trace, except for a few references in historical writings, the forgotten ruins rested undisturbed until the 21st century. In 2000, the European Institute of Maritime Archaeology, led by renowned archaeologist Franck Goddio, finally discovered the city’s treasures in the depths of the Abu Qir Bay.

For thirteen years, Goddio and his team methodically excavated and explored the sunken city. They also found more than 64 shipwrecks and 700 anchors in the Abu Qir Bay. The high number of maritime relics led researchers to believe that Heracleion was a mandatory port of entry for trade between the Nile and the Mediterranean. This is also supported by the discovery of weights from Athens, which would have been used to make important measurements of goods. Never before had such weights been found among archaeological sites in Egypt.

History of Thonis-Heracleion

For more than four centuries until the foundation of Alexandria in 331 BCE, Thonis reigned supreme over the Canopic portion of the Nile River. The Greek historian Diodorus of Sicily wrote about Thonis-Heracleion in his great work, Bibliotheca historica, between 60 BCE – 30 BCE. Sometime in the fifth century BCE, Herodotus wrote that the Greek god and hero, Heracles, actually first stepped foot onto Egypt at this port city. Thus, the Greeks gave Thonis the name Heracleion and built a grand temple dedicated to him. Herodotus also said Paris and Helen of Troy visited the port city.

Religious Center of Worship

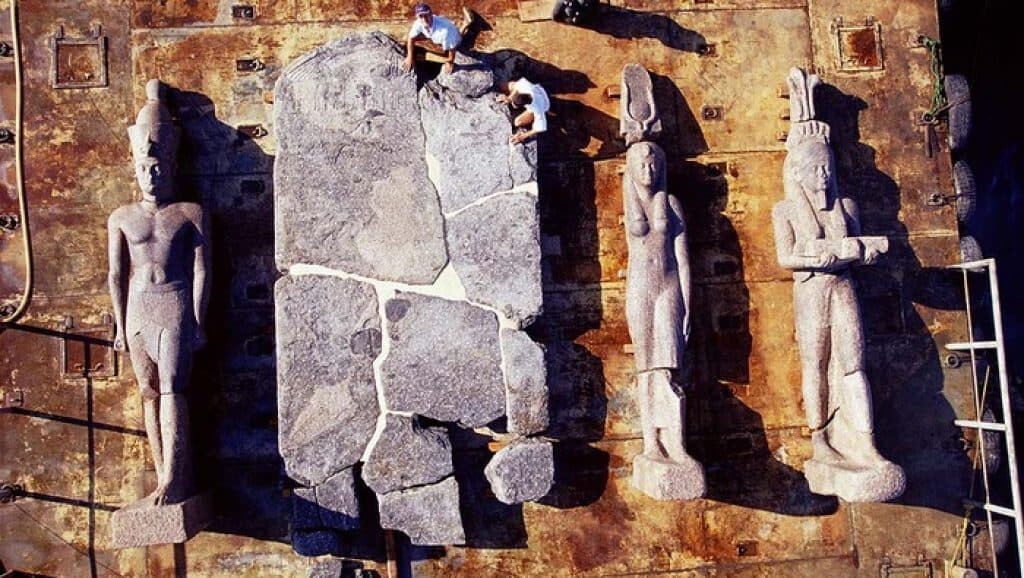

There are commonalities in the accounts of the old historians. Most significant of these is that the city boasted a huge temple constructed to honor the heroic god Heracles, hence the name, Heracleion. The city was both a bustling trade port and a religious center of worship. Sixteen-foot stone sculptures and sarcophagi believed to contain mummified animals were discovered. This reinforces the idea that this divine city was a prominent religious site. Additionally, the annual Mysteries of Osiris celebration took place at the temple. The three large statues pictured below are a pharaoh, his queen, and the god Hapy, from left to right. They stood at the entrance to the temple.

The Giant Bamiyan Buddhas of Afghanistan

The Egyptians had their own version of Heracles and, so, shared this godlike hero. Herodotus identifies Heracles with the Egyptian god Shu. Still, others claim Sesotris was the forerunner of the Greek hero. In all cases, this mythical god-hero signified strength. It seems to reflect the belief by both the Egyptians and the Greeks that they were strong, proud people, as unconquerable as the mighty Hercules himself. What better way to signify Heracleion’s strength than to essentially deem it the seat of a god? And so it was that their beloved Heracles became the focal point of the thriving port city and center of trade.

Port Business

In addition to serving as a place of worship, many official business transactions took place here. Ships from various parts of the ancient world dropped their anchors and unloaded their merchandise before returning home with a fresh supply of Egyptian goods to take back with them. Officials collected taxes and fees, and a huge amount of value traded hands. The Nile was also easily defensible from this location.

The Demise of the Temple City

Thonis-Heracleion suffered from a flaw that undermined its overall strength. The Egyptians built the city upon a portion of the Nile delta. The region was particularly susceptible to subsidence, flooding, a rising sea level, and earthquakes that had the ability to trigger enormous tidal waves. As a result, these natural circumstances waged a centuries-long battle with the port.

Beginning in the second century BCE, the splendid city started sinking into the depths of the sea. Some have theorized that flooding and the excessive weight of the city contributed to its sinking. The structures and religious statuary of which the Egyptians were so proud literally equaled millions upon millions of pounds. Additionally, the land under which those structures resided was in a perpetual state of flux due to the flooding common in the delta.

End of a City and Its Symbolism

As civilization evolved and the first millennium of the Common Era came and went, humanity approached the dawn of the Age of Reason when science and monotheism countered the age of gods and mythical heroes. It seems the sinking of this ancient Egyptian port and temple serves as a perfect metaphor for the sunset of mankind’s devotion to its old gods and reverence for ancient mythology.

You May Also Like:

Is Atlantis Really the Greek Island of Santorini?

References:

Franck Goddio

Biblical Archaeology Society

Huffington Post

Art Institute Chicago