The famous Library of Alexandria was the mythic repository of ancient knowledge. Researchers sought out copies of nearly all classical antiquity works, copied, stored, and consulted. Founded in the 3rd century BCE and destroyed sometime in the late Roman era, perhaps a million texts were cataloged and copied within the Great Library or its daughter library or warehouses. Scholars still debate whether this library ever existed, and if it did, what it contained, and when it perished.

Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE), dead for decades when the library project began, is the reason for the Great Library’s existence. He famously built his massive empire in just over a decade, from his succession to the Macedonian throne in 336 BCE to his untimely death in 323 BCE.

However, the political stability of his empire died with him. But what lived on was a cultural fusion—a mixture of eastern and western philosophy, ideology, and culture. Ptolemaic Egypt became the most powerful kingdom born of Alexander’s empire, founded by the great king’s friend and general, Ptolemy I Soter (367 BC – 282 BC).

City of Alexandria in the Ptolemaic Dynasty

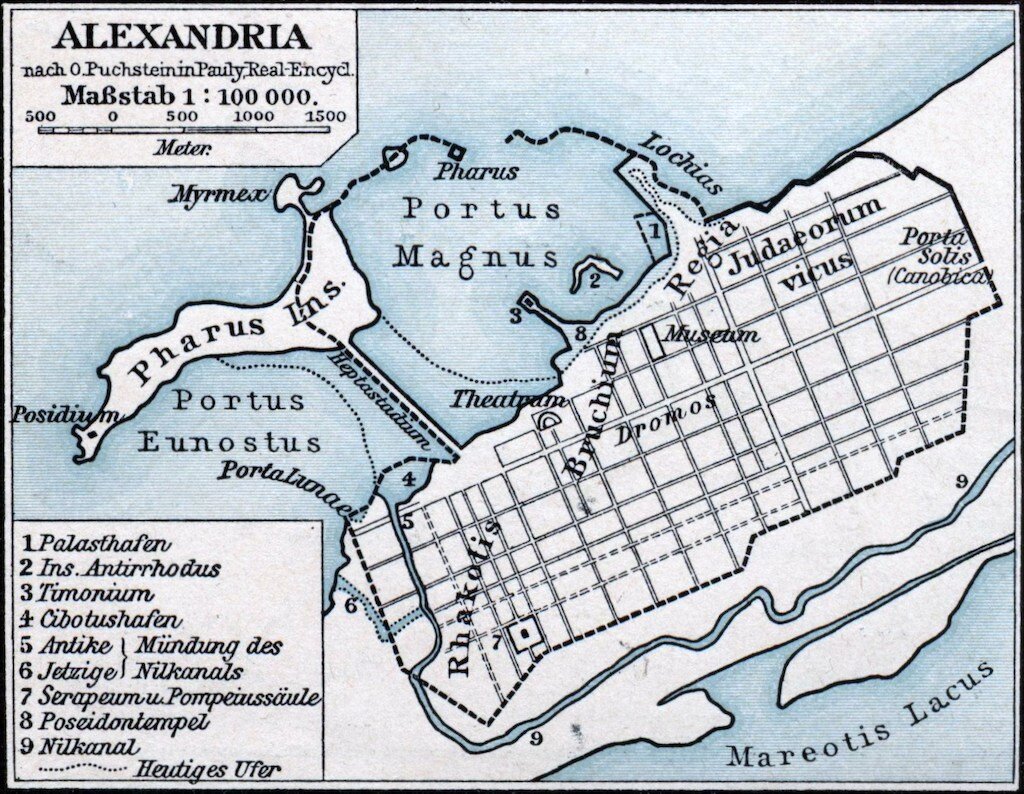

Alexander’s lasting legacy was rooted in dozens of cities that he founded, including around fifteen cities named Alexandria. None was more significant than Alexandria by Egypt, established in 330 BCE. Alexandria was a Greek enclave located west of the Nile Delta near the fishing village of Rhakotis. It was a glittering and golden new city, meant to strike awe in visitors with its fabulous wealth.

