In 1956, the movie The King And I, starring Deborah Kerr and Yul Brynner was nominated for nine Oscars, winning five. The film was based on a Broadway musical, itself an adaptation of a best-selling novel by Margaret Landon.But the novel itself purported to be based on a true account of the experiences of Anna Leonowens and the King of Siam. The story of “Anna and the King” has been made into a movie at least four times (and is being adapted again).

With so many layers of interpretations and adaptations, some of the original truth of the story must have been lost. But the tale is certainly a captivating one, and to find out why it is so appealing to audiences, we need to turn to the source: the account of the real-life Anna.

Early Life And Early Lies

The Anna on which different stories and movies are based was Anna Harriette Leonowens, born Ann Harriet Emma Edwards. She was born to Thomas Edwards and Mary Ann Glascott in Ahmednagar, in the Bombay Presidency in India, on the 5th of November, 1831. Her father was a Sergeant in the British regiment stationed there.

Even at this early stage, the truth becomes elusive. Later, Anna would claim that she was born in Wales in 1834, styling herself as both younger and from somewhere closer to the center of the Empire. She also claimed that her surname was “Crawford” and her father was a Captain. But all such accounts about her personal life were demonstrably false.

Anna lost her father at a very young age and was just a tiny baby when her mother became a widow. Her mother was left alone with two little daughters. Soon after her father’s death, Anna’s mother remarried an Irish Catholic corporal (later demoted further to private) named Patrick Donohoe.

The family was forced to relocate to posts in Western India on a continuous basis following the regiment of Anna’s stepfather. In 1841, the family finally settled in Deesa, Gujarat.

Anna went to the Bombay Education Society’s girls school located in Byculla, a neighborhood in Mumbai. It was a school that provided admission to the children of mixed-race whose military fathers were absent or dead.

Again, we see Anna’s attempts to improve her social position by fictionalizing her past. Anna was depicted as being sent to the English boarding school in the stories and movies, whereas she actually went to a school meant for children of British soldiers. In a world where hierarchy was everything, Anna’s attempts to dress up her past are of course understandable.

Anna’s relationship with her stepfather wasn’t a happy one, and researchers believe that Donohoe was known to be an ill-tempered man. Moreover, he was accused of abusing his stepdaughters and attempting to force them into marriages to much older men.

In 1847, Donohoe became an assistant supervisor and relocated to Aden. However, whether the whole family relocated with him or stayed in India is still unknown. Records show that by this point Anna had cut off all ties with her family and chose not to be associated with them in any manner.

Marriage and Widowhood

At the young age of seventeen, Anna fell in love with Thomas Leon Owens, an Irish Protestant seven years older than her who had relocated to India in 1843. Anna’s stepfather and mother objected to the relationship as the suitor was merely a private at the time, having been temporarily downgraded from sergeant for some unspecified offense.

However, despite all opposition, Anna Edwards married Thomas Leon Owens in the Anglican Church in Poona on Christmas day in 1849, a month after her 18th birthday. In the marriage certificate, the middle and last names of Thomas were merged, and the result was “Leonowens.” Anna always claimed that her stepfather was completely against her marriage, although his signature appears on their marriage document.

In December 1850, Anna and her husband, Thomas, had their first daughter. However, unfortunately, the little girl died when she was just seventeen months old. Shortly after in 1852, Anna and Thomas went to Perth in Australia along with her uncle W. V. Glasscott, where they spent a number of years.

Thomas worked initially as a clerk when they moved to Australia, holding a number of other jobs there before they moved again to Penang in Malaysia. There Thomas worked as a hotel keeper. Anna and Thomas had four children together during this time, two of them survived infancy. One was their daughter named Avis, and another a son called Louis.

Unfortunately, Thomas died an untimely death in 1859 due to a stroke. He was buried in the Protestant Cemetery of Penang on the 7th of May, 1859, leaving Anna as a widow. After the death of her husband, Anna went back to Singapore and tried creating a new identity, styling herself as being a Welsh-born lady and the widow of a British Army Major.

In order to support her two children, Anna Leonowens started teaching and soon opened a school in Singapore for the children of British officers. It is here that she started reinventing her life again. The school did not achieve financial success, but it helped Anna to earn a reputation as an educator, and the connections she made here helped her secure a position in the royal court of Siam (Thailand).

A Teacher In The Royal Court

Mongkut, the King of Siam, was keen to secure a suitably “English” education for his wives, concubines, and children. However, he wanted an educator who would teach them without making any efforts to convert them into Christianity. Before becoming a king, Mongkut had been a Buddhist monk for about 29 years.

In 1862, Anna Leonowens was offered the post by Tan Kim Chang, the consul in Singapore, and decided to teach the children and wives of the King of Siam. While in the fictional works, it is depicted that Anna was hired as a governess by the King of Siam, she was actually merely an English teacher.

Anna sent her daughter to a boarding school in England, taking only her son with her to Bangkok. As a teacher in the Siamese court, she succeeded Dan Beach Bradley, an American missionary. As a woman and of English stock, she would have brought a very different flavor to the court than her predecessor.

Anna spent about six years in the Siamese court, until 1867. At first, she was an English teacher for the wives and children of the King of Siam. However, later she also worked as the language secretary for the King. In this position, she enjoyed great respect and had a high degree of political influence.

However, the terms and conditions of employment were not satisfactory for her. Even though she had a position of some status in the court of the King, she was not invited to be a part of the social circle of the British traders and merchants of that area.