Designed by Alexander’s architect Dinocrates, Alexandria featured monumental architecture, a great harbor, the famous lighthouse of Pharos, and the Museum and Great Library, which served as the intellectual capital of the Hellenistic world. As a cosmopolis or universal polis, Alexandria was Greek in language, culture, and political orientation but global in population. Greeks co-existed alongside Egyptians, Persians, Jews, Indians, and eventually Romans.

Foundation of the Museum

The first textual evidence for the Great Library comes from the 2nd century BCE Letter of Aristeas. Some historians deem the letter is a source of apocryphal propaganda.

Surviving only in part and in later sources, the letter was purportedly written by an official at the court of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (309-246 BCE). It documents both the library’s formation and one of the most notable Greek translations to have taken place in that foundation, the Septuagint, the Greek Old Testament, a translation of the Hebrew Torah, the first five books of the Old Testament.

Later authors writing in the Roman era, Strabo and Plutarch, place the library’s origin during the reign of Ptolemy I. Plutarch wrote of the exiled Athenian Demetrius. He proposed a Museum, or temple of the Muses, and accompanying library at the court of Ptolemy I in Alexandria. Ptolemy I wanted to codify Alexander the Great’s personal diaries and histories. Demetrius’ plan offered a means to this end. By the end of his reign, Ptolemy reportedly collected upwards of 50,000 texts that cluttered the rooms of his palace and formed the core of Demetrius’ proposed repository.

Expansion

Ptolemy III Eugertes (280-222 BCE) continued work on the Great Library, vastly expanding the collections. He reportedly sent buyers across the Mediterranean to scour bookstalls, aiming to acquire copies of the entire canon of classical works. By his decree, ships ported in Alexandria were searched for scrolls to be copied or stored at the Great Library. Warehouses at the harbor provided means to return works or for distribution elsewhere.

Even before Ptolemy III expanded the collection, a second or daughter library was founded. Perhaps founded at the Temple of Serapis, to accommodate the ever-growing collection.

The Great Library of Alexandria

Personal libraries were common in the ancient world, but public libraries, particularly at the purported scale of Alexandria’s, were an innovation. Something akin to a university, the Museum and Library at Alexandria served as a home for books and scholars. The Greek geographer Strabo, in the 2nd century CE, described the Museum and Library complex as “part of the palaces, possessing a peripatos [a walkway, perhaps covered] and exedra [circular platforms with benches for discussion], and large oikos [house]…”

As a reference library, Alexandria was reportedly unparalleled. King Eumenes II of Pergamum (197-159 BCE), a rival kingdom, competed to accumulate a collection of 200,000 texts, but Alexandria dwarfed his library. Estimates for the collection size of the Great Library of the Ptolemies vary enormously, from 40,000 scrolls to 1,000,000 texts.

Scrolls, rather than books, were the typical format for texts. Multiple papyrus rolls could comprise one book or volume, which may account for this statistical disparity.

The Librarian

Alexandria’s greatest librarian was the poet Callimachus of Cyrene (310-240 BCE). For instance, he innovated a cataloging system, comprising 120 separate volumes, documenting eight categories of texts held in Alexandria. The catalogs, what Callimachus called the Pinakes, or Lists, included biographical and bibliographical detail on each source.

His work was thought to include references to all known works of classical literature to his day. Additionally, he organized the library’s holdings by category, including dramatists, rhetoricians, orators, historians, philosophers, legislators, poets, and miscellaneous works. The physical texts were organized in the library, first by category and then alphabetically, by each title’s first letter.

The Collection

Natural philosophers, engineers, mathematicians, and others would have stayed at the library when working in Alexandria. More than an attraction for bibliophiles, the library was an active community of scholars.

One academic, Timon of Philus, rejected from a residency at the library, bitterly addressed the community of scholars as “endowed scribblers.”

In addition to the classical works of Hesiod, Homer, Euripedes, Aeschylus, Plato, and Aristotle, contemporary poets and authors worked at Alexandria, including Apollonius of Rhodes and Theocritus of Syracuse.

The Ptolemies were patrons of the sciences, particularly favoring the works of mathematicians and astronomers such as Archimedes, Euclid, Eratosthenes, and Aristarchus of Samos.

Many Destructions of the Great Library

The Great Library suffered a series of accidents or deliberate phases of destruction. It is impossible to reconstruct what texts are lost and when it happened. Portions of the Great Library, the daughter Library at the Serapeum, or scrolls held at the warehouse may have suffered destruction during different periods. Later, Roman authors refer to works of the playwright Meander, Varro’s Antiquities, and portions of Livy’s History of Rome that may have been consulted in Alexandria and are lost today.

Julius Caesar and the First Destruction

Julius Caesar is often blamed for the first fire at the library. Following his victory at the battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE, Julius Caesar pursued his defeated rival, Pompeius Magnus, to Egypt.

Caesar arrived in Alexandria as a civil war raged between young king Ptolemy XIII (62-47 BCE) and his older sister Cleopatra VII (69-30 BCE). While in Egypt, Ptolemy XIII’s forces besieged Caesar and his troops at the harbor in Alexandria. Caesar instructed his men to set fire to the Ptolemy XIII’s fleet. But the summer winds spread the flames from the port into the warehouses and perhaps even into the city.

Plutarch tells us in his 2nd century CE Life of Caesar of the burning of a portion of the library’s holdings, likely dock-side warehouses but possibly the Great Library itself. Historians question whether this fire, if it occurred, was accidental at all, or a deliberate and pointed act by Caesar to eliminate the library.

Library in the Late Roman Empire

Several other episodes of the destruction of the Museum and Library are hypothesized in Late Antiquity or the later Roman Empire. From the late Roman emperors to the 7th century Caliph Omar, both the city of Alexandria and the library could prove dangerous. As the intellectual capital of Egypt, Alexandria boasted a well-informed and wealthy populace. As Rome shifted from a pagan to a Christian empire, Alexandria became even more dangerous as a source of knowledge that contradicted the new faith.

During the third century, the Roman Empire became torn apart by internal and external pressures. The third-century chaos saw the empire’s division into as many as five parts. The empire only became mended with the reign of Diocletian (284-305 CE). Both Diocletian and his predecessor Aurelian (270-275 CE) oversaw conflagration and revolt in Alexandria. This may have resulted in losses at the Great Library.

Spread of Christianity

By the reign of Emperor Theodosius I (378-395 CE), Rome entered a new era, Late Antiquity. Christianity had taken firm root in what remained of the empire by the fourth century. Moreover, Christianity left classical or “pagan” philosophies relegated to a shrinking population of intellectuals. Paganism as a living religion became outlawed in 391 CE. In fact, religious paganism became affiliated with simple countryfolk – the pagani (people of the pagus). The last great pagan philosophers, including many Neoplatonists, maintained their beliefs in the shadows. The new Christian Empire deemed learning of the classical past as less valuable.

You May Also Like: Hypatia of Alexandria: A Classical Age Female Scholar

In an age of Christian victory, the Library became a repository of knowledge secondary to the more critical factors of faith. In 391 CE, a riot in Alexandria centered on the Temple of Serapis, the Serapeum, may have led to the conflagration of both the daughter Library and the Great Library itself. One of Alexandria’s most famous Neoplatonist philosophers Hypatia is often associated with the library and its destruction. However, her death in 415 CE occurred decades after the assumed final destruction.

Alexandria today

Sunken secrets of ancient Egypt are routinely discovered in the Mediterranean Sea. For instance, underwater archaeologists continue to reveal statues, sculptures, and architectural columns and blocks from the old city and harbor.

The 2002 construction of a new library in Alexandria is a “spiritual successor” of the ancient and original facility. While gone, the Great Library of ancient Alexandria remains a lost intellectual wonder of the world and inspiration for new generations.

References:

Roger S. Bagnall, “Alexandria: Library of Dreams,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 146, No. 4 (Dec., 2002), pp. 348-362.

Lionel Casson, Libraries in the Ancient World (Yale University Press, 2001).

Andrew Erskine, “Culture and Power in Ptolemaic Egypt: The Museum and Library of Alexandria,” Greece & Rome, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Apr., 1995), pp. 38-48.

S. Johnstone, “A New History of Libraries and Books in the Hellenistic Period,” Classical Antiquity, Volume 33 (October 2014): 347-393

Justin Pollard and Howard Reid, The Rise and Fall of Alexandria: Birthplace of the Modern World (Penguin, 2006)