In 1867, Anna Leonowens went to England on leave due to health issues. When she was in England, the King, as well as his son, Prince Chulalongkorn, fell ill due to malaria. While the prince recovered, the King died in 1868.

In his will, the King had mentioned Anna Leonowens and her son. However, they did not receive any legacy. Anna tried communicating with the prince, who had succeeded his father, to negotiate about her return. The new King corresponded with her in a very amicable manner for a number of years, but never invited her to return to his court.

A Move Into Literature

When Anna Loenowens was unable to return to the court of the King and pursue her career, she looked for other options in order to support her children and herself. After a period of three years, she wrote the memoirs.

- Angkor Wat: The Enduring Pride of the Khmer Empire

- Who was Dina Sanichar, The Real-Life Mowgli Raised by Wolves?

The first one, “The English Governess in Siamese Court,” was published in 1870. This was followed by a more racy venture, “The Romance of the Harem” written by Anna in 1873. Both books were bestsellers, and gained Anna a lot of popularity.

However, the family of King Mongkut did not like the manner in which Anna had portrayed the King. The title of the memoir was considered to be inaccurate as she was not a governess at the court. Her task was not to care for and educate the royal children but to teach English to the wives and children of the King.

According to Abbot Low Moffat, the biographer of Mongkut, the accounts of Anna Leonowens relating to her life at the Siamese court were very exaggerated. Anna, in her books, had portrayed the King as a lecherous and unkind man. She wrote that he chose to preserve a number of customs such as sexual slavery and prostration.

However, as a matter of fact, King Mongkut was known to be a progressive and kind man in Siam. The King had been a Buddhist monk for years, and these facts completely contradicted his character.

In Anna’s second book and Margaret Landon’s novel, a concubine named Tuptim is accused of adultery with the Buddhist monk. It was written that the concubine was tortured in the palace. However, this story was most probably based on unsubstantiated court gossip that happened even before Anna was there. In reality, Tuptim was one of the wives of Prince Chulalongkorn and not King Mongkut.

Responding to the accounts of Anna Leonowens on the Siamese Court, the new King Chulalongkorn said that “she has supplied by her invention that which is deficient in her memory.” Many years later, when King Chulalongkorn saw Anna in England again, he asked her why she had portrayed his father in such a negative way. However, he could not find an appropriate answer to his question.

But what of the great romance between Anna and the King that has captivated moviegoers for almost a century? This is certainly the central narrative in a number of the literary works and films. However, there was no such relationship between them. There was mutual respect, but nothing more.

Anna’s Son

Louis Leonowens, however, remained in Siam. In the movies, it is shown that Louis died. However, in reality, he grew up and was educated along with the children in the Siamese court.

After returning to Europe to complete his education, he was offered a position in the Royal Cavalry. In 1905, he started his own business, and this company survives to this day, still known by his own name.

If you have seen the movies on Anna and the King or read the novels, you might feel that Anna Leonowens was very much influenced by the royal Siamese Court. Well, it is quite natural for anyone to think so on the basis of the depictions made in the novel and movie. However, in reality things were quite different.

Were there reasons other than the obvious for Anna to fictionalize her time in Siam? Some researchers believe that she was a feminist, and portrayed King Mongkut in such a way due to the cruelty she had to suffer because of her stepfather. Irrespective of the reason, it is quite clear that while some of the parts of the novels and movies on Anna are true, a number of facts are just fictional.

On the basis of research and findings, it can be said that Anna exaggerated the facts that she really saw through her eyes. These accounts were then subject to further interpretation, and the story that caught the public imagination to this day never happened.

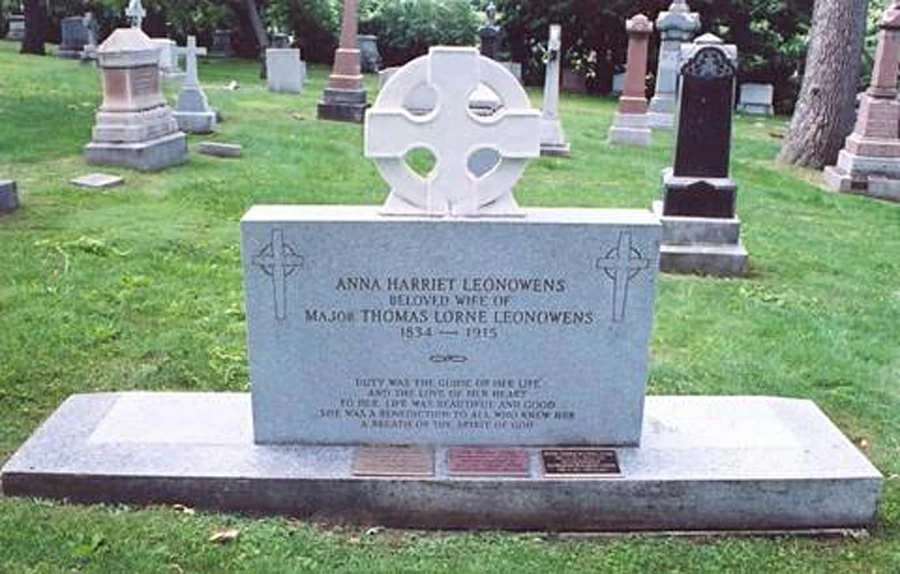

Top Image: Anna Leonowens / Scene from The King and I. Source: Susanlenox / Public Domain; Unknown Author / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri